NOAA and partners continue to care for the female Hawaiian monk seal RO28/Pōhaku, who is suffering from toxoplasmosis, a disease caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. On February 19, 2020, the U.S. Coast Guard transported Pōhaku to The Marine Mammal Center’s Ke Kai Ola facility on Hawaiʻi Island after she spent almost a month at NOAA’s facility on Oʻahu. Before infecting Pōhaku, toxoplasmosis, which is spread into the environment via cat feces, killed at least 11 monk seals in the last two decades. Pōhaku has now survived nearly a month in our care and shown gradual improvement. But we remain cautious in our optimism, especially as we must now report that the toxoplasmosis death toll has risen to 12 seals.

Shortly after NOAA rescued Pōhaku, a young male monk seal (RKC1) was found dead on the windward side of Oʻahu. Results of the postmortem examination showed that he died after being exposed to T. gondii, a microscopic parasite found in cat feces that causes toxoplasmosis. RKC1, nicknamed Sole by the residents of Kalaupapa, Molokaʻi, had been rescued earlier in his life, in 2018, at 3 weeks old. Kalaupapa is a special place for monk seals because its quiet beaches are home to many newborn pups each year. Sole was rehabilitated at Ke Kai Ola because he was weaned from his nursing mother at an early age. He would likely not have survived long without intervention.

During his time at Ke Kai Ola he gained the weight necessary to survive on his own, and was then released at his birth site. Once back in the wild, he spent a few weeks exploring the Kalaupapa peninsula with other weaned pups, before making the journey to Oʻahu. Sole remained on Oʻahu, where he spent his time around the windward islets and rocky shorelines, highly elusive and rarely seen. Read more about Sole's rehabilitation story at Ke Kai Ola.

Like many cases of toxoplasmosis in monk seals, Sole’s death came without warning. NOAA was able to conduct a thorough post-mortem examination, thanks to prompt reporting by a member of the public. The results definitively showed that he died from toxoplasmosis. This means that the disease was solely responsible for his death—the T. gondii organisms were directly associated with severe inflammation and dysfunction in multiple organs. Sole was otherwise healthy and in good condition, and it appears that the infection was recent, aggressive, and rapid. Unfortunately, these are common findings for most Hawaiian monk seals affected by toxoplasmosis.

Sole’s death underscores the need for preventative action against this disease. There is no vaccine for this disease and it is extremely difficult to treat. The best way to help monk seals is by stopping the spread of toxoplasmosis. You can help by keeping your cats indoors so they don’t defecate T. gondii into the environment.

What Is Toxoplasmosis and How Does It Impact Monk Seals

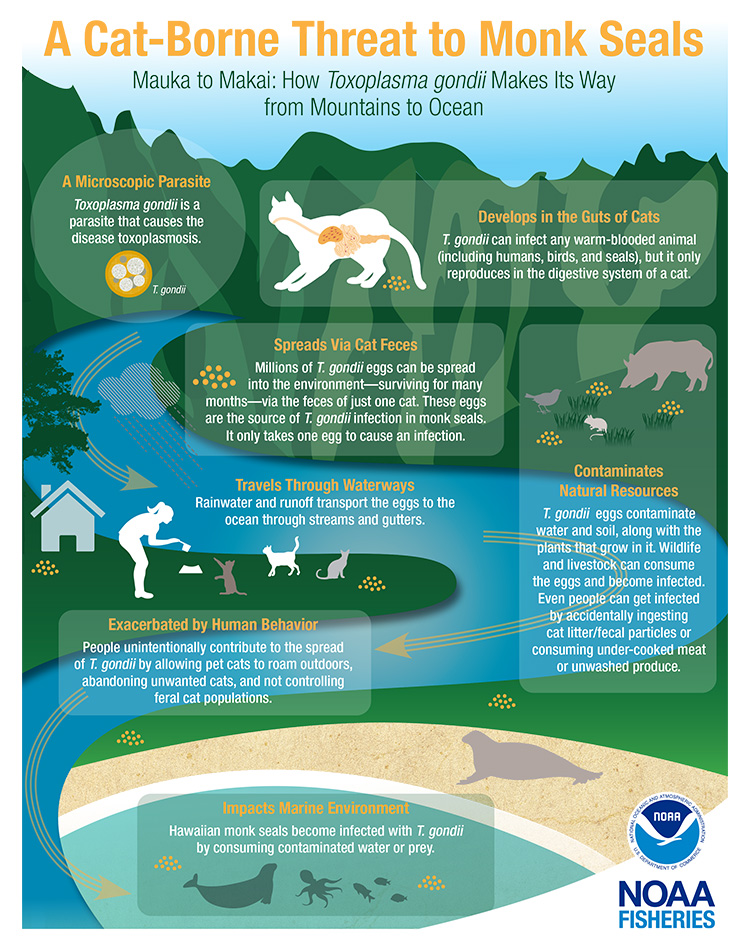

Toxoplasmosis, colloquially known as “toxo,” is a disease caused by a microscopic parasite, T. gondii. Its complex life cycle often leads to confusion about how animals get infected. Cats play a unique, essential role—the parasite can only sexually reproduce in the digestive system of a cat. And unlike all other groups of animals that can get infected with this parasite, “toxo” is shed into the environment exclusively in the fecal matter of cats. Infected cats rarely show any signs of infection. They are indistinguishable from uninfected cats, even during the period of time when they are actively shedding millions of infectious eggs in their feces.

