Alaska Fisheries Science Center Surveys in the Arctic: 2019 Preliminary Findings

We study marine ecosystems. Our research supports sustainable management and conservation of Alaska marine species.

We collect a variety of biological, ecological, and environmental data to learn about the health and size of populations of fish, crabs, whales, seals and other species in the key areas where they feed, breed, and grow.

Through long-term, consistent data collection during dedicated research surveys, we monitor trends in marine population abundance and changes in their distribution. This information helps Alaska Native and coastal communities, and resource managers better prepare and respond to changes in Alaska marine ecosystems to ensure sustainable use of marine resources, food security and coastal resiliency.

Ice Seal and Polar Bear Aerial Survey Test (Spring 2019)

Why were you working in the area?

NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s Marine Mammal Laboratory collects information to monitor the abundance of bearded, ringed, spotted, and ribbon seals. We are also studying their habitat needs, health and condition, diet, and the relationships between different populations of each species.

What did you do?

We tested a new camera system for surveys of marine mammals on sea ice. We wanted to demonstrate the effectiveness of an improved method for counting bearded and ringed seals and their main predator polar bears with airborne instruments.

Where did you go?

From May 5–25 we flew over parts of the southern Chukchi Sea using Kotzebue as our base, and parts of the Beaufort Sea from Deadhorse.

The new camera system was successful at producing high-quality color, infrared (IR or thermal) and ultraviolet (UV) images. Importantly the system aligns these images in a way that enables us to use powerful ‘machine learning’ methods for detecting and counting marine mammals. Without these advanced methods, the detection and counting processes are very labor intensive, time consuming and costly.

What are the impacts or implications?

With the improved camera system we will be able to survey more regularly and reliably than in the past. Better and more frequent surveys, in turn, will improve the information available to Alaska Native communities about the status of their traditional resources in the rapidly changing Arctic environment. With collected data NOAA Fisheries will also be able to monitor ice seal populations in accordance with U.S. federal laws.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We will share results at meetings of the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission in the Fall, 2019 and the Ice Seal Committee early in 2020. We also intend present results whenever we have opportunities to meet with communities and organizations as part of our general outreach and research coordination activities.

What are your future plans?

We hope to use the new aerial camera system to conduct a survey in spring of 2020 and 2021, subject to funding availability.

Contact

Adult Groundfish, Crab and Bottom-Dwelling Species Survey of Southeastern Bering Sea (Spring 2019)

Why were you working in the area?

The bottom trawl survey conducted in the southeastern Bering Sea shelf by the NOAA Fisheries-Alaska Fisheries Science Center represents one of the longest-running and comprehensive ecosystem monitoring surveys conducted in the U.S. The survey has been conducted annually since 1982 using the same survey design and methodology, making the results highly valuable for documenting and tracking change in the environment. Results from this survey are also used heavily in the monitoring and management of commercial fish and crab populations observed throughout the southeastern Bering Sea. These include walleye pollock, Pacific cod, red king crab, snow crab, and multiple flatfish species. Data was collected on the abundance, distribution patterns, size, age, and diet for numerous fish and crab species in addition to monitoring of physical environmental patterns, such as water temperature, salinity, and light. Water temperature results from this survey are used each year to document the extent of the cold pool, water near the seafloor with a temperature below 2°C, which has been shown to impact fish distribution patterns throughout the region.

What did you do?

From May 29–August 2, we conducted the standardized bottom trawl survey of the southeastern Bering Sea shelf ecosystem, using the same station grid and sampling methods that were established in 1982. The sampling grid used is made of up 20 nmi x 20 nmi grid cells that extend from Bristol Bay westward to a bottom depth of 200m and northwest of St. Matthew Island to the U.S – Russia Transboundary Line. Additional stations for higher density sampling exist near the Pribilof Islands and St. Matthew Island to aid in monitoring blue king crab populations. Overall, the survey contains 376 sampling stations. At each station, a 30 minute tow was conducted using our scientific research trawl, which samples fish and invertebrates (e.g., crabs) that are located near the seafloor. All organisms collected are identified to species and counted. Two vessels were used for the survey and sampling started in Bristol Bay and progressed to the west until the survey was completed. After the annual southeastern Bering Sea survey was completed, scientists moved northward to survey the 144 standard survey stations in the northern Bering Sea with a port call in Nome, AK.

Where did you go?

We conducted the survey in the southeastern Bering Sea shelf.

The region is outlined with sampling stations marked on the provided map.

What are your preliminary findings?

Seafloor water temperature results from the survey showed a similar trend as that observed in 2018 whereby the limited seasonal sea ice from the previous winter resulted in the second smallest cold pool observed over the time series. The smallest was in 2018 when there was effectively no cold pool observed. In 2019, 6.3 percent of the southeastern Bering Sea shelf survey area was within the cold pool, whereas, only 1.4 percent of the area was under cold pool conditions in 2018.In 2019, warmer than average water temperatures were also observed in Bristol Bay and throughout the inner shelf (water shallower than 50m) north from Nunivak Island to Norton Sound. For the first time, seafloor water temperatures over 8°C were observed in the region.

In 2019, pollock biomass (total estimated weight of fish in the surveyed area) in the southeastern Bering Sea was 5.46 million metric tons (mt), a 75 percent increase from 2018 (3.11 mmt). The abundance (total estimated number of fish in the surveyed area) increased 53 percent to 9.13 billion fish compared to 2018 (6.0 billion). The significant increase in abundance while the biomass is very similar is due to a large number of young fish that were observed in 2019 that were not there in 2018. The distribution of pollock was observed to be predominantly centered throughout the middle domain (region with a bottom depth between 50m and 100m) and extended to the north into the northern Bering Sea region. Pacific cod biomass was similar to 2018 at 517 thousand mt and like walleye pollock, Pacific cod abundance increased in the region. We observed a 112 percent increase to 527 million individuals due to a large increase in young fish. Bristol Bay red king crab had a 3 percent decline in biomass to 59 thousand mt. As observed in 2018, fish that prefer colder water conditions, such as Arctic cod, Bering flounder, and Alaska plaice showed declines in abundance from previous survey years. The biomass of yellowfin sole was slightly higher than 2018, at 2.01 mmt, and the distribution showed a continuation of the trend from recent years where the fish are observed farther offshore.

What are the research impacts or implications?

The continued lack of a substantial cold pool in the southeastern Bering Sea shelf has increased interest in research into the factors driving the redistribution of sub-Arctic species of fish. These include walleye pollock and Pacific cod. Without the presence of the cold pool to restrict their distribution, we observed a continued trend of these highly mobile species spreading out across the southeastern Bering Sea shelf. Observations of Pacific cod and walleye pollock also continue to be recorded in the northern Bering Sea survey area. Prior to the breakdown of the cold pool, this area was thought to have sparse or limited populations of these species.

