"It worked!" he says quietly while walking into the laboratory with an ear-to-ear grin and his characteristic two-thumbs up. "It survived the test."

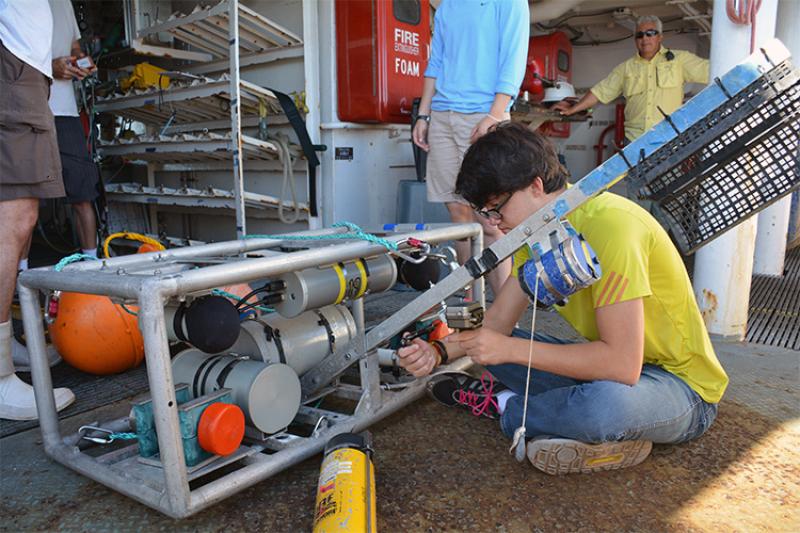

It's late afternoon in October and we are in the dry laboratory of the NOAA Ship Hi'ialakai white room with a perimeter of computer workstations and a large, chest-high table in the center for group meetings. After being out on the water all day, the crew from one of the small boats has just returned to the Hi'ialakai with exciting news: Christopher Lindsay's newly created PVC-tube camera housing has survived a critical depth test of 122 meters (401 feet).

Lindsay, a sixteen-year-old intern with NOAA Fisheries in the Pacific Islands Region, has spent the summer designing his apparatus to provide scientists with a cheap alternative to the expensive underwater camera equipment used in some marine biology research.

"As long as nothing breaks, I think [this project was] a success," he later tells me when we sit down for a debrief. "I was able to test the housings that I needed to the PVC housings down to their maximum depth, so that was good."

Right now, however, there is no time for sitting. As quickly as Lindsay entered the dry lab with his soft exclamation, he exited the room out another door, off to double-check his camera housing for any leaks that would preclude its use in real experiments.

Though he's normally quiet and reserved, Lindsay's excitement is palpable at this moment, and it's really no wonder the triumph of the test could spell even bigger things for the already surprisingly accomplished 'Iolani School student, such as an enduring partnership with NOAA Fisheries.

History of Achievements

Lindsay is no stranger to success and accolades, having won numerous prizes in everything from history bowls to essay contests to science fairs.

He's even published in the scientific literature.

Last year, Lindsay co-authored a scientific paper in the acclaimed journal Astronomy & Astrophysics that detailed the discovery and confirmation of an extrasolar planet. He previously presented this research at a national-level science fair, as the only high school freshman (at the time) from Hawai'i to qualify for the competition.

Lindsay's internship with NOAA Fisheries is also tied to the science fair world in early 2015, he won it at the Hawai'i State Science and Engineering Fair (HSSEF).

"He seems to have a dream and a vision," says NOAA Fisheries science operations logistics leader Chris Demarke, who worked with Lindsay during his NOAA internship. "He's impressed a lot of people and is somebody we really want to help along the way."

Lindsay is also no stranger to NOAA or awards from the organization. At the 2011 HSSEF, for instance, he won the NOAA "Discover Your World" award, which amounted to a trip to the Big Island's Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, Mauna Kea Observatory, 'Imiloa Astronomy Center, and Mokupāpapa Discovery Center.

