Killer Whale

Killer Whale

Orcinus orca

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Pod of killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Pod of killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Pod of killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Pod of killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Pod of killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Pod of killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

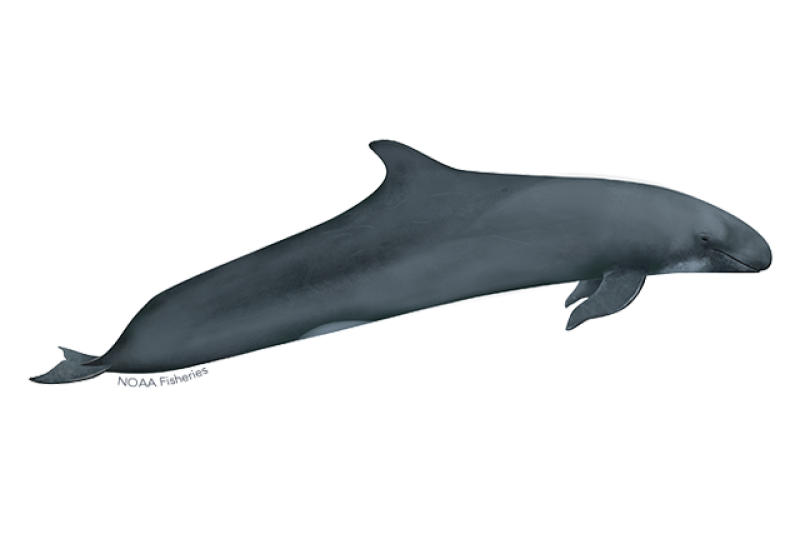

The killer whale, also known as orca, is the ocean’s top predator. It is the largest member of the Delphinidae family, or dolphins. Members of this family include all dolphin species, as well as other larger species, such as long-finned pilot whales and short-finned pilot whales, whose common names also contain "whale" instead of "dolphin."

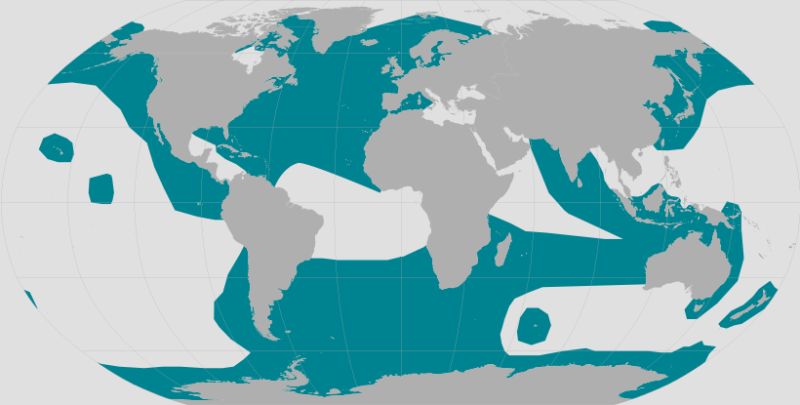

Found in every ocean in the world, they are the most widely distributed of all cetaceans (whales and dolphins). Scientific studies have revealed many different populations with several distinct ecotypes (or forms) of killer whales worldwide—some of which may be different species or subspecies. They are one of the most recognizable marine mammals, with their distinctive black and white bodies. Globally, killer whales occur in a wide range of habitats, in both open seas and coastal waters. Taken as a whole, the species has the most varied diet of all cetaceans, but different populations are usually specialized in their foraging behavior and diet. They often use a coordinated hunting strategy, working as a team like a pack of wolves.

Hunters and fishermen once targeted killer whales. As a result, historical threats to killer whales included commercial hunting and culling to protect fisheries from killer whales. In addition, although live capture of killer whales for aquarium display and marine parks no longer occurs in the United States, it continues to remain a threat globally. Today, some killer whale populations face many other threats, including food limitations, chemical contaminants, and disturbances from vessel traffic and sound. Efforts to establish critical habitat, set protective regulations, and restore prey stocks are essential to conservation, especially for the endangered Southern Resident killer whale population.

All killer whale populations are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Only two populations receive additional special protections under federal law:

- Southern Resident Distinct Population Segment (DPS) (listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act

- AT1 Transient stock (designated as depleted under the MMPA)

Southern Resident killer whales are the only endangered population of killer whales in the United States, ranging from central California to southeast Alaska. Long-term commitments across state and international borders are needed to stabilize the Southern Resident population and prevent their extinction. The Southern Resident killer whale is one of NOAA Fisheries' Species in the Spotlight. This initiative includes animals considered most at risk for extinction and prioritizes recovery efforts.