Conversely, we saw a reduction in abundance of Arctic species that are thought to use the cold pool as a refuge in 2019. One such species, the Bering flounder was only observed near the area within the 2019 cold pool and only one Arctic cod was sampled during the survey. The decline in biomass of Bristol Bay red king crab may be, in part, due to the warmer than average water temperatures observed in Bristol Bay. In fact, very warm nearshore waters that extended from Bristol Bay and along the coast past Nunivak Island and north into Norton Sound had reduced catches of several species compared to historical surveys. One species that showed increased biomass within this warmer nearshore area was the purple-orange sea star.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We shared initial results for a few species of concern with several Bering Strait communities in the region and Alaska Native organizations and other groups in Nome, AK via conference calls. We plan to present the complete preliminary survey results to Bering Strait region communities and Alaska Native organizations in November in Nome, AK. Communication outreach includes working with University of Alaska, Fairbanks and Alaska Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program (MAP) agent to conduct in person meetings, radio and newspaper interviews, presentations, and conference calls.

What are your future plans?

Given the ecological and fishery significance of the southeastern Bering Sea region, plans to survey region again in 2020 are already underway.

Contact

Arctic Larval Fish and Plankton Community Survey (Summer 2019)

Why were you working in the area?

NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center and NOAA Research’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory collaborate as part of a multi-institutional, cross-disciplinary research team in the U.S. Arctic as part of the Distributed Biological Observatory. We collected oceanographic, environmental and biological data through a survey and from stationary moorings equipped with year round monitoring systems. We work with national and international organizations and Alaska Native communities to make observations from a suite of Arctic climate observatories.

What did you do?

