The Pacific sleeper shark is the largest shark in Alaska, and possibly the largest predatory fish in the ocean. It is also one of the most vulnerable of all managed fish stocks in Alaska waters.

“Yet we still know little about even its most basic biology,” said Beth Matta, research fisheries biologist at the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

A new collaborative NOAA Fisheries study takes an important step toward better understanding and managing the Pacific sleeper shark. Researchers compiled knowledge from a wide variety of sources to provide important new insights into its biology and ecology. They identified and prioritized research needs to better assess and manage this species.

“We can’t manage what we don’t understand,” said Matta, who led the study. “We wanted to create a one-stop shop for information on Pacific sleeper sharks—a resource that others can use.”

Slow Growth and Low Production Lead to Vulnerability

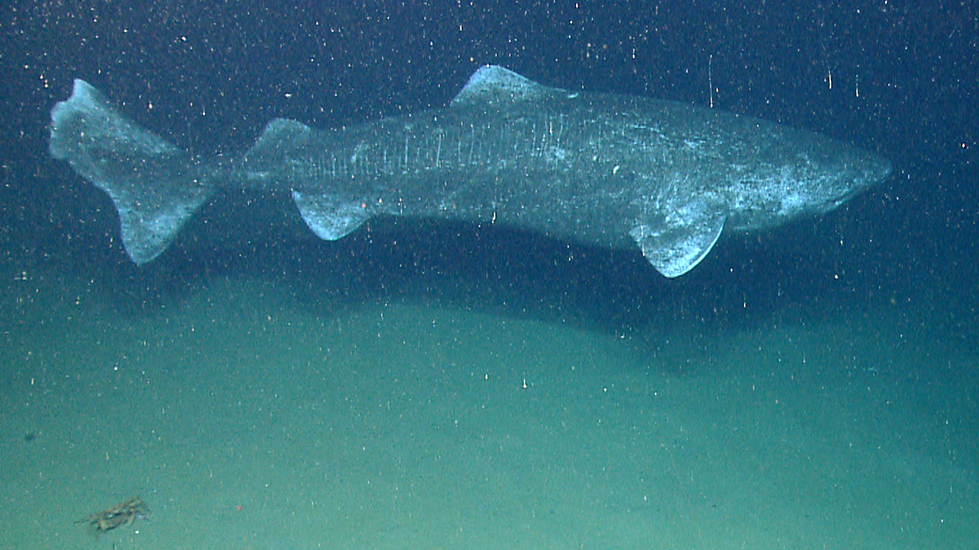

The Pacific sleeper shark, named for its sluggish nature, lives throughout the Pacific Ocean. It has been found in shallow intertidal zones, and sighted by submersibles at depths beyond a mile underwater. It is encountered by humans most often as unwanted bycatch on commercial fishing vessels.

Like many other sharks, the Pacific sleeper shark likely grows slowly, matures late, and has a long lifespan and low productivity. These qualities make it highly susceptible to overfishing.

“Sustainable fishing rates for long-lived sharks are very low. For example, the spiny dogfish, a Pacific sleeper shark relative with a lifespan of 100 years, can tolerate harvest rates of only about 3 percent,” said study coauthor Cindy Tribuzio, NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “Pacific sleeper sharks potentially take that to extremes.”

In Alaska waters, the majority of Pacific sleeper shark mortality is due to fisheries bycatch. Observed declines in certain parts of its range, coupled with its low productivity, have led to conservation concerns. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council highlighted conservation concerns in its most recent stock assessment review.

Challenges to Assessment and Management

Despite its great size, wide range, interactions with humans, and high vulnerability, the Pacific sleeper shark has been little studied until recently. This is due to its lack of commercial value, inaccessible habitats, and the difficulty involved in safely landing and handling such large animals aboard ships.

Large as they are, the Pacific sleeper sharks encountered by ships have nearly all been juveniles. Adult Pacific sleeper sharks are rarely encountered. No pregnant female has ever been retained.

This has led scientists to believe that mature sharks may live in abyssal habitats, 3000-6000 meters deep. Very large sharks—up to an estimated 23 feet—have been caught on submersible cameras at great depths. None larger than 14 feet has ever been measured from fishing or survey vessels.

