In early October 2018, Hurricane Walaka formed quickly and headed straight toward French Frigate Shoals, an atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. This atoll is made up of several tiny islets, some of which are highly dynamic and come and go (awash) each season. Five of the islets, however—East, Tern, Trig, Gin, and Little Gin—are generally static. They are also the nesting locations for 96 percent of Hawaiian green sea turtles.

The path of Hurricane Walaka and proximity to French Frigate Shoals, the nesting location for 96% of Hawaiian green sea turtles. Image: The Weather Network.

The hurricane hit with category 5 winds, washing away almost all 11 acres of East Island, where more than half of these turtles nest. Females had finished laying eggs for the 2018 season, but 19 percent of the nests laid on East Island were lost. Trig Island also went awash earlier that year, leaving only Tern and the Gin Islands for suitable sea turtle nesting habitat.

Map of French Frigate Shoals atoll. The red Xs are over islands that have completely eroded away from different causes between 1990 and 2018 and have not yet reappeared (based on our most recent observations). The yellow Xs represent islands that are naturally highly dynamic and come and go (awash) each season.

The Plan to Find a Fertile Turtle

Reproductive biologist Dr. Camryn Allen watches a green sea turtle hatchling crawl to the ocean shoreline on East Island just weeks before Walaka hit French Frigate Shoals as a category 5 hurricane. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Lindsey Bull.

With so many turtles using East Island for nesting, and the island now gone, researchers from NOAA’s Marine Turtle Biology and Assessment Program were curious where females would lay their eggs. Dr. Camryn Allen, the team’s reproductive biologist, had an idea: “We should ultrasound the females to find one that will mate/nest during the next season,” she said, “then we can place a tracking device on her, and see where she goes to nest.”

Generally, female Hawaiian green sea turtles only reproduce every four years, so there was no guarantee of finding a good candidate even with the aid of an ultrasound. The team had never done this within Hawai‘i before. Based on research from scientists who had, they knew there was only an 11 percent chance of finding a female that was reproductively active, but that small chance still gave them hope. Information about the migration of females to French Frigate Shoals would be valuable, especially after the loss of East Island.

On March 4th, after 2 months of preparations, the team traveled to the North Shore of O‘ahu in search of adult-sized female turtles. If they found one, they would perform an ultrasound to see if she was “gravid,” or ready to breed that season. At the start of the reproductive season, gravid adult female green sea turtles are found around the main Hawaiian Islands before they migrate to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to nest, so the team only had 2–3 months to find a candidate.

The team found three adult females and performed ultrasounds of their ovaries to look for follicles filled with yolk, which would indicate that a female is gravid. This was the first time the program used an ultrasound in the Pacific Islands region. Even though they did not find a gravid female that day, it was considered a successful test.

Dr. Alexander Gaos and Marylou Staman watch as Dr. Camryn Allen performs an ultrasound on an adult female green sea turtle on the North Shore of O‘ahu. If they found follicles filled with yolk, they would attach a satellite tag that could provide valuable information about the migration of gravid females from the main Hawaiian Islands to French Frigate Shoals. Photo: NOAA Fisheries.

The Mother Lode

The following Friday, March 15th, Camryn headed back to the North Shore. Two team members, Jan Willem Staman and Lindsey Bull, and wildlife veterinarian Dr. Michelle Barbieri joined her. Upon arrival at a beach where turtles are known to bask in the sun, Camryn grew excited. “We hit the mother lode!” she said to Michelle. “There are already five turtles up on the beach, and one of them is an adult female!”

The team had their eyes on the adult female, but they were also interested in obtaining data from other turtles. The team had to strategically work without flushing her back into the ocean. They positioned themselves away from and behind the adult female to measure and identify an immature turtle, OA45. While they were working, an even more robust adult female of large size and healthy body condition hauled herself onto the beach.

Jan Willem Staman, Dr. Michelle Barbieri, and Lindsey Bull measure and identify an immature turtle, OA45, away from and behind an adult female (middle of the photo, hind end toward camera) to avoid flushing her back into the ocean. During their work, a more robust adult female hauled herself out of the water and onto the beach (large turtle in the background, facing right). Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Camryn Allen.

The team didn’t want the most promising turtle to evade them, so they shifted their plan to ultrasound the newcomer next. Much to their delight, the ultrasound showed that this robust female was indeed gravid—the follicles in her ovaries were filled with yolk!

Ultrasound of four ovarian follicles filled with yolk from a gravid adult female green sea turtle (OA48) observed on O‘ahu’s North Shore. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Camryn Allen.

Dr. Michelle Barbieri and Lindsey Bull perform a happy dance after discovering a gravid female green sea turtle on O‘ahu's North Shore. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Camryn Allen.

Lindsey Bull and Jan Willem Staman place a purpose-built box around the female green turtle to enable the team to apply a GPS satellite transmitter. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Camryn Allen.

Michelle and Lindsey proceeded to measure the length of her shell and collect samples for genetic and hormone analysis. They looked for previously applied permanent identification tags that might tell us more about her history, and applied the tag “OA48” to her shell in white non-toxic paint. The team also applied a GPS satellite transmitter to monitor her migration to her nesting ground.