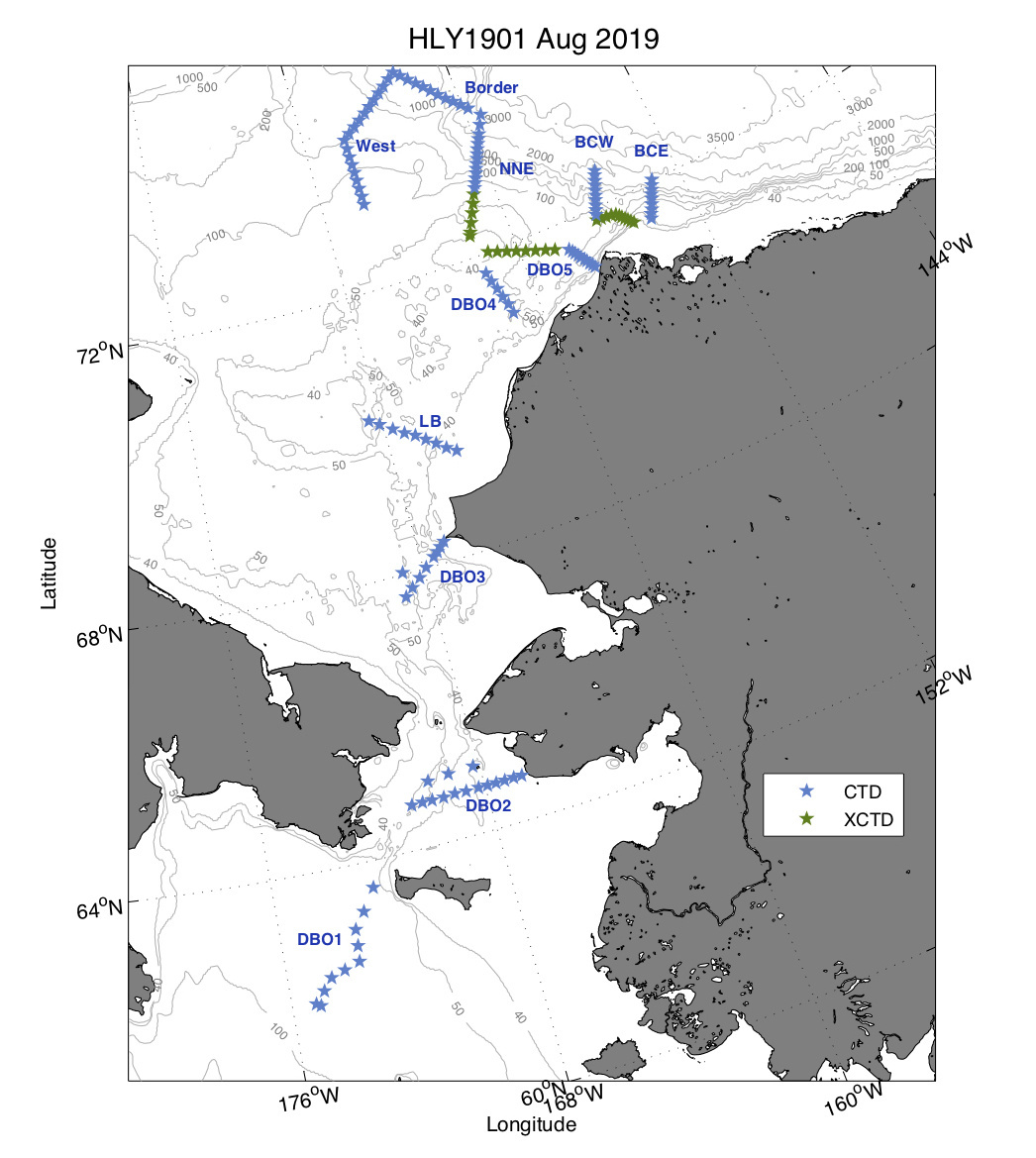

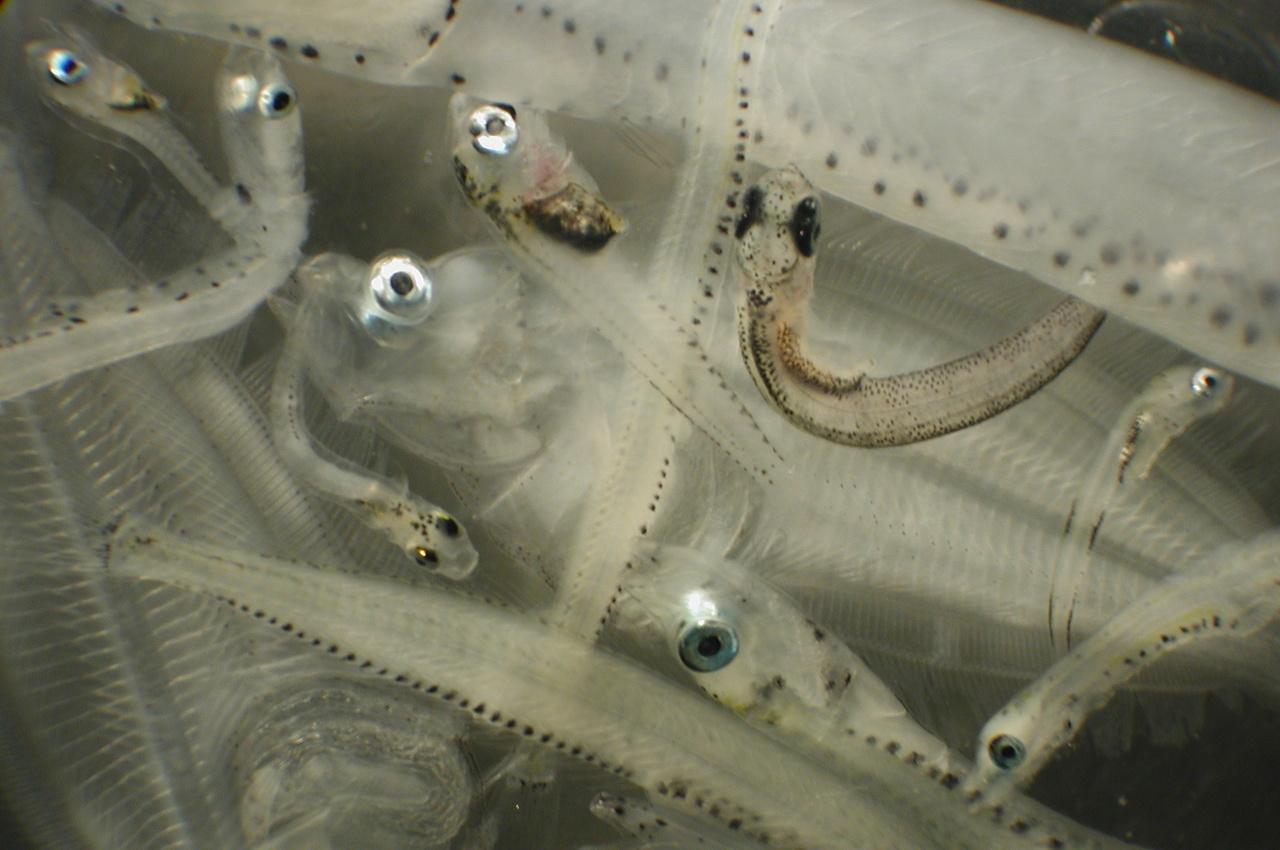

From August 4–23, we conducted a research survey aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy. Using observing systems, including the network known as the Distributed Biological Observatory (DBO), we measured the temperature of the water and air, presence and extent of sea ice, species abundance, biodiversity and production. We have been monitoring ocean changes every year since 2010 in areas of high productivity and biodiversity. We use derived data to document current physical state of the U.S. High Arctic (Chukchi and Beaufort Seas), examine the biological and ecological responses to that physical environment, and make comparisons with past observations. Physical oceanographers, biogeochemical scientists, benthic ecologists, and marine biologists collaborate to examine the ecosystem responses to climate variations. Alaska Fisheries Science Center scientists focus on examining production in the water column (phytoplankton, zooplankton, marine fish eggs, and larvae) to determine diversity and availability of prey at the base of the arctic food web.

Where did you go?

The surveys were conducted in selected areas (transects) across the Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf.

What are your preliminary findings?

Results to date indicate that the zooplankton community has been influenced by the loss of sea ice in the Chukchi Sea. The winter of 2018–2019 was a second record low sea ice year, and we noted that summer zooplankton production across all taxa sampled, small copepods, large copepods, and krill, were reduced. Data indicate a distinct lack of secondary production in the Chukchi Sea, possibly related to two consecutive record low sea ice winters and overall ocean warming.

What are the impacts or implications?

We will use survey results to better understand the processes involving ocean heat, circulation, and transport pathways into and out of the Arctic region. Collected data will also help us to understand the effects of loss of sea ice on lower trophic level biological resources (plankton). This is important information for Alaska Native communities since larval fish and plankton are prey for subsistence species. Data are also used in Ecosystem Status Reports for North Pacific Fishery Management Council.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We have been providing information to communities through in-person presentations, media engagement, and local discussions. Work from this survey was recently featured in the Nome Nugget and on KNOM Radio. We also gave a Strait Science seminar in Nome at the University of Alaska campus to share research findings and discuss implications with the community.

What are your future plans?

This is an annual survey, which will be conducted again in August 2020.

Contact

Aerial Survey of Bowhead Abundance (Summer 2019)

Why were you working in the area?

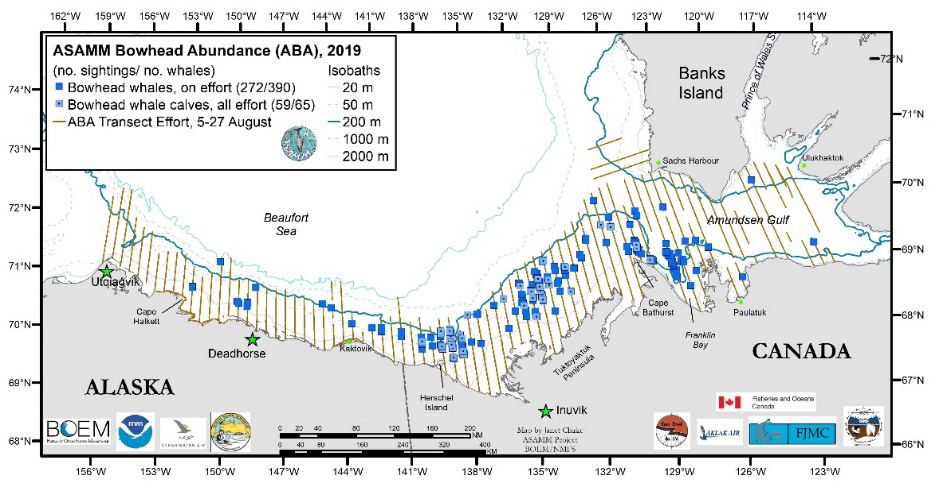

The International Whaling Commission requires a population abundance estimate to be submitted for the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort bowhead whale stock every 10 years. The next estimate is due in 2021. The ASAMM Bowhead Abundance project was developed to collect line-transect aerial survey data for use in a new abundance estimate. In the past, abundance estimates were derived from data collected during either ice-based bowhead whale censuses conducted as the whales rounded Point Barrow during their spring migration or from photo identification data. However, spring ice conditions are becoming increasingly hazardous to work from, and the photo identification analysis is time intensive. The study area for this survey was selected to encompass the majority of the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort bowhead population. August was chosen as the best time to conduct the surveys because it was anticipated that the study area would be relatively ice free, an important factor when conducting visual aerial surveys. The survey is an international collaboration among the NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, North Slope Borough, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Inuvialuit Game Council, and Fisheries Joint Management Council.