NOAA Fisheries is committed to the conservation of killer whales and the protection and recovery of endangered populations. Our scientists and partners use a variety of innovative techniques to study and protect them. We also work with our partners to develop regulations and management plans that protect killer whales and their food sources, decrease contaminants in oceans, reduce ocean noise, and raise awareness about the whales and the actions people can take to support their recovery.

Population Status

Several different populations and ecotypes of killer whales are found throughout the world. NOAA Fisheries estimates population size in our stock assessment reports. It is estimated that there are around 50,000 killer whales globally. Approximately 2,500 killer whales live in the eastern North Pacific Ocean—home to the most well-studied killer whale populations.

In recent decades, several populations of killer whales have declined and some have become endangered. The population of AT1 Transients, a stock of Transient killer whales in the eastern North Pacific, has been reduced from 22 to 7 whales since the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. In 2004, NOAA Fisheries designated this stock as depleted under the MMPA based on the results of the status review (PDF, 25 pages).

Scientists estimate the minimum historical population size of Southern Residents in the eastern North Pacific was about 140 animals. Following live-capture in the 1960s for use in marine mammal parks, 71 animals remained in 1974. Although there was some growth in the population in the 1970s and 1980s, with a peak of 98 animals in 1995, the population experienced a decline of almost 20 percent in the late 1990s, leaving 80 whales in 2001. The 2020 population census counted only 72 whales, and three new calves have been born following the census bringing the total of this struggling population to 75. In 2003, NOAA Fisheries began a research and conservation program with congressional funding to address the dwindling population. Southern Residents were listed as Endangered in 2005 under the ESA and a recovery plan was completed in 2008.

Learn more about the different populations and social organization of killer whales

Appearance

Killer whales are mostly black on top with white undersides and white patches near the eyes. They also have a gray or white saddle patch behind the dorsal fin. These markings vary widely between individuals and populations. Adult males develop disproportionately larger pectoral flippers, dorsal fins, tail flukes, and girths than females.

Learn more about the physical features of various populations of killer whales (PDF, 1 page)

Behavior and Diet

Killer whales are highly social, and most live in social groups called pods (groups of maternally related individuals seen together more than half the time). Individual whales tend to stay in their natal pods. Pods typically consist of a few to 20 or more animals, and larger groups sometimes form for temporary social interactions, mating, or seasonal concentrations of prey.

Killer whales rely on underwater sound to feed, communicate, and navigate. Pod members communicate with each other through clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls. Each pod in the eastern North Pacific possesses a unique set of calls that are learned and culturally transmitted among individuals. These calls maintain group cohesion and serve as family badges.

Although the diet of killer whales depends to some extent on what is available where they live, it is primarily determined by the culture (i.e., learned hunting tactics) of each ecotype. For example, one ecotype of killer whales in the U.S. Pacific Northwest (called Residents) exclusively eats fish, mainly salmon, and another ecotype in the same area (Transients or Bigg’s killer whales) primarily eats marine mammals and squid.

Killer whales often use a coordinated hunting strategy and work as a team to catch prey. They are considered an apex predator, eating at the top of the food web.

Where They Live

Killer whales are found in all oceans. While they are most abundant in colder waters like Antarctica, Norway, and Alaska, they are also found in tropical and subtropical waters. The most well-studied killer whale populations occur in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. Resident killer whales have been seen from California to Russia. Offshore killer whales have the largest range of any community, and often occur more than 9 miles offshore. They are not, however, exclusively “offshore”, as they are sometimes seen in coastal nearshore waters. Transient killer whales also occur throughout the eastern North Pacific, and are often seen in coastal waters. Their habitat sometimes overlaps with Resident and Offshore killer whales.

World map providing approximate representation of the killer whale's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the killer whale's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

The average lifespan for male killer whales is about 30 years, but they can live up to at least 60 years. Females typically live about 50 years, but can live up to at least 90 years in the wild.

Females reach sexual maturity when they are between 10 and 13 years old. They are typically pregnant for 15 to 18 months and give birth to a single calf. Calves nurse exclusively for at least a year, but remain in close association with their mother for the first two years. There is no distinct calving season, so birth can take place in any month. The birth rate for killer whales is not well understood. In some populations, birth rate is estimated at every 5 years for an average period of 25 years. Killer whales, beluga whales, narwhals, short-finned pilot whales, and humans are the only known species that go through menopause.

