During the summers of 2017 and 2018, the International Whaling Commission’s Pacific Ocean Whale and Ecosystem Research (IWC-POWER) cruises systematically surveyed remote Alaska waters. Scientists led by Koji Matsuoka of Japan’s Institute of Cetacean Research used a combination of passive acoustics and visual surveying to detect and locate right whales. Over the two summers, the team photographed and identified a total of 15 individual North Pacific right whales. At least four of these were documented for the first time, and one was determined to be a juvenile.

“Through these collaborative studies, we found 15 unique whales. In a population numbering in the dozens, that is remarkable,” said Crance. “But discovering the juvenile was the best news. It’s the biggest sign of hope we have that there is at least one female still reproducing out there— that this population may yet have the ability to recover.”

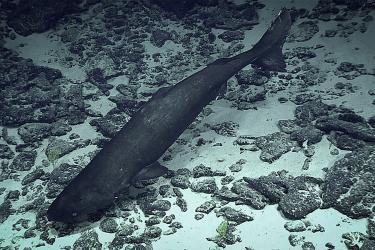

Hunting for the Right Whale

Right whales once ranged across the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska in abundance. But whalers gave them their name for a reason: right whales are slow, rich in oil, and they float when killed. They were the “right” whales to hunt.

Extensive whaling in the early 19th and 20th centuries decimated the North Pacific right whale population. After whaling ended, the population began to recover. Then, during the 1960s, illegal Soviet whaling took more than 770 whales, bringing them to the brink of extinction. In 1970, the North Pacific right whale was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

The population still has not recovered. Today, the North Pacific right whale is divided into two populations: eastern and western. The eastern North Pacific population is estimated to number around 31 individuals. With a high ratio of males to females, only about 10 females are thought to exist.

Searching for Knowledge

To help protect the remaining population, in 2006, NOAA established federally designated critical habitat in the southeastern Bering Sea and northern Gulf of Alaska. Alaska Fisheries Science Center surveys in the eastern Bering Sea have shown that North Pacific right whales are commonly found in the critical habitat during summer months. However, little is known about their range outside of this region and season.

“Their migration routes and breeding sites remain unknown. We don’t know if the population is stable, increasing, or decreasing,” Crance said.

The remote habitat and extreme rarity of these whales makes collecting this vital information a challenge.

“With so few animals in a vast ocean, the greatest difficulty always lies in just finding them. There have been many surveys where we have heard them, but didn’t see them. There are so many other large whales out there. In the Gulf of Alaska, for instance, most right whale acoustic detections have been in Barnabas Trough, in the middle of humpback soup. It isn’t easy to spot the one right whale among 50 humpbacks.”

To effectively conserve and recover eastern North Pacific right whales, scientists need to know more about them. But first they need to find them.

The Power of Collaboration

The IWC-POWER program is an international effort to collect information on the population status of large whales in North Pacific waters. This information will allow scientists to assess the need for and effectiveness of conservation and management actions. Collaboration is fundamental to the success of the program.

IWC-POWER cruises have systematically surveyed the North Pacific every summer since 2010. The 2017–2018 cruises were conducted in known North Pacific right whale habitat. To aid in detecting and locating right whales, we used passive acoustics using sonobuoys (instruments that listen underwater) for the first time on these cruises. Crance joined the team as an acoustician.

While the ship steamed along the predetermined survey tracklines, the visual team watched while Crance listened. Crew visually scanned for whales from the crow’s nest and flying bridge. To listen for whales, Crance deployed sonobuoys. Sonobuoys are free-floating, expendable passive acoustic devices that transmit audio signals in real time to a receiver on the ship. If right whale vocalizations were detected, multiple sonobuoys were deployed simultaneously to zero in on the calling animal’s location.

When whales were detected, the ship broke from the trackline to attempt to sight the animal. Once whales were spotted, the team photographed them for identification. Photos would later be cross-referenced against the Alaska Fisheries Science Center Marine Mammal Laboratory catalog of known individuals. Scientists also collected skin and blubber biopsy samples from six whales to determine their sex.

“These surveys are very successful at finding marine mammals,” Crance said. “Combining their skill at spotting whales with our acoustics was a match made in heaven.”

"The internationally collaborative POWER cruises have allowed us to survey in areas that are historically poorly studied,” said Masuoka. “The results obtained from these surveys have provided invaluable information that has greatly added to our knowledge on right whales."

Key Findings

The team sighted a total of 15 individual North Pacific right whales during the 2017 and 2018 cruises. Twelve of these were sighted during the 2017 cruise—the largest number of North Pacific right whales seen in one survey since 2004.

New Identifications

Nine of these whales were matched to known whales from the catalog. Four of the six unmatched animals were confirmed as new individuals. The 2017–18 surveys increased the number of known North Pacific right whales from 22 to 26.

A New Whale

One of the new individuals from 2017 was identified as a juvenile, estimated to be between 1.5 and 4 years old.

“Finding a juvenile was the most exciting part of this research,” said Crance. “We named him Phoenix both in homage to my hometown—and as a symbol of hope that his population may yet recover.”

A Far Northern Sighting

One right whale was sighted just south of St. Lawrence Island in the northern Bering Sea.

"We had reports from Alaska Native hunters of right whales in the area, but this was (at the time) the farthest north sighting documented with images,” Crance said.

Sex Ratio Data

Biopsy samples revealed the sex of six whales: five males (including the juvenile) and one female.

”These findings suggest that the male to female ratio is even more male-biased than we thought,” Crance said.

First Song Recording

During the 2017 cruise, Crance documented the singing of two eastern North Pacific right whales. This marked the first time anyone had recorded right whale song.

Until then, right whales were thought to limit vocalizations to individual calls, rather than the patterned phrasing that makes a song. This was well documented for Southern and North Atlantic right whales.

“We hope that documenting right whale song will have a big impact on acoustic research,” Crance said. “These songs are composed almost entirely of gunshots, and are extremely unique. If these songs are detected outside the Bering Sea, that is clear evidence of a North Pacific right whale. These detections could help determine migration patterns, or other unknown areas that are important to North Pacific right whales.”

Right Whales in the Future

These findings provide valuable information on the status and dynamics of this endangered and at risk of extinction population.

“For a population numbering in the 10s, sighting 12 individuals—including a juvenile— during one summer is cause for optimism,” Crance said. “This new information helps us better understand and manage this population, which will help give this population their best chance at recovering.”

This research was a cooperative effort between the Institute of Cetacean Research, Tokyo, Japan (Koji Masuoka); NOAA Fisheries, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Marine Mammal Laboratory, Seattle, WA (Jessica Crance); Marine Mammal Biologist, Independent Consultant, London, United Kingdom (Jessica K.D. Taylor); Kyodo Senpaku, Co. LTD. Tokyo, Japan (Isamu Yoshimura); Center for Coastal Studies, Provincetown, Massachusetts, USA (Amy James); National Marine Diversity Institute of Korea, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea (Yong-Rock An).