What did you do?

From August 5–27, we collected information via airplane to estimate the abundance of the Bering-Chukchi Beaufort stock of bowhead whales and to document the density, distribution, and behavior (including calving/pupping and feeding) of marine mammals (whales, ice-associated seals, and polar bears). We also collected supplementary imagery to be used for photo identification analyses and investigating scars from predation and entanglement.

Where did you go?

The surveys were conducted across the Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf.

What are your preliminary findings?

We flew 167 hrs. and 43,000 km. The Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf were mostly devoid of sea ice except for a tongue of ice that extended down the west side of Banks Island and scattered ice.

Bowhead whales and belugas were sighted throughout the study area. Most bowhead whales were in four general areas in the eastern Beaufort Sea:

- Franklin Bay in western Amundsen Gulf;

- Near Cape Bathurst;

- Off the Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula; and

- North of Herschel Island.

Far fewer bowhead whales were seen in the western Beaufort Sea, with sightings as far west as Cape Halkett. Sixty-five bowhead whale calves were seen. Belugas were sighted in high densities primarily in the eastern Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf, likely because that is where the survey transects extended into the deeper waters that belugas prefer.

Fifteen gray whales were sighted off the Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula; this is a rare sighting because gray whale range does not typically extend far into the Beaufort Sea. Most gray whales were feeding, and one calf was sighted. Polar bears were sighted on shore or barrier islands in the western Beaufort Sea. They were also observed on shore, on sea ice, or swimming near sea ice in the eastern Beaufort Sea. Three bears were at kill sites on sea ice.

What are the impacts or implications?

With the new abundance estimate the International Whaling Commission will be able to set the aboriginal subsistence quota for the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort bowhead whale stock. This is important because this stock is hunted for subsistence by Alaska Natives (and occasionally Russia). Results from the survey will also be used to provide an objective wide-area context for understanding marine mammal ecology in the United States and Canadian Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf. This will help inform management decisions and interpret results of other small-scale studies. Collected information will also be used for assessments of human impacts on marine mammal resources.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

Prior to survey, representatives from the North Slope Borough visited Alaskan and Canadian Native Communities in the U.S. and Canadian Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf to discuss the project with stakeholders. During spring, information about the survey was shared with Alaska Native communities in an outreach pamphlet that provided an overview of all of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s marine mammal research activities. During the field season, daily reports summarizing preliminary results were posted to the NOAA Fisheries’ website within 24–72 hrs. of completing flight. Data will be incorporated into the ASAMM historical database and posted to the ASAMM webpage on the NOAA Fisheries’ website. Preliminary survey results will be shared during the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, and Alaska Beluga Whale Committee meetings in autumn 2019.

What are your future plans?

We will use the data collected to estimate the population abundance of the Bering-Chukchi Beaufort bowhead whale population and will submit a report to the International Whaling Commission in Spring 2020.

Adult Groundfish, Crab and Bottom-Dwelling Species Survey of Northern Bering Sea (Summer 2019)

Why are you working in the area?

This Northern Bering Sea bottom trawl survey represents one component of NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s multi-faceted research plan to track environmental and ecological change throughout the Bering Sea. The project is called LOSI or Loss of Sea Ice. The scale and extent of fish and crab movements can vary from year to year in response to a variety of biological or environmental processes. In the past several years, under warmer than normal water temperatures, we have observed changes in the distribution and abundance of Arctic species and species typically found in the southeastern Bering Sea. For instance, the range of species like Pacific cod and pollock has extended beyond traditional survey boundaries. To generate accurate population estimates for these species and ensure sustainable resource management requires more comprehensive surveying of the entire Bering Sea. We collected data on the abundance, distribution patterns, length, age, and diet for numerous fish and crab species. Additional studies were conducted during the survey including tests for the presence of harmful algal bloom toxins in shellfish (at the request of Bering Strait communities), tagging studies for determining Pacific cod movement patterns, population genetics projects on several species of fish, snow crab reproduction, and predator-prey studies for several fish species.

What did you do?

From August 3–27, we conducted the full standardized bottom trawl survey of the northern Bering Sea ecosystem. We used the same station grid and sampling methods as in 2010 and 2017. This standard bottom trawl survey has a larger spatial extent (extends into Norton Sound) and higher sampling frequency (20 nautical mile grid) than the 2018 survey. In 2018, we conducted a smaller-scale Rapid Response Survey due to the unprecedented warm water conditions, which resulted in a historic reduction in the size of the spring cold pool. The cold pool forms from melted sea ice and creates a natural barrier for fish distribution between the northeastern and southeastern Bering Sea. After the annual southeastern Bering Sea survey was completed, scientists moved northward to survey the 144 standard survey stations in the northern Bering Sea with a port call in Nome, AK.

Where did you go?

We conducted the survey in the northern Bering Sea.

What are your preliminary findings?

As in 2017, another warm water year, we again saw large numbers of Pacific cod and pollock in the northern Bering Sea in 2019. The 2017 survey was the last time the standard survey was completed in the northern Bering Sea Region. Prior to 2017, the last time the northern Bering Sea had been fully surveyed by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center was in 2010. At that time, few pollock and Pacific cod were seen. Species collected in 2010 were primarily Arctic species (e.g., Arctic cod and saffron cod) and other bottom-dwelling (or benthic) species. In 2010 seasonal sea ice covered the northern Bering Sea in the winter and water temperatures were much colder in the summer.

In 2019, pollock biomass (total estimated weight of fish in the surveyed area) in the northern Bering Sea was 1.17 million metric tons (mt), which was 11 percent less than 2017 (1.32 million mt). The abundance (total estimated number of fish in the surveyed area) increased 59 percent to 2.9 billion fish compared to 2017 (1.8 billion). Much of this increase was due to more young fish in the area in 2019. As in 2017, the distribution of pollock was also most concentrated along the northernmost edge of the U.S. Russia Maritime Boundary near the Bering Strait and southwest of St. Lawrence Island. Pacific cod biomass in the northern Bering Sea increased from 283 thousand mt in 2017 to 368 thousand mt (+30 percent) in 2019. We also observed higher than expected abundances of juvenile pollock and Pacific cod (<20cm) in the northern Bering Sea.