Long after the cat feces decomposes, the eggs remain in the environment and are very resistant to degradation. They are capable of surviving in the soil or in water (fresh or salt), and withstanding a wide range of temperatures for months to about 2 years. When it rains, the eggs wash into the ocean, exposing animals like monk seals that ingest the parasite through contaminated water and infected prey.

Once it gets into a monk seal, the parasite is almost always lethal. T. gondii has also killed other wildlife in Hawaiʻi, including ‘alala (Hawaiian crow), nēnē (Hawaiian goose), and spinner dolphins.

The first documented monk seal death due to toxoplasmosis occurred in 2001. The disease has now killed at least 12 monk seals, making it a leading threat to the main Hawaiian Islands population. Pōhaku is only the third monk seal with toxoplasmosis to be rescued alive; the other two passed away within 48 hours. There are only about 300 seals in all of the main Hawaiian Islands, so 12 deaths from toxoplasmosis is substantial relative to the overall population. And more seals disappear and die without being discovered than are found dead and examined, so the actual number of deaths caused by toxoplasmosis is likely much higher. Furthermore, it appears that the disease affects more females than males. Every lost female means that her future pups, and their future pups, are lost to the world.

The main Hawaiian Islands provide habitat essential for Hawaiian monk seal recovery, with a record number of pups born in 2019. However, these young seals have a less certain future if toxoplasmosis is not addressed soon. If our community is able to overcome this threat, then our hope for the future of our native Hawaiian monk seal burns brighter.

Monitoring and Planning for the Future

NOAA and our partners will continue to do all we can to address this threat. Given the small size of the monk seal population, every individual is important. This is particularly true of breeding-age females, which contribute to population growth. We have been hands-off when it comes to adult females—unless they are in a life-threatening situation—to avoid any potential chance, however small, of impacting a potential pregnancy. However, due to the severity of the toxoplasmosis threat and its disproportionate impact on females, we may be forced to pursue more invasive health monitoring for breeding females in the future. This could include capturing individuals on multiple occasions to monitor for disease exposure or actual illness.The seals would have to bear the cost of this enhanced monitoring, but it may be the only way we can save lives until the source of this issue is more holistically addressed.

NOAA is also working with partners throughout the state to develop a strategic plan. It will outline a suite of actions that we believe will reduce the impact of toxo on monk seals and other native wildlife in Hawaiʻi. We hope the plan will serve as a useful tool for agencies and organizations throughout the state looking to take action to address this issue. We anticipate the plan will be completed in late summer/early fall of this year.

What Can You Do to Help

There are some simple actions that everyone can take that will make a significant difference in reducing monk seal exposure to T. gondii. The single biggest thing you can do is help keep cats in Hawaiʻi indoors. Keep your pet cats inside and dispose of litter in the trash—not by flushing it down the toilet. Indoor cats not only live much longer, healthier lives than outdoor cats, but they are also far less likely to contract the parasite. And even if they somehow do, they will not be defecating T. gondii into the environment. Transitioning an outdoor cat to an indoor lifestyle can be challenging, but it will save lives—seals, wildlife, and the cats themselves.

Letting cats roam outdoors is not a requirement for their well being.Providing cats with a varied, enriching indoor environment is key to their welfare and strengthens the bond between beloved pets and their owners. “Catios” or cat window boxes are also a great way to give your cat some sunshine and fresh air while still keeping it contained. It might sound funny, but many cats can be trained to walk on leashes, especially if you start when they are young. There are also a variety of food puzzles and other interactive games and structures that keep cats entertained and fulfill their instinctual needs within the safety of your home.

Not all cats in Hawaiʻi have homes, however. A comprehensive solution to the threat of toxoplasmosis must also address unowned cats that live outdoors. The community must come together to find solutions that are scientifically supported and provide the best outcomes for both cats and native Hawaiian wildlife.

Another simple, but potentially life-saving action, is to call our Marine Mammal Stranding Hotline at (888) 256-9840 if you see a seal exhibiting a behavior called “logging.” Logging means a seal is floating on the surface of the ocean (like a log or piece of driftwood), acting lethargic, and not actively swimming. Logging is not necessarily a cause for alarm, and some seals may exhibit this behavior for short periods of time even when they appear healthy. However, it is often an indicator of injury or other health problems like toxo. Calling the hotline to report logging allows us to evaluate the animal’s condition as soon as possible. In fact, Pōhaku might not be alive today if someone hadn’t promptly reported her logging. Better safe than toxo!

What Does RO28’s Case Mean for Other Seals: A Sign of Hope, But Not a Solution

While we are seeing success with Pōhaku’s treatments so far, there is still a lot of uncertainty ahead. And even if successful, the life-saving efforts she has undergone in treatment are intensive, laborious, risky to the animal and the caregivers. They are very stressful for wild animals that don’t know we are trying to help them. We also know that Pōhaku is the rare exception—most seals, like Sole, are found dead without warning. Treatment of individual monk seals is the last resort, and it is not a viable solution to the threat of toxoplasmosis.

Even though treatment is not the primary solution, the good news is future infections are entirely preventable. The power of prevention lies in the hands of the community. Eradicating this threat requires that Hawaiʻi move towards indoor-only living for all cats in the state. Such a movement would put Hawaiʻi on the world stage in addressing this important disease. Indoor lifestyles are better for cats, better for wildlife, and better for people too. The sooner this happens, the more wildlife will be saved.

Learn more about the Toxoplasma parasite from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website