The scientist who first named different species of killer whales on the West Coast of North America probably never saw one.

The Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution had invited Edward Drinker Cope to review a manuscript the Smithsonian had received from a California whaling captain named Charles Melville Scammon. A brilliant and ambitious young scientist from Pennsylvania, Cope would later become famous for naming more than 1,000 species and digging—and fighting over—dinosaur fossils across the American West.

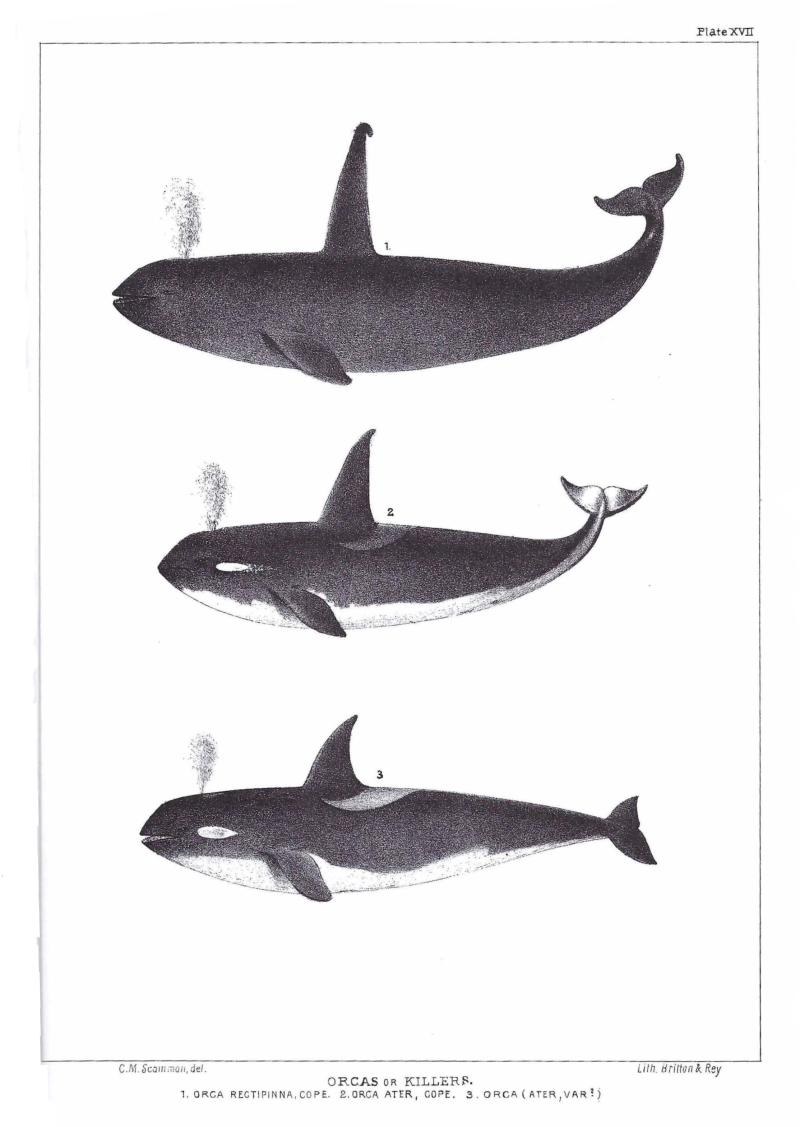

Scammon’s manuscript described several large marine mammals of the West Coast, calling killer whales “the wolves of the ocean,” which he said lived “by violence and plunder.” He identified two species, distinguishing them according to their dorsal fins. One species had tall, sharp dorsal fins, he observed; the other had shorter, blunt dorsal fins. He called them “high- and low-finned orcas.”

A team of NOAA Fisheries and university scientists published new research in Royal Society Open Science showing that West Coast resident and Bigg’s killer whales are different species. They are the first separately identified species of killer whales, breaking from the longstanding view that all killer whales belong to one worldwide species.