Greenland turbot, Kamchatka flounder, and flathead sole, all deeper water species associated with the outer shelf (100-200 m), dispersed across the deepest areas (>50 m) of the northern Bering Sea shelf southwest of St. Lawrence Island. In the same area, arrowtooth flounder were observed for the first time in this new survey series. As observed in 2017, fish that prefer colder water conditions, such as Arctic cod, Bering flounder, and Alaska plaice showed declines in abundance from previous survey years. For instance, Arctic cod had a 99% decline in biomass between 2017 (4,000 mt) and 2019 (47 mt).

Note that since the resolution and spatial coverage was different for the 2018 Rapid Response survey, direct comparisons of results with the standard survey time series are difficult. However, results observed in 2018 appear to be similar to what was observed in 2019.based on all the stations sampled. In these stations, we also saw the biomass of jellyfish almost triple compared to 2017.

What are the research impacts or implications?

Findings from the 2019 northern Bering Sea survey again show that large numbers of sub-arctic species of fish (walleye pollock, Pacific cod, flathead sole, etc.) distributed throughout the region. Additionally, the increased catch of very young pollock and cod strengthens the hypothesis that these species are overwintering in the region during periods of low or limited ice coverage and spawning. Distributional patterns were different in 2017, 2018, and 2019 suggesting that environmental conditions and prey resources in the region are changing annually in the region, even with consistently warmer water conditions over last three years.

Questions still remain as to overall movement patterns of pollock and cod in the region, are fish freely moving between the southeastern Bering Sea and northern Bering Sea regions, migrating further north into the Chukchi Sea, crossing into Russian waters, or staying resident in the northern Bering Sea?

Our first answers to these questions will come from Pacific cod tagged during the survey and cooperative work with native fishermen from Savoonga, AK.

Low catch rates of arctic species, such as Arctic cod, were again observed, likely due to increased water temperature. Very high water temperatures were observed in Norton Sound and north of St. Lawrence Island, raising questions about the potential impact of sustained periods of warmer than average water temperatures on the benthic invertebrate community, much of which is not as mobile and able to avoid the changing conditions as large fish or crabs.

The data we collect complements the Traditional Knowledge of Alaska Native hunters and fishers providing a more complete picture of bottom-dwelling species across the entire eastern Bering Sea shelf to help us better understand the effects of a changing marine environment and diminishing annual sea ice on marine food webs. The co-sharing of knowledge with community leaders during in-person meetings and conference calls has greatly aided in the development of our science questions and understanding of environmental change in the region.

These results also have important implications regarding food security for Alaska Native communities and the sustainable management of commercial fish and crab stocks throughout the Bering Sea.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We shared initial results for a few species of concern with several Bering Strait communities in the region and Alaska Native organizations and other groups in Nome, AK via conference calls. We plan to present the complete preliminary survey results to Bering Strait region communities and Alaska Native organizations in November in Nome, AK. Communication outreach includes working with University of Alaska, Fairbanks and Alaska Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program (MAP) agent to conduct in person meetings, radio and newspaper interviews, presentations, and conference calls. Information will also be shared during the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission annual meeting in October.

What are your future plans?

Given the ecological importance of the northern Bering Sea region, sustained warming conditions and rapid loss of seasonal sea ice, discussions are already underway to formulate a survey plan to return in August 2020.

Contact

Arctic Ecosystem Assessment (Summer 2019)

Why are you working in the area?

