Chief Scientist’s Weather Report: clearing skies, sunshine …. But we’re not really aware of that because we’re in a dark room with all eyes riveted on the video feeds from ROPOS.

Once we left Newport, the seas turned rough, and some of our crew of intrepid scientists had to weather the dreaded “mal de mer” (seasickness) until we got our “sea legs.” After a 20-hour steam at 11 knots, we finally arrived at our station above an unnamed submarine canyon at the edge of the continental shelf between Powell and Munson canyons.

With the sea state within launch limits (that is, wind speeds less than 25 knots and wave height less than 7 feet), we were anxious for our first dive to get underway. The ROPOS’s and ship’s crews were also ready, and in consultation with Matt Poti from NOAA’s National Ocean Service, our expert map maker and deep-sea coral habitat modeler, we knew exactly where we wanted to go. See We Got Caught Mapping and More Than Just a Pretty Map for an explanation of seafloor mapping and habitat suitability modeling.

The area in the unnamed canyon that we picked was in the central channel between 960 to 1232 meters (roughly 3,150 to 4,050 feet) deep. On the bathymetric maps it appeared to have a unique shape: a depression in the channel with steep-sided walls almost all the way around it. In other words: perfect for deep-sea corals. Most deep-sea corals live on hard bottoms or substrates and often on topographic highs such as the steep, rocky walls of submarine canyons. Our dive plan was to follow the walls all the way around the depression.

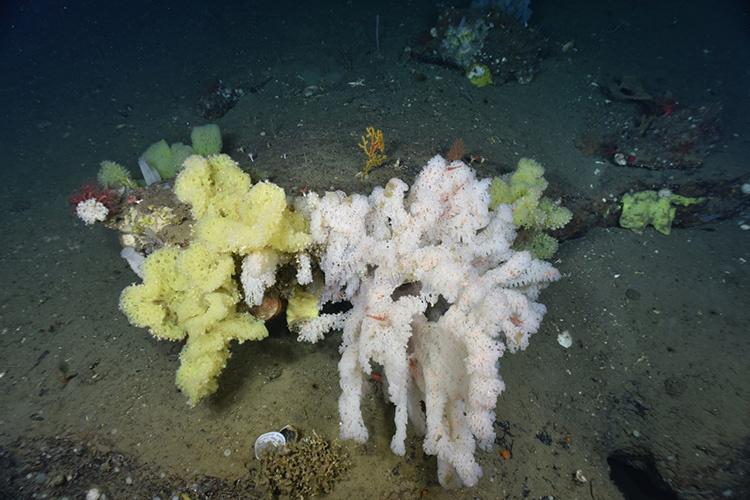

And it was indeed perfect for deep-sea corals, and also unique! Most of the animals we saw were around or attached to rocky terraces, steps, exposed bedrock, and overhangs that often extended out of the walls or slopes; the slopes themselves were often covered with fine muddy sediment. Some of the animals we saw and/or collected throughout the dive included black corals, true soft corals, bamboo corals and other gorgonian sea fans, and stony corals. Large white and yellow glass sponges, flame clams, and Brisingid sea stars were also observed. Of note is that we saw 14 Graneledone octopuses, more than we’ve ever seen before!

Several of the animals were more abundant here than in other canyons we have explored. For example, the abundance of black corals in particular was exciting because they are truly deep-sea, and until a few years ago there were hardly any records of black corals in the northeast.

Conversely, some corals we expected to be relatively abundant were hardly found here at all. This reinforces our hypotheses that each submarine canyon is unique regarding the types and abundances of the deep-sea corals found there, and habitats within a canyon are variable and can host different sets of animals.

With the ROPOS back on deck after a dive, there’s still a lot of work do before we can relax. There is of course ROPOS maintenance to be done, planning for tomorrow morning’s dive, processing data (and most importantly: saving data!), and processing specimens for identification, aging studies, genetics, etc. It’s hard work and once all that is done, it really is time to relax and celebrate a little by perhaps enjoying some ice cream from the ship’s ice cream freezer, because with all the great food on this trip, what’s another 200 calories? (At least that is what we tell ourselves.)

Dave Packer, NOAA Fisheries Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Aboard the NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow HB 19-03