Cook Inlet beluga whale.

NOAA Fisheries has published a new report in Marine Fisheries Review. In it, a team of scientists from NOAA Fisheries, the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, University of Washington, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Oceanwide Science Institute and a teacher from Mount Edgecumbe High School in Sitka consider the potential effects of ocean noise. Noise was identified as a threat of high concern in the 2016 Cook Inlet Beluga Whale Recovery Plan.

The Importance of Hearing and Communication in the Beluga Community

Belugas have a well-developed sense of hearing. They can hear sounds within the range of 1.2 to 120 kHz, with the greatest sensitivity between 10 and 75 kHz. For comparison, humans’ hearing range is 0.02 to 20 kHz—five times smaller.

This keen sense of hearing is important because belugas are big communicators. In fact, belugas often are referred to as "canaries of the sea" for their vast repertoire of sounds, including whistles, squeals, moos, chirps, and clicks. They use these sounds to find each other in the murky waters of Cook Inlet.

When feeding, belugas use echolocation to find food, emitting a sequence of impulsive sound signals, termed clicks. Once a beluga whale receives an echo from its target prey, the beluga is able to interpret distance to that prey and its location.

Pervasive noise throughout the year and in different locations in Cook Inlet could inhibit beluga whales’ ability to hear, communicate, and find food.

How a Beluga Whale Hears

• Sounds are received by the lower jaw and transmitted towards the middle ear.

• In toothed whales, the lower jawbone is broad with a cavity at its base, which projects towards the place where it joins the cranium, next to the middle ear.

• A fatty deposit, with optimal sound transmission characteristics, along the lower jaw and inside this small cavity connects to the middle ear.

• Toothed whales also possess a small external auditory canal a few centimeters behind their eyes, and each hole communicates with an external auditory conduit and an eardrum. Whether these organs are functional or simply vestigial is unknown.

Cook Inlet beluga whale.

Natural ambient noise is elevated in some portions of the upper Inlet during peak tidal current periods. Scientists suspect that this occasional natural noise is probably only affecting belugas’ lower hearing range. It probably is not inhibiting their activities because they are accustomed to this natural background noise.

However, Cook Inlet is surrounded by the most populated region of Alaska. Scientists believe noise from a variety of human activities may be a concern for the whales’ recovery.

NOAA Fisheries began conducting acoustic research on beluga whales in Cook Inlet in 2008. Scientists anchored moorings equipped with acoustic monitoring devices for five years at 10 different locations in upper, mid, and lower Cook Inlet. More than 8,700 hours of acoustic recordings from July 2008 to May 2013 were analyzed to describe underwater human-generated noise in Cook Inlet and evaluate the potential impact on beluga whales. This represents the most complete set of sound recordings for this waterway to date.

“Over the course of our study, we did not find a single 24-hour-period without the presence of human-generated noise in any of the monitored locations and months,” said Manuel Castellote, research affiliate at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

Scientists looked at the amount, diversity, and amplitude (loudness) of the noise that beluga whales are likely exposed to when they are travelling within the monitored areas.

“We determined that, at a minimum, several of the noise sources identified will likely affect beluga behavior. In some situations, depending on how close the whale is to the sound source, there also is the possibility of acoustic injury but more research is needed to fully evaluate this,” said Castellote.

The research team identified 13 sources of human-generated noise. These include ship traffic and dredging, to noise from aircraft, outboard engines, pile driving, and various machinery.

Noise from commercial ships was widespread and at elevated levels. In beluga whale studies in the St. Lawrence estuary, Canadian scientists estimated that ship noise between 102.1 – 114.1 dB had the potential to reduce beluga communication, and their echolocation range was reduced by up to 85% compared to natural noise conditions. In the Castellote et al. study in Cook Inlet, more than 79% of the sound clips of commercial ship noise were above 114.1 dB. Thus the potential communication and echolocation range reduction for Cook Inlet belugas is even more extreme than in the Canadian estuary.

At Cairn Point, close to the Port of Anchorage, the loudness and duration of commercial ship and machinery noise were most concentrated. Noise was present in all recordings, with the highest levels around August. Scientists find this particularly troubling because relatively large numbers of belugas are known to move regularly through this area, particularly during the summer months, to access important foraging grounds.

Efforts Continue to Study the Impact of Noise on Beluga Whales

Scientists stressed that future research should include additional monitoring locations and months sampled and efforts to learn more about unknown sources of human-generated noise, which were documented in previous studies. They identified the following areas for further research:

- Commercial shipping impacts in critical areas and periods need further study to identify new management approaches to reduce belugas’ noise exposure.

- Knik Arm is an important habitat for belugas and a corridor to access major foraging areas. In particular, lower Knik Arm is a beluga concentration area during the ice-free season when human activities are most intense. Castellote and others are currently involved in a new study to better understand the potential negative effects (e.g., displacement, abandonment) from noise exposure in foraging areas affected by human noise.

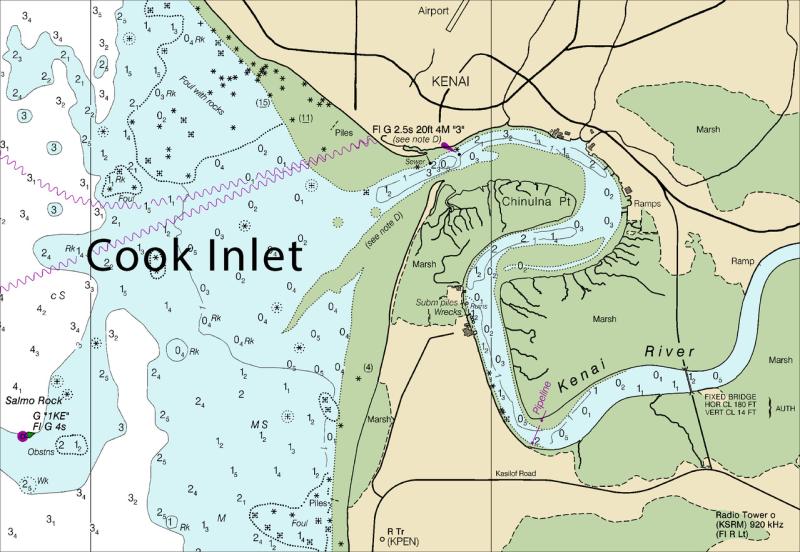

- Historically, the Kenai River was intensely used by belugas from April to November (the salmon runs peak June to October). Currently however, belugas appear to prefer February to April for foraging in the Kenai River.

- Noise from activities occurring at different times of year and in different areas warrants additional study when multiple projects are co-occurring to help understand the cumulative impacts on belugas.