Threats

Entanglement

Killer whales are at high risk of becoming entangled in fishing gear. Once entangled, whales may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances or be anchored in place and unable to swim. Events such as these result in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury, which may ultimately lead to death.

Lack of Food

Overfishing and habitat loss have decreased the amount of prey available to some killer whales. Without enough prey, killer whales might experience decreased reproductive rates and increased mortality rates. This threat is especially important for Southern Resident killer whales because some populations of their preferred prey, Chinook salmon, are also threatened or endangered.

Contaminants

Contaminants enter ocean waters and sediments from many sources, such as wastewater treatment plants, sewer outfalls, and pesticide application. Once in the environment, these substances move up the food web and accumulate in top predators, such as killer whales because of their long lifespan, position at the top of the food chain, and blubber stores. These contaminants can harm killer whales’ immune and reproductive systems.

Despite modern pollution controls, chemical contamination through the food web continues to threaten killer whales. These controls have reduced, but not eliminated, many contaminants in the environment. Additionally, some of these contaminants persist in the marine environment for decades and continue to threaten marine life.

Oil Spills

The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska, was strongly correlated with the direct loss of individual killer whales. However, oil spills can also have an indirect impact on killer whales by affecting the abundance of prey species. In addition, the bioaccumulation of certain contaminants, like those found in oil, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the food web can be seen in apex predators like killer whales—and particularly among the transient population.

Disturbance from Vessels and Sound

When vessels are present, killer whales hunt less and travel more. Noise interference from vessels, as well as from industrial and military activities, interrupts killer whales’ ability to use sound, which in turn disturbs their feeding, communication, and orientation. Increased vessel noise causes Southern Resident killer whales to call louder, expending more energy in the process.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Delphinidae | Genus | Orcinus | Species | orca |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/17/2024

What We Do

Conservation & Management

All killer whales are protected under the MMPA and the Southern Resident population is listed as an endangered species under the ESA. We have focused our conservation efforts to help rebuild endangered and depleted populations on the West Coast and Alaska. Targeted management actions taken to secure protections for these whales and their habitat include:

- Protecting killer whale habitat

- Implementing coast-wide salmon recovery actions

- Collaborating with partners on mitigating contaminants

- Preventing oil spills and improving response preparation

- Minimizing whale watching harassment and reducing vessel impacts

Science

Our research projects have discovered new aspects of killer whale biology, behavior, and ecology and helped us better understand the threats killer whales’ face. This research is especially important in rebuilding endangered and depleted populations and informing management decisions. Our work includes:

- Collecting prey and fecal samples to learn about diet and health

- Aerial photogrammetry to assess body condition and reproduction

- Measuring the response of animals to sound using digital acoustic recording tags

- Measuring pollutant transfer from mothers to offspring

- Measuring energy costs to generate sounds

How You Can Help

Choose Land-Based Whale Watching

Viewing whales from shore decreases the number of boats on the water, which reduces underwater noise that can disturb killer whales.

The Whale Trail includes many land-based observation sites where you can view and learn about killer whales and other marine mammals. Sites are available in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California.

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all small whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards by sea or land.

In Washington State inland waters, it is illegal to approach a killer whale within 200 yards. Please visit Be Whale Wise for more specific instructions.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

Aerial images comparing the sizes of adult male Bigg’s and Resident killer whales, both taken in the Salish Sea off southern Vancouver Island. Images are scaled to lengths calculated during health research by SR3 SeaLife Response, Rehabilitation and Research. Images were collected by John Durban and Holly Fearnbach using a non-invasive drone authorized by research permit 19091 issued by the US National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).

Aerial images comparing the sizes of adult male Bigg’s and Resident killer whales, both taken in the Salish Sea off southern Vancouver Island. Images are scaled to lengths calculated during health research by SR3 SeaLife Response, Rehabilitation and Research. Images were collected by John Durban and Holly Fearnbach using a non-invasive drone authorized by research permit 19091 issued by the US National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).