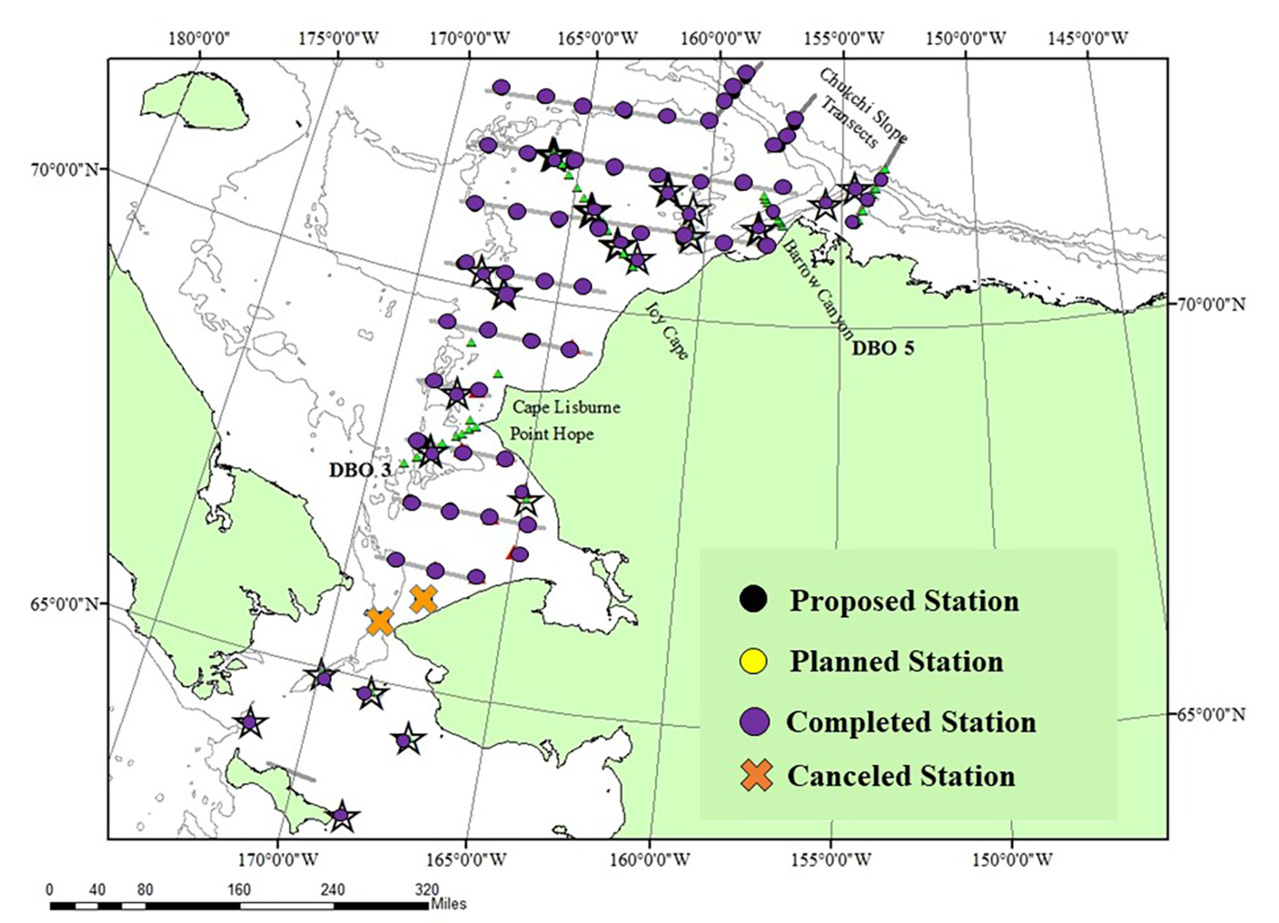

NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center conducts fisheries oceanographic surveys to gather needed data to understand how loss of seasonal sea ice in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas impacts the food web (physical environment to humans). Funding for the survey was provided by the North Pacific Research Board and the Bureaus of Ocean and Energy Management. We provide information on the sea temperatures, the food web, and key fish in the region such as Arctic and saffron cod, salmon, and other forage fish. We partner with other agencies and universities to gather information on seabird species composition and distribution, the fitness of fish, and to model fish distribution. This is the fourth integrated ecosystem survey conducted along the Chukchi Shelf. Other years include 2012, 2013, and 2017. This year, the survey was conducted aboard a charter vessel, Ocean Starr.

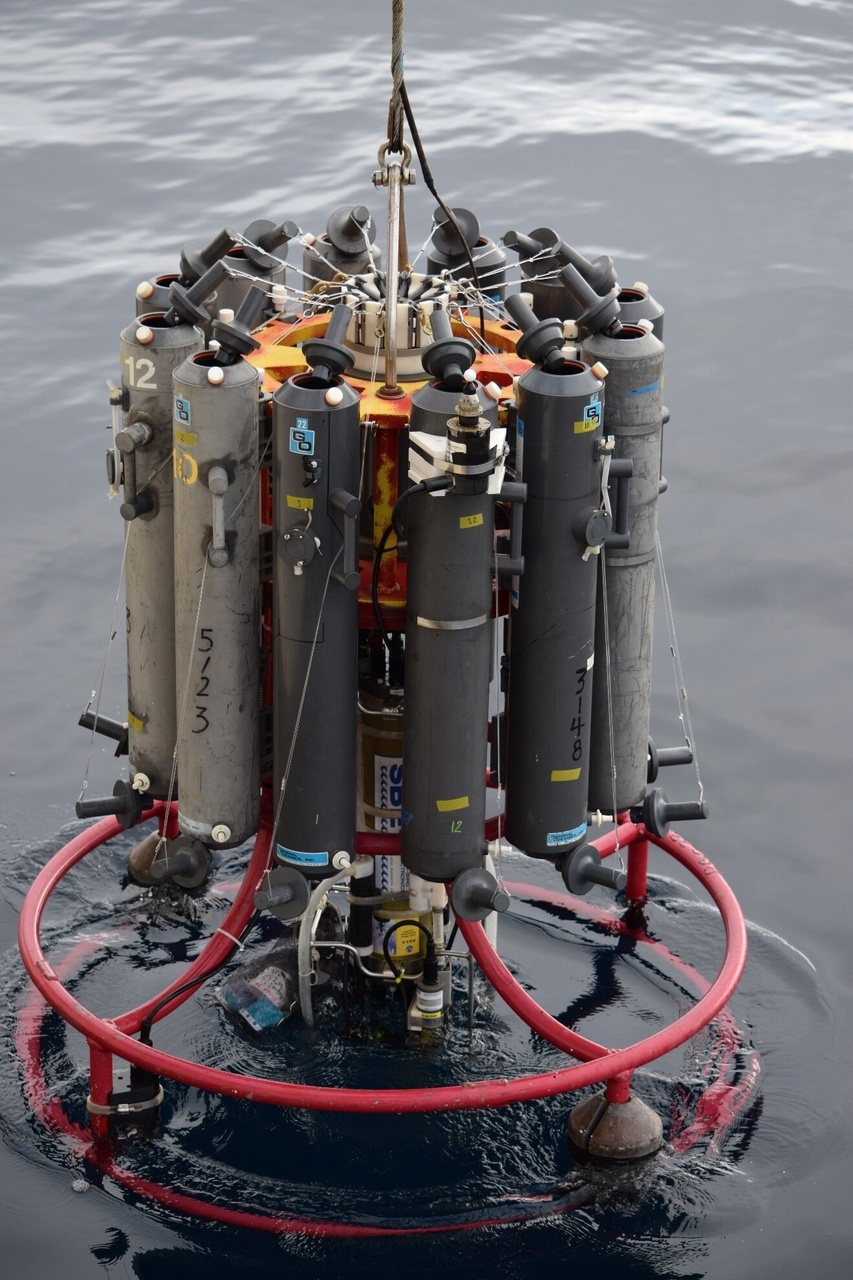

A carousel containing instruments and bottles to collect water column data from surface to near bottom depths on sea temperature, salinity, light, amount and species composition of chlorophyll, nutrients, and the presence of harmful algae.

What did you do?

From August 1 to October 1, we conducted an integrated ecosystem survey (physical environment, nutrients, phytoplankton, zooplankton, fish, and seabirds).

Where did you go?

We took samples at stations (purple dots) within the Chukchi and Beaufort seas between 65°N and 72.5°N. Mooring deployment and recovery occurred at the stars on the map. Data on sea temperature and salinity was also collected along transects (green triangles).

What are your preliminary findings?

Overall sea temperatures in on the Chukchi Sea shelf were warm and varied between 5.3C (41.5F) to 10.9C (52F). We note that zooplankton abundances were very low compared to previous years. Age 0 Arctic cod dominated the midwater catch, however the acoustic backscatter for these fish indicated fewer fish in the region when compared with 2017. Of note were the large numbers of age 0 walleye Pollock caught along the 70.25N transect as well as in the southern Chukchi Sea. Invertebrates including notched brittle stars, snow crab, northern nutclam, basket stars and common mud stars dominated the catches on the ocean floor. There were six dead seabirds seen including two horned puffins, a black-legged kittiwake, a common murre, and two unidentified bird species.

What are the research impacts or implications?

Data from our surveys help us understand how reductions in Arctic sea ice and warming of seasonal sea temperatures affect the food web (small plant life to humans) of the Chukchi Sea ecosystem.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We shared results from the survey via KNOM radio and the Nome Nugget. We also gave a Strait Science presentation in Nome, AK at the University of Alaska campus on September 16. A survey report will be provided to communities by mid-November, 2019.

