Ah, oysters. Some folks like to eat 'em, whether raw or in tasty recipes. Others like to go fishing near the reefs they form, knowing that fish and crabs like to use the hiding spots as habitat. Still others appreciate the benefits oysters bring to the ecosystem by removing nitrogen and trapping sediment—helping support healthier water quality.

But in the Chesapeake Bay, in recent decades the oyster population plummeted, due to disease, poor water quality, and overharvesting. Realizing the many benefits oysters bring, NOAA and other agencies are partnering to restore oyster reefs in selected tributaries of the Chesapeake.

These benefits are so important that the Chesapeake Bay Program—a partnership of federal, state, and local governments, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations—included a goal to restore oysters to 10 tributaries by 2025 in their 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement. In Maryland, restoration is under way in Harris Creek and the Little Choptank and Tred Avon rivers, while surveys are being conducted in the St. Mary's River to inform restoration plans; selection of a fifth tributary is in progress. In Virginia, the Great Wicomico, Lafayette, Lynnhaven, Piankatank, and lower York rivers are restoration sites.

NOAA funds large-scale in-water restoration work in Maryland and Virginia, and provides overall project advice through its role leading the Bay Program's Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team, under which the oyster restoration efforts are nested. Critically, the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office also provides a significant amount of science to make the restoration projects as effective and efficient as possible.

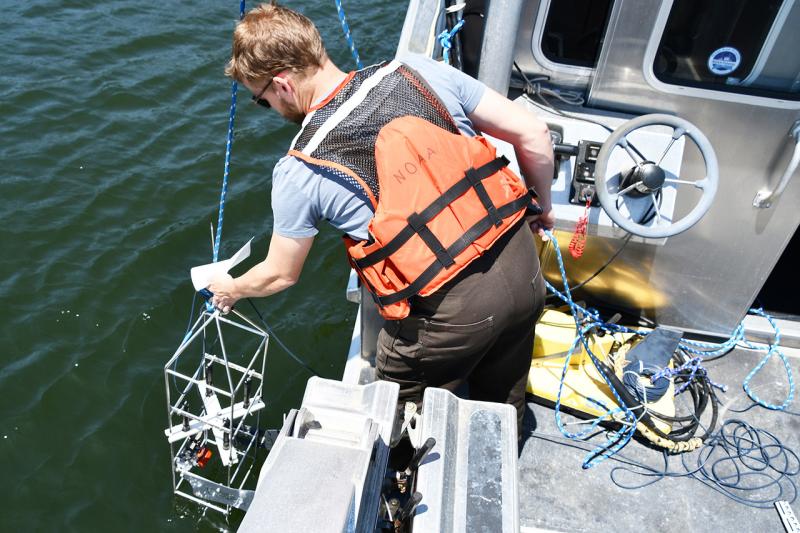

For each tributary selected for this large-scale restoration, first, the areas within that river that could be restored must be identified. The NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office maps areas using sonar technology from on board the Research Vessel Potawaugh, a 32-foot aluminum catamaran that can operate in shallow water, necessary to research areas for potential oyster restoration. The team also uses groundtruthing and visual inspection techniques.

Different kinds of sonar can be used to map different aspects of river bottoms, providing data that indicates areas that have hard bottom or that may have historically been home to oyster reefs. The data acquired in these surveys is then analyzed and documented to show areas that are restorable. This information is used by the restoration partners as they develop a blueprint for how the restoration will proceed.

NOAA science doesn't stop once the areas where reefs will be built and baby oysters will be planted are determined. To ensure project success—and to help restoration partners learn from their efforts—NOAA does additional survey work on restored reef areas once they have been constructed to establish a baseline, and then again three and six years after those reefs are restored, to track things like reef size and height. NOAA works with other partners, including the Oyster Restoration Partnership and the University of Maryland, that monitor biological elements to track reef health as well. All this information is compiled into a report released each year by NOAA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

So far, reports from reefs restored in the NOAA Choptank Habitat Area show great success—for example, 97% of reefs constructed in 2013 in Harris Creek, Maryland, met the requirements for oyster density and biomass in the fall of 2016. NOAA scientists will continue to monitor these and other reefs to track their progress—and to learn more about healthy habitat.