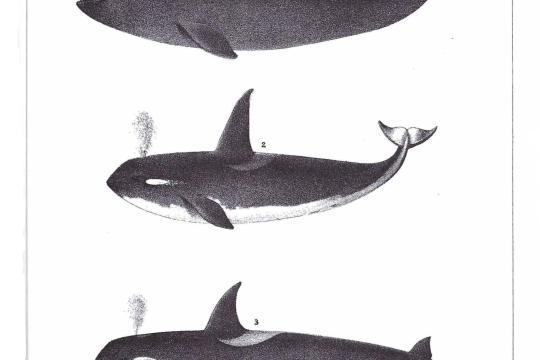

California whaler Charles Melville Scammon first described the killer whales of the West Coast, and documented his observations and findings in a manuscript he sent to the Smithsonian Institution.

California whaler Charles Melville Scammon first described the killer whales of the West Coast, and documented his observations and findings in a manuscript he sent to the Smithsonian Institution.

Credit: Shutterstock

Credit: Shutterstock

Related Species

Populations

Killer whales were once considered monotypic (belonging to one species), but many lines of evidence show that several distinct lineages, or even subspecies, of killer whales exist.

There are three main types of killer whales in the North Pacific: Resident, Transient, and Offshore. Each ecotype differs in appearance, diet, habitat, genetics, and behavior. While all three types share at least part of their habitats, they are not known to interbreed with each other.

Resident Killer Whales

Resident killer whales have rounded dorsal fins and a wide variety of saddle patch markings (the white patch behind their dorsal fins). They range from California to Russia and live in large groups. Four populations of Resident killer whales occur in the Pacific Northwest:

- Southern Residents

- Northern Residents

- Southern Alaska Residents

- Western Alaska North Pacific Residents

Resident killer whales usually eat different varieties of fish, primarily salmon. Southern Resident killer whales prefer Chinook salmon, some of which are endangered.

Transient Killer Whales

Transient killer whales have straighter dorsal fins and have primarily solid white saddle patches. They live throughout the coastal waters of the Pacific Northwest in small groups. Transient killer whales’ diets are more varied and can include squid and other marine mammals such as seals, sea lions, porpoises, dolphins, and other whale species.

Offshore Killer Whales

Offshore killer whales have rounded dorsal fins, a variety of saddle patch patterns, and are generally smaller than the other types of killer whales. They are seen in large groups and have the largest range that can occur up to 9 miles offshore. Offshore killer whales eat fish, including sharks.

Other Populations

In addition to the three ecotypes, distinct populations of killer whales exist throughout the world. Populations are smaller groups within each type of killer whale. For example, there are four different populations of Resident killer whales. Each population has its own unique diet, behaviors, social structure, and habitat.

Killer Whale Social Structure and Behavior

Outside of the North Pacific, other populations of killer whales also have specialized diets. Off the coast of Norway, killer whales feed mainly on herring and other schooling fish. In waters off New Zealand, some killer whales eat stingrays and sharks. In Antarctic waters, killer whales eat minke whales, seals, or Antarctic toothfish. In contrast to killer whales in the North Pacific where specialized diets are characteristic of different ecotypes, killer whales in the Northeast Atlantic are believed to eat both herring and seals.

Killer whales are highly social and individual whales tend to stay in their original pods. Pods typically consist of two to 15 animals, but larger groups sometimes form for temporary social interaction, mating, or seasonal availability of food. Pods differ in size due to behavioral differences, the availability of food, and the number of whales living in a given area.

Pod members communicate with each other through underwater sounds such as clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls. Each pod in the Pacific Northwest possesses a unique set of sounds that are learned and culturally transmitted among individuals. These sounds help keep groups together and serve as family badges.

Pods also work together to hunt. They use a coordinated hunting strategy and work as a team to catch prey.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/17/2024

In the Spotlight

Southern Resident Killer Whale

The Southern Resident killer whales are one of NOAA Fisheries' Species in the Spotlight. This initiative is a concerted agency-wide effort launched in 2015 to spotlight and save the most highly at-risk marine species.

The endangered Southern Residents are an icon of the Pacific Northwest and inspire widespread public interest, curiosity, and awe around the globe. Southern Residents face depleted prey, disturbance from vessels and sound, and show high levels of contaminants from pollutants.

In 2003, NOAA Fisheries began a research and conservation program with congressional funding. This research program is ongoing and has contributed to knowledge of factors affecting the health and recovery of the Southern Resident killer whales. In 2005, the Southern Residents were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and a recovery plan was completed in 2008.

The population continues to struggle and has declined over 10 percent since 2005. The summer population census for 2020 counted only 72 Southern Resident killer whales with several new calves born since the census. We have come a long way in our understanding and ability to protect this unique population, and in 2014 we summarized a decade of research and conservation activities in a special report.