Learn more about the survey and the Arctic Integrated Ecosystem Research Program

What are your future plans?

This ends the field sampling for the North Pacific Research Board/BOEM Arctic Integrated Ecosystem Research Program. The scientists will continue to analyze data and consult with community experts within the program to better understand how loss of seasonal sea ice in the Arctic will affect the food web and communities.

Contact

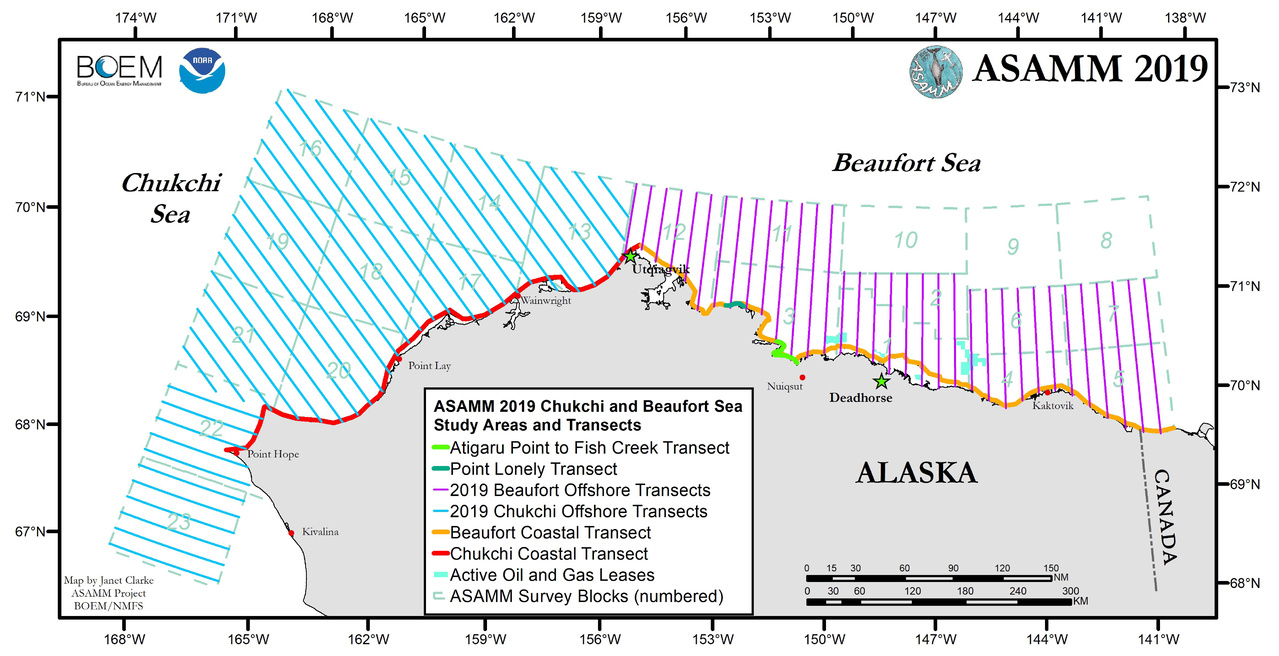

Aerial Survey of Arctic Marine Mammals (Summer & Fall 2019)

Why were you working in the area?

The Aerial Survey of Arctic Marine Mammals (ASAMM) project flies surveys during summer and fall each year in the eastern Chukchi and western Beaufort seas. This work is funded under an Interagency Agreement between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The surveys document the distribution, relative abundance, and behavior of bowhead whales, gray whales, beluga whales, and other marine mammals in areas of potential oil and gas seismic surveying, drilling, construction, and production activities.

What did you do?

From July 1 to October 31, we collected visual sighting data during the line-transect aerial surveys in various areas over time. This information is instrumental in describing the annual autumn migration of bowhead whales across the U.S. Arctic. We also collected aerial imagery that is used for photo-identification and body condition assessment of large whales, and to document scars from predation and entanglement.

Where did you go?

The surveys are conducted in the eastern Chukchi and western Beaufort seas.

What are your preliminary findings?

Through the first three months of the 2019 season, We flew over 300 hours and 80,000 km. The study area was devoid of sea ice by early August. Bowhead whale occurrence in the western Beaufort Sea was reduced and farther offshore in September 2019 than in September of any previous year dating back to 1979. It is unknown whether bowhead whales are staying in the eastern Beaufort Sea later into fall than normal, delaying the autumn migration, or are passing through the Beaufort Sea farther offshore, outside of the ASAMM study area.

Gray whales were observed primarily in two areas: an area rich in bottom-dwelling prey in the southcentral Chukchi Sea, and south of Hanna Shoal in the northeastern Chukchi Sea. Nearly all gray whales were actively feeding. We are participating in efforts to document gray whale body condition to assist with an international investigation of the gray whale Unusual Mortality Event that NOAA declared in 2019.

Fin whales were observed farther north than we had previously documented in the Chukchi Sea; these may be the farthest north fin whale sightings in the Pacific Arctic. Humpback whales and minke whales were sighted in the vicinity of these northern fin whales. Fin, humpback, and minke whales were documented in the southcentral Chukchi Sea, similar to recent years. Killer whales were sighted 90 km west of Utqiaġvik.

Walruses started hauling out on a barrier island near the village of Pt. Lay in July. This is the earliest walruses have been documented on shore near Pt. Lay. We documented the size and scope of the haulout on 3 days in August and September. Due to the early sea ice retreat in the Beaufort Sea in summer 2019, polar bears were sighted on shore in greater numbers and earlier in the season than previous years.

What are the impacts or implications?

Results are used to provide near real-time data and derived products, such as graphical data summaries, on marine mammals and environmental conditions in the U.S. Arctic to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and NOAA Fisheries. We also provide information on marine mammal abundance and distribution to Alaska Native communities for use in management of subsistence hunts and assessments of human impacts on marine mammal resources. Collected data provide an objective wide-area context for understanding marine mammal ecology in the U.S. Arctic to help inform management decisions and interpret results of other small-scale studies.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

During spring, information about upcoming ASAMM surveys are shared with Alaska Native communities in an outreach pamphlet that provides an overview of all of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s marine mammal research activities. During the field season, daily reports summarizing preliminary survey results are posted to the NOAA Fisheries’ website within 24–72 hrs. of completing each flight. We communicate flight plans with the village of Point Lay if survey flights are expected to pass offshore of the village when walruses are hauled out in mass. The ASAMM historical database and additional results are available on the NOAA Fisheries’ website. Preliminary survey results will also be shared during the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission meeting in Anchorage in October.