“A large portion of the population remains unseen and unsampled,” Tribuzio said.

The lack of data on the Pacific sleeper shark’s movements, reproduction, and population size makes it challenging to develop effective conservation and management strategies.

“We don’t have a lot to go on for managing this species. Right now they are managed based on historical catch. That’s not ideal, especially for a highly vulnerable species,” Tribuzio said. “The more information we can gather, the better we can develop and apply alternative methods that will do a better job of assessing this and other data-limited species.”

Gathering Knowledge

Matta’s first step was to scour the existing literature to find all that is known—and not—about Pacific sleeper sharks. The search uncovered many obscure resources. “Some of them were more than 100 years old,” Matta said.

The study borrowed some information from Greenland sharks. The two species are so closely related that they can interbreed and are difficult to distinguish. However, the Greenland shark is much better studied because it has a long history of being fished for its liver oil and meat.

Much of the recent data came from Alaska Fisheries Science Center research. “It was largely amassed through Cindy [Tribuzio]’s efforts and projects over the years,” Matta said.

The researchers also partnered with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, who provided additional data and a Canadian perspective.

“Almost all the research we have done and are doing is highly collaborative. We especially work with fishing industry partners a lot,” Tribuzio said. “A lot of our research could not have been accomplished without their support and the measurements and samples they collect.”

Advancing Our Understanding of Pacific Sleeper Sharks

The study highlights a number of trends and new findings that provide valuable information for Pacific sleeper shark management and conservation.

For example, fewer Pacific sleeper sharks have been observed in recent decades off Alaska and Taiwan, while more have been seen in Russian waters.

New genetic evidence suggests that the Pacific sleeper shark is one big stock in the whole Pacific Ocean, from Alaska all the way to the south end of the southern hemisphere. “We used to think there were three large species in the genus: Pacific sleeper shark, southern sleeper shark, and Greenland shark,” Matta said. “Now we know the southern sleeper shark is not genetically distinct.”

Evidence also points to potential critical nursery habitat for Pacific sleeper sharks in the Bering Sea. Surveys have encountered aggregations of young sharks, and recent genetic evidence linked siblings in the area.

Radiocarbon aging of the eye lenses of a 10-foot Pacific sleeper shark indicated that the growth rate was very slow. However, it was still twice as fast as that of Greenland sharks—which can famously live up to 400 years.

A 14-foot deceased female caught “by sheer awesome luck” in the Aleutians last summer provided a rare opportunity to study a potentially maturing female Pacific sleeper shark. “We have the eyes—they’re the size of cantaloupes,” Tribuzio said. “We hope to do bomb radiocarbon analysis on the eye lenses to determine the age.”

A clearly immature female was found to be at least 35 years old. “That indicates not only extreme longevity, but also delayed maturity,” Tribuzio said. “All those pieces together suggest a high susceptibility to becoming overfished.”

Future Steps Toward Better Assessment and Management

“With the information we compiled in this study, we were able to demonstrate the need to prioritize Pacific sleeper shark assessment efforts,” Tribuzio said. “And that we need to think out of the box on how to manage this species given its vulnerability and challenges to assessing it.”

Ongoing Alaska Fisheries Science Center research will continue to fill knowledge gaps for Pacific sleeper sharks, including longevity estimates, bioenergetics, movements, and reproduction. Catch estimates have improved over the past decade thanks to the teamwork of scientists and fishermen. Machine learning is being used to process electronic monitoring video data. A new project is estimating shark ages from eye lenses. Tribuzio is exploring and pioneering the use of alternative methods for assessing severely data-limited species to better inform decisions about its conservation.

“These animals are truly fascinating biologically—wildly different from everything else we work with. People care—they want to help. Now they are starting to see the results of their efforts,” Tribuzio said. “It’s very exciting to take the efforts of all of the people involved and turn it into actionable information that informs conservation of the species.”

“The more we learn about these sharks, the more we care about keeping them around into the future,” Matta said. “And there is so much more to learn.”

This research was a collaborative effort among the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Alaska Pacific University, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the University of Hawaii.