Where Southern Resident Killer Whales Live

During the spring, summer, and fall, the range of Southern Resident killer whales includes the coastal and inland waterways of Washington State and the transboundary waters between the United States and Canada. We have been learning more about their winter movements and range through dedicated and collaborative research efforts. They have been spotted as far south as central California during the winter months and as far north as Southeast Alaska. In recent years, we have increased our knowledge about their coastal habitat use through passive acoustic monitoring and the collection of new sightings.

Population Status

Scientists estimate the minimum historical population of Southern Residents numbered about 140 animals. Following a live-capture fishery in the 1960s, 71 animals remained in 1974. Although there was some growth in the population in the 1970s and 1980s, with a peak of 98 animals in 1995, the population experienced a decline of almost 20 percent in the late 1990s, leaving 80 whales in 2001. The most recent population in 2020 counted only 72 Southern Resident killer whales.

Threats

Noise and overcrowding from boat traffic, high contaminant levels, as well as a scarce supply of their preferred prey—salmon—pose serious threats to this endangered population.

It is hoped that focused efforts and critical investments within NOAA Fisheries, and continued engagement with our vital partners, will stabilize and prevent the Southern Resident killer whale’s extinction. Past research has shown that some of the most important threats facing the whales, such as prey limitation and high contaminant levels, cannot be addressed without a long-term commitment. Recovery of threatened and endangered salmon, for example, is a monumental task in itself and is expected to take many years.

The threat of contaminants is also challenging, particularly because the whales remain contaminated by chemicals that were banned decades ago. NOAA Fisheries implemented vessel regulations in 2011 and coordinates with Washington State and Canada on vessel guidelines and regulations. Some mysteries also persist. For example, are there health issues, like disease, that we have not yet uncovered? Will increases in salmon abundance benefit the Southern Resident whales, or will any increases be consumed by other salmon predators? We also must consider new threats and actions as we look to a future with climate change, new alternative ocean energy projects, and continuing development along our coasts and in our ports. In the next 5 to 10 years, several high-priority projects are planned to help answer these remaining questions and inform management actions to advance recovery.

Research Activities

New information on coastal distribution and habitat use, gathered from both acoustic monitoring and satellite tagging, have informed a proposal for additional critical habitat for the whales. Digital acoustic suction cup tags are shedding light on foraging behavior for the whales and how finding and catching salmon may be affected by vessels and sound. Seasonal health assessments, habitat use, and understanding body condition changes and times and places with prey limitations will all be taken into consideration when determining the need for additional conservation actions.

Species Recovery

With more than 10 years of funding, collaboration, and ingenuity, we have taken substantial and important steps to aid Southern Resident killer whale recovery. Research projects have illuminated new aspects of killer whale biology, behavior, and ecology and helped us better understand the challenges this population faces. Targeted management actions, informed by research, have been taken to secure protections for the whales and their habitat, including:

- Designation of more than 2,500 square miles of critical habitat in inland waters of Washington and a proposal for more than 15,600 square miles of critical habitat along the Washington, Oregon and California coasts

- Regulations to protect the whales from vessel effects

- Coordination with coastwide efforts to implement salmon recovery actions

- Collaboration with partners on monitoring and minimization of harmful contaminants and learning more about other threats to whale health

- Oil spill response plans to ensure we are prepared in the event of a spill

Understanding the factors that affect the whales' health will help us identify the most important threats, how they interact, and what we can do to reduce their effects. New technologies are being developed to better understand risks of disease, assess individual body condition, and gain a better understanding of the health effects of carrying large contaminant burdens. We also plan to explore additional management actions outlined in the recovery plan to stabilize the population.

Recovery of the Southern Residents and their preferred salmon prey, as well as protection of their broad and diverse habitat, is a long-term process that requires support over a large geographic area, from California to southeast Alaska. The continued success of research and conservation programs relies on leveraging resources and maximizing effects through partnerships. For example, the whales spend significant time in Canadian waters and are listed as endangered under the Canadian Species at Risk Act so transboundary coordination has been, and will continue to be, important to recovery.

Our recovery criteria are built around a timeframe of 14 to 28 years based on the biology of these long-lived animals. It will take at least that long for us to evaluate the effectiveness of the protective measures put in place in the past several years. The past federal funding and effort have secured a strong foundation of research and conservation, which we can build on to secure recovery of this iconic species for future generations.