The father of species classification, Carl Linnaeus, in 1758 described killer whales as the single species Delphinus orca, later moved to the genus Orcinus. Other scientists have since claimed to have identified other species. However, the claims were sometimes based on only a single skeleton and lacked enough detail to be accepted by the science community. The descriptions of the two new species are based on hundreds of specimens, with detailed comparisons of genetic and other data.

To identify names for the new species, the scientists dug into the history of killer whale science on the Pacific Coast. They learned of lively personalities, evolving taxonomy, and missing skulls.

Cope Published Scammon’s Work

The Smithsonian may have intended Cope merely to review Scammon’s manuscript but Cope edited and then published the manuscript in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in 1869. He credited Scammon for the descriptions in the manuscript and listed himself as editor. But Cope never advised Scammon before publishing it, according to a 1986 biography of Scammon called, “Beyond the Lagoon.” While the descriptions of the species in the publication came from Scammon, the first species names for killer whales came from Cope.

He named one species Orca rectipinna (=Orcinus rectipinnus), a Latin term for “erect wing,” referring to the tall, sharp dorsal fin. He named the whales with shorter fins Orca ater (=Orcinus ater), Latin for black, referring to their dark color.

There is no record that Cope ever conducted research at sea or saw a live killer whale.

Cope and Scammon may, in many cases, have been distinguishing only male and female killer whales that they thought represented different species. Scientists now recognize that the largest male killer whales usually have the largest, sharpest dorsal fins. Lower and more blunt fins are typical for females and young males.

“The descriptions and illustrations make it clear that Scammon and Cope were not paying attention to the fine details that allow present-day biologists to distinguish the two species,” the new research paper reports. There is no sign, for instance, that they realized that Bigg’s killer whales (also called transients) prey on marine mammals while resident killer whales eat fish.

Scammon and Cope “were on the right track with two species, but they did not have all the details,” said Tom Jefferson, a research scientist at NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fisheries Science Center and coauthor of the new research separating resident and Bigg’s killer whales into different species. He probed archives and early accounts of Scammon’s whaling exploits for clues as to possible names.

Jefferson and his coauthors proposed to adopt Cope’s scientific names for the two species, assigning Orcinus ater for residents and Orcinus rectipinnus for Bigg’s killer whales. That means neither species will carry the ubiquitous name orca, derived from the worldwide species name, Orcinus orca.

Scammon was not pleased when he found out that Cope had edited and published his manuscript, in large part because he called Scammon a “United States Marine.” In fact, he had joined the Revenue Marine Cutter Service, a predecessor of the U.S. Coast Guard. Scammon sent letters to the Smithsonian, and Smithsonian Secretary Spencer Baird apologized for what he called “Cope’s absurd blunder,” according to the Scammon biography.

Whaling Across the Pacific

Scammon became an early authority on whales and other marine mammals while hunting them throughout the eastern Pacific Ocean.

He grew up in Maine with the fortuitous middle name “Melville,” although he was born before Herman Melville wrote his masterwork Moby Dick. Scammon sailed for the West Coast at 24, captaining a ship full of settlers seeking their fortune in the California Gold Rush around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. He then took up whaling, and turned out to be very good at it. While hunting whales, he observed and recorded their behavior. He discovered one of the large inland lagoons in Baja California, Mexico, where gray whales often give birth and nurse their calves. It is still known today as “Scammon’s Lagoon.”

Scammon killed and examined a 15-foot female killer whale in California thought to be a Bigg’s, as it had seal carcasses in its stomach. The whale's skull is believed to have been deposited at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. It was the obvious skull to be the “holotype” specimen used to define its species. Usually, the holotype is the first collected specimen of a species. However, the Academy’s entire collection including the skeleton and associated written records were destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire.

Since that first suspected Bigg’s skeleton was lost, Jefferson and his colleagues identified a stand-in skull from the Smithsonian Institution collected near San Francisco in 1966. It served as the “neotype,” a substitute that can define the species if the original is missing. They did the same for the resident species, Orcinus ater, with a skull collected in Puget Sound in 1967.

Despite the new scientific names, the scientists suspect that most people will continue to refer to them as residents and either transients or Bigg’s killer whales. They hope to engage with Northwest tribes to identify an appropriate common name for resident killer whales that recognizes their cultural importance to many West Coast tribes.