Celebrating Reliable Shark Tagging Citizen Scientists

Meet some of the people who exemplify what it means to be a reliable tagger for NOAA’s Cooperative Shark Tagging Program.

The Cooperative Shark Tagging Program began in 1962 with fewer than 100 volunteer fishermen. Since then, thousands of fishermen have contributed data through catch and release fishing, and some of those original volunteers are still with the program today. Their reliability as taggers plays an instrumental role in the continued success of the program. Anyone can volunteer to be a tagger. NOAA requires compliance with all federal, state, and local regulations, safe handling practices for both the tagger and the shark, good record keeping, and an overall positive representation of the program. This article highlights four taggers who demonstrate what it means to be a reliable tagger. They share their perspectives on participating in citizen science.

Rick Stringer: Recreational Fisher, Folly Beach, South Carolina

Sharks tagged: 1,200

After reading about Jack Casey’s citizen science initiative in 1973, Rick Stringer wrote a letter to Casey requesting to join the tagging program. Stringer had always had an interest in sharks. He eventually realized that tagging and releasing them was a way to enjoy the sport of shark fishing without harming the sharks.

The careful records Stringer keeps and his near-perfect rate of returning these records allow for his continued success in the program. For example, he notes the distinguishing characteristics that he uses to accurately identify the species he catches.

Stringer finds the tagging program personally interesting. He also believes it is beneficial to science because of the changes he has observed and documented throughout his years of tagging.

“I tagged a blue shark in South Carolina, for example, which I’d never seen there before. I tagged it 4 or 5 miles offshore, and it ended up more than 1,000 miles back in the Atlantic,” said Stringer.

“I’ve spent my life fishing around here inshore,” he continued. “Migration changes, and I’m seeing sharks earlier that I wouldn’t have seen before. Seeing and documenting these changes is one of the many benefits of the tagging program.”

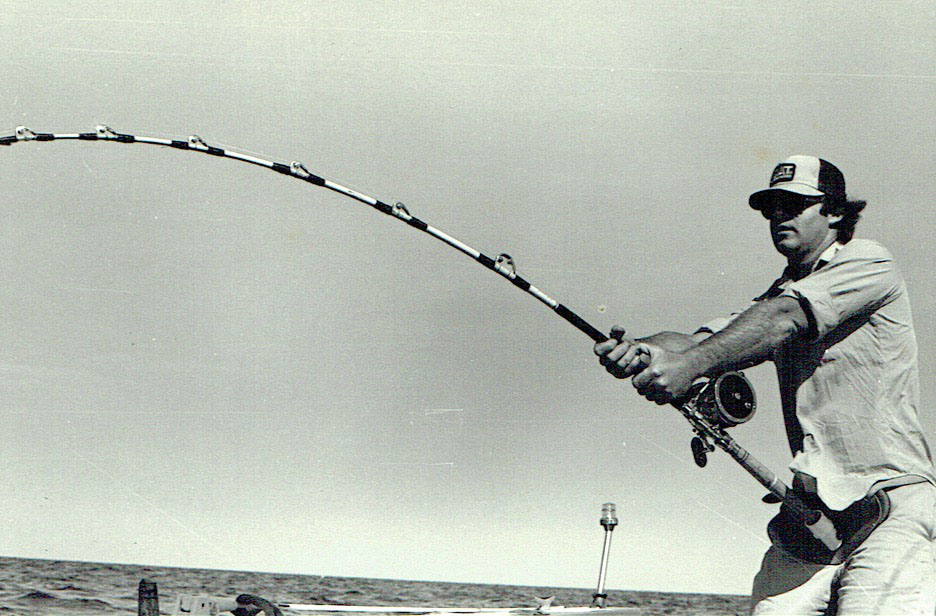

John Henry David: Recreational Fisher, Neptune, Florida

Sharks tagged: 1,400

In 1973, John Henry David joined a Florida shark fishing club. He participated in the tagging program, part of NOAA’s Apex Predators Program, run by Jack Casey at the time, as a club activity. In the 1980s, David became aware of population declines in several species of fish, including sharks. He understood that overfishing of sharks would lead to more species becoming endangered and overall unhealthy ecosystem dynamics in the ocean.

David also knows his tagging work can help researchers better manage shark populations from a conservation standpoint.

“I continued to tag because I really liked catching sharks,” he said. “I was participating in the research, helping shark populations, and helping us understand them better. So, I started tagging, and I just never looked back.”

David’s personal record keeping in spreadsheets keeps information accessible and prevents loss of data. This came in handy when he was able to find information for 19 tags for which data had been lost in the mail.

NOAA also prioritizes the safety of volunteer taggers as well as the fish tagged. David exemplifies this by fishing with his first mate, Logan Ironside. “I don’t fish without him. I need people I can trust who know what they’re doing out there so we don’t get hurt,” said David. By having a dedicated crew, the tagging process is streamlined, minimizing handling and ensuring a quick release that keeps the shark healthy.

Jim Knight: Recreational Land-Based Fisher, Galveston, Texas

Sharks tagged: 445

In 2006, Jim Knight started tagging sharks with a friend who had received tags from NOAA. Recapturing a couple of previously tagged sharks piqued Knight’s interest, and he decided he wanted to start regularly tagging the sharks he caught. Knight appreciates working with NOAA’s Cooperative Shark Tagging Program, from the ease of sending in tag information and the quality of the tags, to the program reporting back to the tagger with data from recaptures

Knight fishes in Texas when the sharks first start showing up in the spring. He knows the sharks leave in the fall and tags the fish he catches to help scientists learn more about where they go. When he’s not fishing in Texas, Knight heads to Florida for the winter and tags the species that winter there too.

Fishing from shore, Knight faces the unique challenges of catching sharks in the eyes of the public. He strives to avoid negative attention, leaving the shark in the water and working quickly to tag and release the shark. When approached, he tells people that although he’s not a scientist and tagging isn’t his job, he tags the fish he catches to help better understand shark movements.

“I explain to anybody who's concerned that there’s more to it than just fishing for sharks,” he said.

While he enjoys shark fishing, he also enjoys tagging and releasing the sharks he catches to learn about their migrations and to help NOAA better manage them.

Charlie Locke: Commercial Fisher, Wanchese, North Carolina

Sharks tagged: 200

In 2010, Charlie Locke began to recapture several previously tagged sandbar sharks. Intrigued by the idea of seeing where sandbars and other species go and when, Locke requested tags to begin tagging himself.

“I was fascinated with marine biology and Jacques Cousteau when I was growing up. I was never a marine biologist, but I love fishing, so starting to tag was a natural transition,” he said.

Locke fishes commercially for a variety of fish species. In some fisheries, sharks are considered bycatch. When he catches a shark, he takes advantage of this opportunity by tagging it. He understands the significance tagging sharks can have for shark researchers.

“I started to see the value of the information we were collecting, and that’s what inspired me to be part of it,” he said. “I want to be seen as a team player with the shark science community, and I’m doing my part by tagging the sharks that I’m already catching.”

Now, tagging is second nature for Locke, just as much a part of his work as catching fish to sell. Although he doesn’t make money from tagging, Locke feels the reward is in contributing to shark research.

“There’s no financial reward for doing it, but for me, it’s about being part of the science community,” he said, “and I have a great opportunity to put out tags that a lot of other people don’t have.”