Species in the Spotlight Priority Actions

We developed a Species in the Spotlight 2021–2025 Priority Action Plan that builds on the recovery plan and the 2016–2020 Priority Action Plan and details the focused efforts that are needed over the next five years. The plan lists key actions NOAA Fisheries and its partners can take from 2021 to 2025 to help recover the species. These actions include:

- Protect killer whales from harmful vessel effects.

- Target conservation of critical prey.

- Improve knowledge of killer whale health.

- Raise awareness and inspire stewardship for killer whales.

In our first five years of the Species in the Spotlight initiative, we have:

- Identified and prioritized essential Chinook salmon stocks to increase critical prey through coordinated salmon management and recovery

- Reduced impacts of vessels through expanded enforcement and outreach to improve compliance with rules and guidelines

- Developed new partnerships through Washington Governor's Orca Task Force

- Used whale distribution and prey data to propose and expand designated critical habitat in coastal waters

- Collected health samples using new technologies

- Expanded outreach and education programs

2017 Species in the Spotlight Hero Award

Jeff Hogan has partnered with NOAA for more than a decade and has helped implement many important recovery actions for endangered Southern Resident killer whales. Jeff is the Executive Director of Killer Whale Tales, an environmental education program. It uses storytelling and field-based science to inspire students to take an active role in the conservation of Pacific Northwest killer whales.

Learn more about Jeff Hogan's work

2019 Partner in the Spotlight Award

In 2018, the Southern Resident Killer Whale Task Force was established by Governor Jay Inslee. Governor Inslee brought state authorities, significant investments, and new members of the community to the ongoing fight to recover the iconic Southern Resident killer whales. The Task Force developed recommendations for short- and long-term actions needed to protect and recover Southern resident killer whales.

Read more about the Southern Resident Killer Whale Task Force's work

2021 Partner in the Spotlight Award

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) Killer Whale Research and Conservation Grant Program was established in 2015 through a contribution pledge from SeaWorld Entertainment Inc. The program has awarded 38 grants totaling more than $12.8 million, supporting projects to increase prey availability, improve habitat quality, and strengthen management through research. NFWF has also taken on special projects such as coordinating a workshop in 2018 to contribute to the Priority Prey Report and increasing education and awareness of the Be Whale Wise program.

Learn more about the NFWF Killer Whale Research and Conservation Grant Program’s work

2023 Partner in the Spotlight Award

Quiet Sound, a program of Washington Maritime Blue, officially launched in December 2021 after several years of development to help fulfill recommendations of the Southern Resident Orca Task Force assembled by Washington Governor Jay Inslee to support implementation of shipping noise reduction initiatives. Once launched, Quiet Sound moved quickly to take action to reduce effects of noise on whales, launching five projects in their first year, and culminating in a successful voluntary slowdown for commercial vessels in October 2022-January 2023.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/17/2024

Management Overview

Killer whales are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The AT1 Transient population is also considered depleted under the MMPA. Only one population of killer whales is listed under the Endangered Species Act. The Southern Resident Distinct Population Segment (DPS) of killer whales has been listed as endangered under the ESA since 2005. This means that the population of Southern Residents is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

We work to protect all populations of killer whales. However, our management work primarily focuses on recovery of the endangered Southern Resident population.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Action

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries develops and implements recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. The ultimate goal of the Southern Resident killer whale recovery plan is to recover the species, with an interim goal of down-listing its status from endangered to threatened. The major actions recommended in the plan are:

- Support salmon restoration efforts in the region to ensure an adequate prey base

- Reduce existing and monitor emerging contaminants

- Reduce vessel effects by improving whale watching guidelines and establishing regulations or protected areas as needed

- Prevent oil spills and improve response preparation

- Use available protections to minimize effects from human-caused sound

- Enhance public awareness and education

- Improve responses to live and dead killer whales

- Coordinate efforts with Canadian agencies, and with U.S. federal and state partners

- Conduct research to facilitate conservation efforts

Species Recovery Contact

Southern Resident DPS

Lynne Barre, Recovery Coordinator

Read the recovery plan for Southern Resident killer whales

Two Southern Resident killer whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Implementation

The ESA authorizes NOAA Fisheries to appoint recovery teams to help develop and implement recovery plans. Rather than convening a recovery team for Southern Resident killer whales, we used an open public process to engage as many interested stakeholder groups and individuals as possible and work with a variety of partners to implement the actions in the plan.