The identifier "OA48" was etched into the turtle's shell, and non-toxic paint was applied. The paint will wear off of the outer shell and remain in the etched markings for easy identification later in the season. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Michelle Barbieri.

Interestingly, Michelle and Lindsey did discover a permanent identification tag (microchip) on OA48. Searching the microchip number in the database gave them some information about her life history. She was first encountered in 1993, when she was found stuck in a silt pond with leech eggs on her body, leeches in her mouth, and tumors on her right front flipper. At that time, she was in poor condition, so it was great to see her doing so well now.

In 1993, OA48’s shell was 34.9 inches long. Since then, she has grown less than a quarter of an inch in length and less than half an inch in width, suggesting that she was a mature female in 1993. Sea turtles reach sexual maturity in Hawai‘i between 23 and 38 years. OA48 must have been at least 23 years old in 1993, so she is likely at least 49 years old today. That may sound old, but the oldest known nesting female in Hawai‘i is 61.

As they released OA48 and she made her way to the water, the team pondered what they should nickname her. “I like the name Motherload because you said we hit the mother lode at the beginning of the day,” Michelle said. Camryn agreed, “She is loaded with yolked-up follicles, so the name is fitting.”

OA48, nicknamed "Motherload," makes her way back to the water on O‘ahu's North Shore. She is now outfitted with a satellite transmitter. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Camryn Allen.

Motherload's Journey

Motherload’s satellite tag allowed the team to watch her movements from the Science Center in Honolulu. Camryn was patiently checking on Motherload’s status, and on Thursday, March 28th, she saw something new. She jumped up and ran to the office of Dr. T. Todd Jones—the leader of the Marine Turtle Biology and Assessment Program—announcing, “Motherload left! We did it!”

Motherload departed the North Shore of O‘ahu and had already passed Kaua‘i just 2 weeks after they tagged her. Their timing could hardly have been better.

Camryn taped maps of Motherload’s location to her office door for her colleagues to follow her journey. “She’s ~28 nautical miles away from French Frigate Shoals!” Camryn announced on April 6th.

But only nine days later, Camryn logged in to her computer to find a new development: Motherload had passed French Frigate Shoals. She was about 60 miles southwest of the atoll, apparently continuing west. “The next [known] nesting beach is about 200 miles farther—at Laysan Island,” Camryn said, “so we will have to see what she does over the next few days.” T. Todd explained, “she may tack back to get her bearings.”

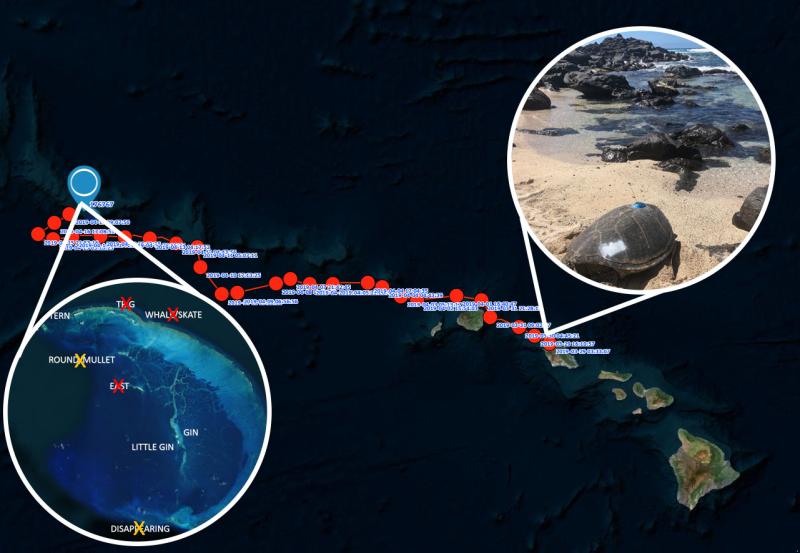

Satellite track of OA48, Motherload, showing her southwest of French Frigate Shoals by approximately 60 miles, apparently heading west.

The team waited with bated breath, but not for long—the following day, April 16th, Motherload’s track showed that she had turned, just as T. Todd predicted, and was heading for French Frigate Shoals.

Satellite track showing Motherload turning back towards French Frigate Shoals.

Motherload arrived at French Frigate Shoals on Wednesday, April 17th. Between her departure from O‘ahu and her arrival at the atoll, she swam nearly 620 miles in 2½ weeks.

The satellite track of Motherload's journey of more than 600 miles from O‘ahu to French Frigate Shoals.

Now, staff wait patiently to see what Motherload will do. To fertilize her eggs, she will need a mate. Then, she will lay her eggs in “clutches” every 2 weeks, laying three or four nests.

But where will she lay them?

As of April 25th, Motherload has spent much of her time around Tern Island—a World War II-era runway surrounded in part by the original seawall and building structures. Motherload has also scoped out the prior location of Trig Island, and the team wonders if she will check-in on the Gins and the reformation of East.

Satellite track of Motherload's activity at Tern Island (left side) and the former location of Trig Island (upper right) at French Frigate Shoals in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.