![ArcticCodOilStudy2.jpg]()

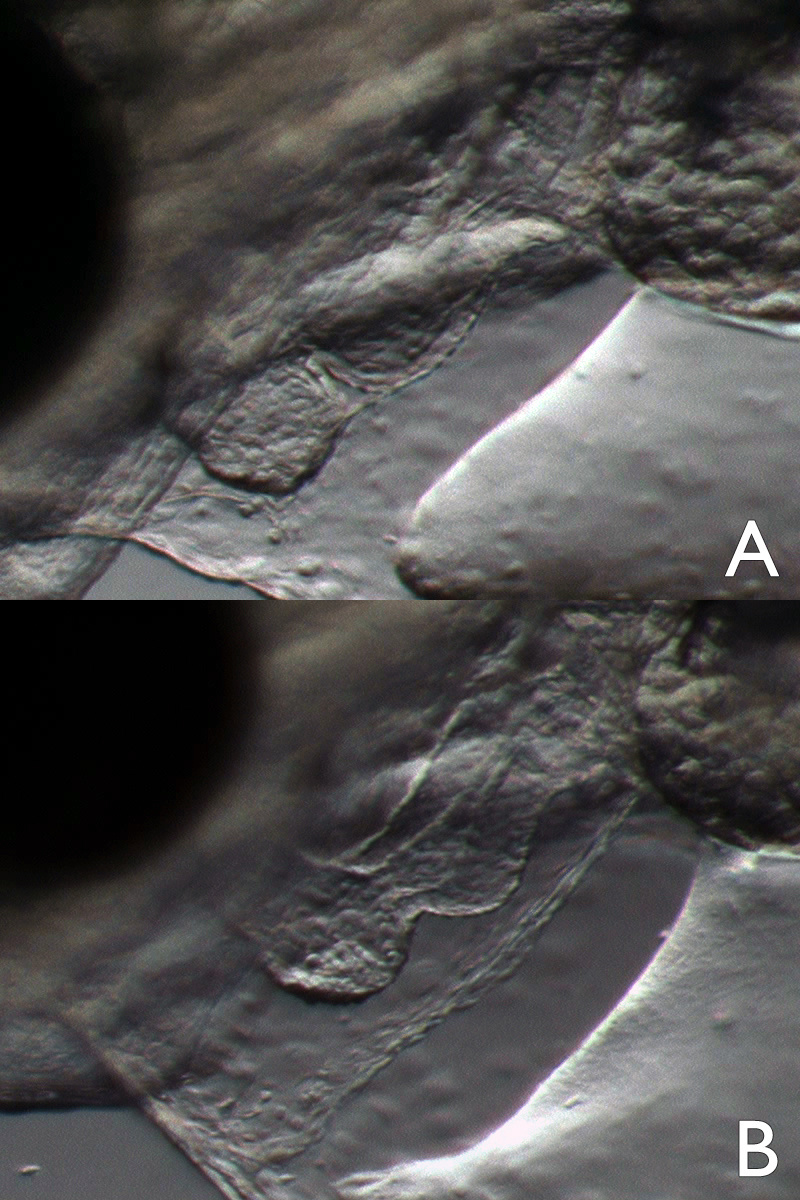

Zoomed to focus on the heart, and the membrane that surrounds it, called the pericardium. The top is the control treatment (A), and the heart is tucked up closely behind the jaw, with the pericardial membrane wrapped closely against it. In the bottom oil-exposed larva (B), the heart is smaller and fully visible as it is pulled away from the jaw. There is edema fluid surrounding it, pushing the pericardial membrane down away from it.

Laurel and fellow scientists at Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s Newport, Oregon facility have had success cultivating and rearing Arctic fish. In fact, the Newport Laboratory is one of the only facilities in the world with this capability.

After adult Arctic cod spawn, their eggs typically float near the surface of the water. Should an oil spill occur, they would be vulnerable to floating and dispersed oil.

With the help of Norwegian technology, the scientific team was able to simulate how an oil spill might affect eggs in the ocean.

Scientists exposed eggs to low concentrations of crude oil for three days during their 40-day embryo developmental phase. This short exposure is similar to what might happen in the environment after a spill. The eggs collected droplets of oil on their egg shells and accumulated toxic chemicals in their bodies.

“Not surprisingly, the crude oil had immediate toxic effects, and some embryos died. We also saw physical deformities as eggs developed. Some had misshapen jaws and malformed hearts with irregular and slow heart rates,” said John Incardona, a research toxicologist at NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center. “We observed similar effects in salmon and herring in Prince William Sound after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska and on Atlantic haddock in studies with our Norwegian partners.”

According to Incardona, more startling were the delayed impacts on later stages of fish development, when eggs became larvae and juveniles.

Scientists found that even when larvae and juveniles looked normal, they weren’t.

In general, test larvae and juveniles were smaller. They were 25-30 percent smaller than larvae and juveniles reared under normal conditions (no oil exposure).

But the most important finding was that exposed eggs, when they reached larval and juvenile stages of development, were not able to effectively process and store fat. Young fish need fat reserves to make it through winter months when prey are less abundant.

Value of This Study for Ecosystem Management

The new findings can help resource managers project how Arctic cod populations will respond to future oil spills. This will improve estimates of environmental risk and guide the development of mitigation measures, the latter to reduce the likelihood of accidents in forage fish spawning habitats.

In the event of a future spill, the data from this study can also be used to assess potential losses (injury) to cod and the food webs they support.

Scientists have been studying oil spill impacts on marine species for decades,” said Nat Scholz, leader of the Ecotoxicology Program at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

![ArcCod_control - Artic Cod.jpg]()

Newly hatched Polar cod larvae, roughly 2 weeks after the oil exposure period. The top image (A) is from a control treatment incubated in clean seawater, the bottom image (B) was exposed to 900 micrograms per liter dispersed oil. The clear globule beneath the organs just behind the head is the yolk sac. In the larva from the oil-exposed treatment, the clear space hollowed out into the yolk represents edema, or fluid accumulating from the heart because it isn’t pumping properly.

“Even so, we’re only just beginning to understand how very subtle forms of toxicity during early development can reduce survival much later in life. Also, how oil impacts one species can influence patterns of energy flow through more complex marine communities, particularly in fragile but still poorly understood ecosystems such as the Arctic.”

Scientists noted that habitat conditions in the Arctic are changing. Other types of environmental stress might compound the effects of oil exposure. Examples include ocean acidification, increasing seawater temperatures, and increasing sunlight (ultraviolet irradiation) in ice-free surface waters. Understanding possible interactions between oil toxicity and thermal stress is a priority because Arctic oceans are warming at a faster rate than temperate zones around the world.

“Continued research on the possible effects of oil exposure on marine species is critical to support responsible development and protect valuable Arctic marine resources and ecosystems,” added Laurel.

Additional Resources