Critical Habitat

Once a species is listed under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries evaluates and identifies whether any areas meet the definition of critical habitat. Those areas may be designated as critical habitat through a rulemaking process. The designation of an area as critical habitat does not create a closed area, marine protected area, refuge, wilderness reserve, preservation, or other conservation area; nor does the designation affect land ownership. Federal agencies that undertake, fund, or permit activities that may affect these designated critical habitat areas are required to consult with NOAA Fisheries to ensure that their actions do not adversely modify or destroy designated critical habitat.

In 2006, NOAA Fisheries designated inland waters of Washington State as critical habitat for the Southern Resident killer whale. We designated this habitat because it contains three features essential to the conservation of Southern Residents:

- Water quality to support growth and development

- Enough prey to support individual growth, reproduction, and development, as well as overall population growth

- Passage conditions to allow for migration, resting, and foraging

In 2014, NOAA Fisheries started a process to revise the critical habitat of Southern Residents in response to a petition (PDF, 35 pages). In 2021, NOAA Fisheries published a final rule to modify critical habitat to include coastal waters off of Washington, Oregon, and California.

Learn more about the revised critical habitat designation for Southern Resident killer whales

Learn more about critical habitat for Southern Resident killer whales

Conservation Efforts

Supporting Salmon Restoration Efforts

Chinook salmon stocks are currently lower than historic levels, putting Southern Resident killer whales at risk for decreased reproductive rates and increased mortality rates. Some species of West Coast salmon are currently protected under the ESA and Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. NOAA Fisheries coordinates habitat restoration efforts in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California to help restore salmon runs. Our scientists have also organized workshops and panels to better understand the effects of salmon fisheries on Southern Resident killer whales.

Learn more about salmon restoration

Reducing Contaminants

Killer whales are especially vulnerable to chemical contaminants because they are at the top of the food web. To address this, NOAA joined the Puget Sound Partnership, a program that helps prevent contamination in Southern Resident habitat and collaborated with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Washington State agencies to develop a plan to fill gaps in research and monitoring. NOAA's Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program, which cleans up existing contamination, also has several active projects in the Pacific Northwest and California.

Learn more about environmental contaminants

Preventing Oil Spills and Improving Response Preparation

Southern Resident killer whales are at risk of harm in the event of an oil spill. To reduce the risk of a spill, Washington’s Department of Ecology created the Spill Prevention, Preparedness, and Response Program. To minimize the effect of a potential spill on Southern Residents, NOAA developed the Marine Mammal Oil Spill Response Guidelines. Additionally, the Northwest Area Contingency Plan (PDF, 51 pages) includes methods to discourage killer whales from swimming into spilled oil.

Learn more about preventing oil spills

Learn more about minimizing disturbance of Southern Resident killer whales from vessels

Coordinating with Canadian Agencies, and U.S. Federal and State Partners

Because Southern Residents range from California to Alaska, recovery of their population requires cooperation across state and national borders. NOAA is coordinating with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Center for Whale Research, and other partners to conduct research and implement recovery actions.

Learn more about interagency coordination and cooperation

Developing Vessel Regulations and Minimizing Whale Watching Harassment

NOAA Fisheries supports responsible viewing of marine mammals in the wild and has adopted a guideline to observe all marine mammals from a safe distance of at least 100 yards by sea or land.

NOAA Fisheries and Washington State have also taken steps to reduce threats to killer whales by regulating how close a vessel may get to the species in Washington State waters. This reduces disturbance to the animals and the potential for negative interactions. The federal regulations make it illegal to:

- Approach within 200 yards of a Southern Resident killer whale

- Position a vessel to be in the path of a Southern Resident whale at any point located within 400 yards of the whale

- Feed a Southern Resident killer whale

Learn more about vessel regulation and viewing distances for Southern Residents in Washington State

We work with many partners to promote the Be Whale Wise campaign to educate boaters on the regulations and viewing guidelines in place to protect killer whales and all marine mammals. We also encourage land-based whale watching, as part of the Whale Trail, as a way to enjoy viewing without any effects to the whales.

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Killer whales have never been part of a declared unusual mortality event. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Regulatory History

All marine mammals, including killer whales, are protected in the United States under the MMPA. Southern Residents are listed as endangered under the ESA.

AT1 Transient Population

In 2002, the National Wildlife Federation petitioned (PDF, 10 pages) NOAA Fisheries to designate the AT1 Transient pod as depleted after its drastic decline following the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. The spill was strongly correlated with the deaths of most of the AT1 Transient pod. There have been no observed births to the AT1 stock of the North Pacific transient killer whale population since 1984, and the population has steadily declined to 7 individuals.