Despite this prize and others at science fairs before, Lindsay describes the NOAA internship award as his "dream prize," though it's not difficult to imagine why.

The internship, after all, would provide Lindsay with the opportunity, financial support, and mentorship to continue his unique research on developing an inexpensive underwater camera system to study Hawai'i marine biota living on discarded munitions — research that was borne out of a completely separate project.

Nabbing the Dream Prize

In early 2014, after a rigorous selection process, a committee at 'Iolani School chose Lindsay and four other students to participate in a project with scientists at the University of Hawai'i (UH), a project the team would later present at the Japan Super Science Fair in Kyoto and Lindsay would later write about in a paper for the Marine Technology Society Journal (his second research article).

For the venture, Lindsay and his colleagues developed a low-cost (less than $1,000) underwater time-lapse photography system to investigate whether the whitetip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus) in Hawai'i poses any danger to the public (their conclusion: it doesn't).

The team, which Lindsay led, developed a hardy camera system made up of a Raspberry Pian inexpensive, power-efficient, credit-card-size computer often used to teach students programming skills and associated camera; a simple light system consisting of 66 white LED lights soldered together; one D-cell battery pack to power the lights and another for the computer and camera; two half-inch (1.3-centimeter) thick aluminum housings, each with a see-through acrylic cap; and a waterproof cable to connect the two parts of the system together.

"Our mentor that we got for that project was a person named Margo Edwards, who saw that I was very interested in this underwater photography," Lindsay says in his unexpectedly deep voice. Edwards, a research scientist at UH, leads the Hawai'i Undersea Military Munitions Assessment (HUMMA), a program that is looking at the potential environmental and human health risk posed by munitions that were dumped into the waters off Pearl Harbor after World War II. "[She] sort of asked me if I wanted to help out with their research. And I wanted to, obviously."

In 2012, HUMMA sent down two time-lapse camera systems one of which was developed by former 'Iolani School students to the munitions, and the project found numerous animals living on the weapons, including a newly discovered species of starfish called Brisingenes margoae (named after Edwards). The scientists then wanted to see these animals in their natural habitat, but the camera systems they were using were large, power hungry, and expensive, using hacked point-and-shoot-cameras.

But Lindsay's Raspberry Pi system was the complete opposite.

An ROV dropped Lindsay's camera system off Pearl Harbor near a natural rock formation about 550 meters (1800 feet) deep. After 4.5 days (about 50 percent longer than HUMMA's previous camera deployments) in the deep, Lindsay's camera took 6,048 images of various marine life, including B. margoae, Heterocarpus shrimp (commonly used in shrimp tempura in Hawai'i), and rattail fish, among others.

Building a cheap camera system from scratch that works well underwater is a remarkable achievement, comments Demarke, adding that "getting camera systems and electricity and everything to work well underwater is often an exercise in futility."

For his science fair project, Lindsay quantitatively and qualitatively compared the data from his images with those from the 2012 HUMMA deployments, and found very similar species in the two types of footage. "So it's safe to say these munitions are now functioning as artificial habitats for the animals living at that depth," he explains.

NOAA Fisheries awarded Lindsay its prestigious internship prize one of only two NOAA internships offered at the HSSEF that year for his intriguing marine science research, which has clear applications to the organization's bottomfish population assessment research.

Lindsay eagerly accepted the internship award.

"Because of those prizes I won before, I definitely knew what NOAA was and what NOAA was doing," Lindsay says. "I was very interested in doing what they do."

Unbeknown to Lindsay at the time, the NOAA Fisheries internship would, in fact, give him first-hand experience of what life as a NOAA scientist is really like.

Tune in again for the second part of Success, 100 Meters Below to learn about intern Christopher Lindsay's work with NOAA Fisheries and the mutually beneficial relationship between the two.

Read the second part of this story here.

Story by Joseph Bennington-Castro, PIRO Senior Science Writer