One of the best ways to understand whales is to listen to them. A new artificial intelligence (AI) program named INSTINCT is helping scientists study whales by learning their calls.

The Alaska Fisheries Science Center Marine Mammal Laboratory developed Infrastructure for Noise and Soundscape Tolerant Investigation of Nonspecific Call Types, or INSTINCT. It was developed to detect and identify whale calls from underwater acoustic recordings. Automating this analysis means data critical for whale conservation gets to managers years—sometimes decades—faster. This timely delivery is more important now than ever as climate change is rapidly transforming ecosystems. And although INSTINCT was developed for Alaska, it is adaptable for use across all oceans.

“INSTINCT has allowed us to explore research questions in Alaska that would be impractical to pursue with manual analysis on the timeframes needed for management,” said Dan Woodrich, NOAA Affiliate at the Marine Mammal Laboratory, who developed the INSTINCT program. “We hope to see it become a go-to tool for marine mammal research around the world.”

Listening to Whales: Passive Acoustic Monitoring

Alaska waters are home to a rich diversity of marine mammals, including the world’s most endangered great whales. Collecting the scientific information needed to conserve and protect these species is a colossal challenge. Many migrate long distances across this vast, remote, and harsh marine environment. Monitoring these animals visually from air or sea is difficult and expensive.

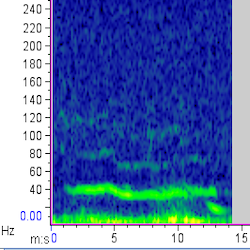

Passive acoustic monitoring—listening underwater—is a cost-effective method to monitor marine mammals over seasons and years. The Marine Mammal Laboratory has maintained an array of moorings in Alaska waters from the southern Bering Sea to the high Arctic since the late 2000s. The moorings are equipped with underwater microphones (hydrophones) to record ocean sounds. These generate huge amounts of data that must be analyzed to detect and identify marine mammal calls. Until recently, these data were only analyzed by humans—time-consuming and technically difficult work. Now scientists are training AI to identify some types of marine mammal signals from the sound recordings.

Training AI to a Human Gold Standard

INSTINCT was developed to provide a fast, accurate, more efficient tool to detect and classify marine mammal calls from acoustic recordings.

Recently, INSTINCT detected and classified 18 million fin whale calls (many individual whales making repeated calls) with less than 2 months of manual verification. They were taken from more than 25 mooring sites over a span of 13 years of Arctic recordings. This saved more than 6 years of equivalent manual review effort. It provided information on the seasonal distribution of fin whales in the Bering and Chukchi Seas.

“INSTINCT was instrumental in revealing long-term changes in the acoustic behavior of fin whales in the Eastern Bering Shelf region, because it can extract information on an individual call basis,” said Jessica Crance, biologist with the Acoustics group at the Marine Mammal Laboratory. “This is a critical component for future work using passive acoustic recordings to obtain estimates of whale density and abundance.”

But decades of manual analysis was what set the stage for INSTINCT’s capabilities.

“Our Alaska dataset is ripe for using AI because we have more than 14 years of data from more than 20 sites already analyzed by people,” Woodrich said. “That’s pretty rare!”

The work of human analysts will continue to be essential in the future.

“When you’re training AI, verification by humans is the gold standard. Humans will still have to validate identifications every year, especially as new species encroach on the Arctic. Humpback songs will change from year to year. Shipping activity will change. Noise profiles will change,” Woodrich explained.

But AI frees humans to concentrate on the complex, skilled aspects of the work.

“A big part of what AI does is streamline efficiency for repetitive work,” Woodrich said. “That gives human analysts time to focus on what humans do best—make the difficult decisions.”

Detecting Whales in a Sea of Noise

Alaska marine ecosystems are full of life—and noise. Creaking sea ice, ship traffic, and a multitude of vocal marine mammals create a complex underwater soundscape.

The challenge is not just identifying whale calls, but distinguishing them from all the other sounds. INSTINCT can do that—to a point.

“The arctic marine soundscape has some incredibly difficult features. Very few species make the same signal year-round. Some will switch from making simple signals to elaborate songs during autumn migrations. Signals produced by different species are often similar. And many species calling at the same time can create an underwater cacophony," Woodrich said. “These sections are too nuanced for where AI is in our field right now to interpret. That’s where human attention is needed."

Learning Marine Mammal Calls

INSTINCT detectors and classifiers have been developed so far for six different calls:

Minke Whale Boing Calls

Listen to a Minke whale's "boing" call

Listen to a Minke whale's "boing" call

Fin whale downsweeps and backbeats

Listen to fin whale's downsweep and backbeat calls

Listen to fin whale's downsweep and backbeat calls

North Pacific right whale upcalls and gunshot calls

Listen to North Pacific right whale's upcall

Listen to North Pacific right whale's upcall

Listen to North Pacific right whale's gunshot call

Listen to North Pacific right whale's gunshot call

Ribbon seal calls

Listen to a ribbon seal's call

Listen to a ribbon seal's call

That list will continue to grow to include bearded seals, humpback whales, and more.

And when human analysts discover and describe new calls, INSTINCT can re-run previously analyzed data to search for them.

INSTINCT was recently deployed to investigate a call newly detected in the Bering Sea: the “low moan.” The AI program found more than 9,000 positive detections of this call while searching data from more than 15 mooring sites over 10 years. Using INSTINCT to identify this call type reduced the human workload by 96 percent: it took 3 months to complete 6 years worth of manual analysis!

Listen to the low moan of an unidentified species

Listen to the low moan of an unidentified species

"The challenge now is attributing this call type to species,” said Catherine Berchok, who leads the passive acoustics research team at the Marine Mammal Laboratory. “Finding out when and where these calls are occurring will help us solve this mystery. The speed with which INSTINCT produced this set of detections has allowed us to quickly adapt our monitoring plan to investigate the low moan call type further.”

Made in Alaska; Adaptable Across Oceans

INSTINCT was developed to identify Alaska marine mammals. But it is quickly adaptable to answer research questions across regions. Flexible and robust, INSTINCT can easily be retrained for different noise regimes and soundscapes.

“In the future I hope to continue to collaborate with other institutions and work on INSTINCT as part of an open source community,” Woodrich said. “We want to make it super accessible. We want to raise the floor, rather than the ceiling, to help get AI tools for everyone.”

In line with these goals, the team has made INSTINCT available as an open source project in a public repository.

“It has been really exciting to watch INSTINCT develop. We started out with no AI. Now it is making really cutting edge research possible,” Woodrich said. “INSTINCT has reached a capacity we only dreamed about years ago. Now we can say, we are ready for your data.”