In 2003, NOAA Fisheries reviewed a petition concerning the possibility that the AT1 killer whale group of Prince William Sound may be genetically distinct from other killer whales in Alaska, and may be depleted.

In 2004, NOAA Fisheries designated the AT1 stock as depleted under the MMPA.

Southern Resident Population

In 2005, the Southern Resident population was listed as endangered under the ESA. We designated critical habitat for Southern Residents in 2006 and a recovery plan was completed in 2008.

In 2015, we issued a 12-month finding on a petition to revise critical habitat for Southern Residents.

In December 2016, we completed a 5-year status review of Southern Resident killer whales.

In 2019, NOAA Fisheries published a proposed rule to modify critical habitat.

Key Actions and Documents

More Information

- Report a Stranded or Injured Marine Animal

- Southern Resident Killer Whales on the West Coast

- Petition to Include Lolita in ESA Listing of Southern Resident Killer Whales

- Marine Mammal Permits and Authorizations

- Endangered Species Conservation

- Marine Life Viewing Guidelines

- Whale Alert Smartphone App

- Killer Whale Contacts

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/17/2024

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries scientists are leading the effort to answer key questions about the risk factors potentially affecting killer whales, with a special focus on the Southern Resident population. Current research focuses on killer whales’ behavior, ecology, health, and human-caused effects.

Shipboard Studies

Our scientists and collaborators collected length and width data for killer whales using both vessel-based laser photogrammetry and aerial photography from unmanned aerial systems (hexacopters). These metrics will be used to infer growth trends and current body condition, respectively, which will be related to trends in returning Chinook salmon—the whales’ primary prey. This research aims to provide a comparative assessment of nutritional status to guide management of these two protected populations.

Learn more about our photogrammetry research (PDF, 2 pages)

A Southern Resident killer whale "spy hopping" off San Juan Island, Washington. Credit: NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center

Acoustic Science

NOAA Fisheries' researchers and collaborators use digital acoustic recording tags, recording the sounds they receive and the sounds they produce, to examine sound exposure, sound use, and behavior of Southern Residents in their summer habitat. This research helps address threats like vessel disturbance, noise exposure, and effects on feeding.

Learn more about digital acoustic recording tags

Measuring Contaminant Transfer From Mothers to Offspring

Scientists study the transfer of contaminants from mother to offspring through blood during gestation and through milk during lactation. This research helps us understand whether young whales are at greater risk than adults for negative health effects from contaminants.

Learn more about pollutant transfer

Measuring Energy Costs to Produce Sounds

Our scientists measure the metabolic cost (how much energy the whales used) of specific behavioral and acoustic responses to vessel disturbance. We use the results to assess the cumulative energetic costs of Southern Residents to vessel disturbance.

Learn more about the energetic costs of vessel disturbance

Stock Assessments

Determining the size of killer whale populations helps resource managers determine the success of conservation measures and regulations. Our scientists collect population information on killer whales from various sources and present the data in annual stock assessment reports.

Southern Resident Killer Whale Monitoring and Research

Check out what our scientists from the West Coast Region are working on

Check out Southern Resident Killer Whale Research in the Pacific Northwest

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/17/2024

Documents

Recovering Threatened and Endangered Species Report to Congress (FY 2021-2022)

This Report to Congress summarizes efforts to recover all transnational and domestic species under…

Killer Whale Entanglements in Alaska

Summary Report: 1991-2022 NMFS has documented killer whale entanglements through a variety of…

2021 Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation

The Southern Resident killer whale Distinct Population Segment was first listed as Endangered in…

Species in the Spotlight: Priority Actions 2021-2025, Southern Resident Killer Whale

The Species in the Spotlight initiative is a concerted agency-wide effort to spotlight and save…

Data & Maps

Recovery Action Database

Tracks the implementation of recovery actions from Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans.

Outreach & Education

Actividad de asociación de aleta de orca (en español)

En esta actividad, los participantes identificarán a orcas individuales en la manada L asociando…

Actuar en favor de las orcas residentes del sur (en español)

Las orcas residentes del sur son iconos del noroeste del Pacífico.

Salvar a las orcas residentes del sur (en español)

Una unidad de aprendizaje basada en proyectos para la escuela secundaria

Project-Based Learning: Saving the Southern Resident Killer Whales

By employing the principles of project based learning, this unit empowers students to steer their…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/17/2024