What are your future plans?

Contact

Janet Clarke (jclarke9@uw.edu)

Catherine Coon (catherine.coon@boem.gov)

Surface/Mid-Water Column Community Survey of Bering Sea (Summer & Fall 2019)

Why are you working in the area?

This is a multi-disciplinary fisheries and oceanographic survey in the northern Bering Sea. Its goal is to improve understanding of the status of pelagic fish resources and the impact of loss of Arctic sea ice on the eastern Bering Sea ecosystem. This survey has been conducted on an annual basis since 2002. Currently it is being conducted in collaboration with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Other university and agency scientists also have been an integral part in the research conducted over the last 17 years.

What did you do?

We conducted the 2019 northern Bering Sea surface trawl survey was conducted aboard the F/V Northwest Explorer from Aug 27 to Sep 20. Principal funding support for the survey was provided by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, the Alaska Sustainable Salmon Fund, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Additional funding support was provided by Alaska Pacific University, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. We collected data on the physical and biological characteristics of the northern Bering Sea shelf, including: temperature and salinity data, water collections for nutrient and phytoplankton samples, bongo net samples of zooplankton, benthic grabs, surface trawl data and samples of pelagic fish, and observations of seabird distribution and abundance.

Where did you go?

What are your preliminary findings?

Average sea temperatures were approximately 2.5- 3.0 degrees above average, zooplankton estimates were lower than average, the size of juvenile fish were above average, and there did not appear to be an obvious decline in the abundance of zooplankton prey. Juvenile herring, pink salmon, and sockeye salmon abundance levels were well above average, but the abundance of juvenile Chinook salmon was below average for the second year in a row. Future laboratory analysis of specimens collected during the survey will provide insight into the diet, condition, and genetic origins of pelagic fish in the northern Bering Sea.

What are the research impacts or implications?

Juvenile Chinook salmon has been a focal species for this survey due to the significant declines in their production, their importance to subsistence fisheries, international fisheries management, and management of bycatch in the Bering Sea pollock fisheries. Juvenile Chinook salmon abundance is significantly related to adult returns to the Yukon River and is an important component in the stock assessment models that define run size outlooks for Yukon River Chinook salmon.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

What are your future plans?

We hope to secure funding to continue this survey in 2020 and into the future.

Contact

Plankton, Larval Fish and Oceanographic Surveys in Bering Sea (Spring & Fall 2019)

Why were you working in the area?

NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center and NOAA Research’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory collaborate in this bi-annual (EcoFOCI) survey. We collected oceanographic, environmental and biological data through a survey and from stationary moorings equipped with year round monitoring systems. Through this bi-annual survey we monitor ice conditions, oceanographic characteristics, zooplankton, larval fish, distribution, and abundance in Spring and Fall.

What did you do?

In Late May and Late September, we conduct research surveys aboard the NOAA Research Vessel Oscar Dyson. During the spring survey we take out the subsurface moorings and deploy surface moorings, we also use various equipment (e.g., CTDs and bongo nets) to collect data on oceanographic conditions and sample zooplankton as far north on the 70-m as ice permits. During the fall survey we retrieve the surface moorings and deploy the subsurface moorings. We also collect water and zooplankton samples. Our focus is on examining production in the water column (phytoplankton, zooplankton, marine fish eggs, and larvae) to determine diversity and availability of prey at the base of the Bering Sea food web. Opportunistic information is collected on marine mammals as well.

Where did you go?

The surveys are conducted along the 70-m isobath. We also look at the flow through Unimak Pass and through the Bering Canyon water once it’s on the shelf (along the 50 m isobath, up the 100 or 200 m isobaths, etc.

What are your preliminary findings?

We observed moderately low abundances of certain plankton, large copepods >2 mm, and high abundances of small copepod < 2 mm in Spring along the 70m isobaths. High abundances of small copepods in a warm year is not unusual. As in the warm springs of 2015 and 2018 we also observed very low levels of krill (Small euphausiids <15 mm).

What are the impacts or implications?

Two key areas of interest in this survey are Unimak Pass and Bering Canyon. Unimak Pass is the main point of shelf connectivity between Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea for water and marine animals. It is also a cross trophic hot spot (from plankton up to whales). Bering Canyon is important conduit of slope and basin flow and animals up onto the continental shelf. Data are used to inform ecosystem and climate models.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We gave radio and newspaper interviews and a Strait Science presentation at the University of Alaska campus in Nome, AK.

What are your future plans?

We are hoping to conduct this survey again from April 29–May 11 and from September 18–30, 2020.

Contact

Phyllis Stabeno (phyllis.stabeno@noaa.gov)

Passive Acoustic Whale Monitoring (Ongoing)

Why are you working in the area?

The Arctic is changing. Sea ice is diminishing, human impacts are increasing, and subarctic species are intruding; more complete information is needed on the year-round presence of Arctic marine mammals and their acoustic communications. Passive acoustic monitoring is the best tool for large-scale, year-round assessment of marine mammal spatio-temporal occurrence, and ambient noise levels, especially in the harsh conditions of the enormous Alaska Region. We have been partnering with NOAA Research’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab (PMEL) since 2007 to deploy approximately 20 year-round passive acoustic recorder moorings (mostly BOEM-funded, but recently NAVY and NOAA funded) in the Bering, Beaufort, and Chukchi Seas in close proximity to oceanographic moorings.

What did you do?

We participated on three separate research surveys to recover and redeploy our long-term moorings (including the Arctic Integrated Ecosystem Survey previously mentioned). Data were extracted from the recovered instruments and will be analyzed (as funding permits) this winter in Seattle.

Where did you go?

Moorings were recovered and/or deployed at 19 sites in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas, and in the Gulf of Alaska.

What are your preliminary findings?

We are just beginning to analyze data retrieved this year, so no findings are available. However differences have been seen in the timing of Arctic and subarctic species movements between the Bering and Chukchi Seas in the past couple of years. These differences appear to be related to sea ice formation and retreat.

What are the research impacts or implications?

Long-term data on marine mammal spatio-temporal occurrence are critical for establishing baseline information that can be used for decision-making in Alaskan waters. In addition, marine mammals are excellent proxies for ecosystem change, since they respond to shifts in abundance and distribution of large zooplankton and small fish taxa.

How and when will you be sharing information with communities?

We no longer have our own dedicated research surveys, therefore information on our research is included in the outreach and communication efforts by the Chief Scientists on these surveys.

What are your future plans?

We hope to redeploy all moorings again in 2020.