Biomass estimates tell us how much krill are around Antarctica’s South Shetland Islands each year, but they don’t tell us anything about what the environment is like. Krill like to live in places with comfortable temperatures and lots of good food to eat—mainly phytoplankton. But how can we discover what amounts to a “five-star resort” for krill?

Krill can’t leave online reviews of their habitat each year, but if they could, I imagine they would read something like this:

- Five stars! I was worried because the winter sea ice retreated early this year, but I was pleasantly surprised by the deep range of cold, nutrient-rich water to explore. So many juicy diatoms to eat! Would recommend!

- One star. Meh. I had high hopes because the winter sea ice stuck around into spring, and the water was warm, not too salty, and there was tons of sunshine and phytoplankton. But even though there was plenty of food, the portions were so small that I had trouble eating them, and no matter how much I ate, I never felt full. Did not meet expectations.

Since krill can’t tell us what makes a habitat favorable for them, we use sensors on the gliders. These sensors measure water temperature, salinity, oxygen concentration, and chlorophyll concentration, to help us understand what environmental conditions krill may prefer.

Five-Star Habitat

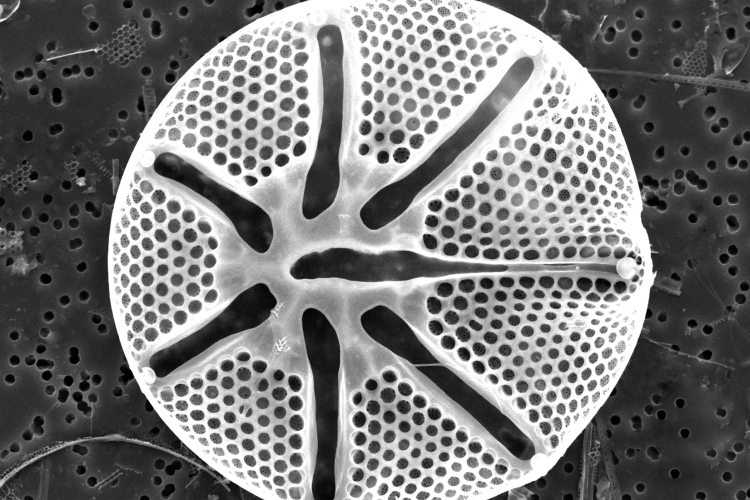

Sea ice covering the ocean surface prevents the wind from mixing the upper ocean, where krill spend most of their time. When the ice begins to recede early in spring as the days get longer and there’s more sunlight, the wind stirs up the upper layer of the ocean, bringing cold water and nutrients to the surface. More nutrients are good for phytoplankton that need them to photosynthesize (the process of converting carbon dioxide to sugar for nutrition). However, lots of mixing can suspend lots of particles in the water, which can reduce the amount of sunlight that can penetrate the upper layer of the ocean. Since sunlight is also necessary for photosynthesis, it may seem counter-intuitive that cold, salty, murky water would lead to phytoplankton options worthy of a five-star review. Fortunately for krill, many species of their favorite phytoplankton—diatoms—thrive in just these conditions.

Our gliders don’t tell us what species of phytoplankton are in the water. Instead, they measure chlorophyll concentration. Chlorophyll is the pigment in plants and algae that makes them appear green, and it’s the pigment that captures the sun’s energy and allows them to photosynthesize. When gliders measure high chlorophyll and oxygen concentrations near the ocean surface, we can infer that there’s lots of phytoplankton in the water producing oxygen through photosynthesis.

Here’s the tricky part. A habitat that’s favorable for krill—one that contains lots of diatoms—may actually have low chlorophyll concentration. In the phytoplankton world, diatoms are giants. That’s why krill prefer them—their size and nutritional quality make them a krill “superfood.” But because diatoms are so big compared to other phytoplankton species, chlorophyll measurements may be a bit deceptive.

Picture two ball pits that are the same size. One is full of ping pong balls, and the other is full of basketballs. Each ping pong ball and each basketball has a little green circle painted on it, and the green circle is the same size for all the balls. The ball pit with the ping pong balls will have many more green circles in it because ping pong balls are so much smaller than basketballs, so more of them can fit in our ball pit. If diatoms are the basketballs of phytoplankton, then it may appear there’s less chlorophyll in the water when diatoms are abundant.

One-Star Habitat

When sea ice melts later in spring, as the water warms up with the longer days and more sunlight, the fresh water from the melting ice forms a layer on top of the saltier water below that is full of nutrients. Because this layer of fresher water is less dense than the layer of saltier water beneath it, the two layers don’t mix very much, trapping those nutrients near the surface. The layer of fresher water gets warm in the sunshine, creating a perfect environment for phytoplankton to bloom like crazy. Gliders detect these areas as warm and not very salty, with high chlorophyll and oxygen concentrations.

This habitat sounds perfect for krill, right? So, why the one-star review? Just like in the five-star review, it’s all about the dining options. While diatoms are a krill superfood, the phytoplankton that grow in these one-star conditions are small and not very nutritious (they are the ping pong balls of phytoplankton). They’re so small that krill have trouble eating them. Even when they do eat them, they don’t gain much energy from them. That’s why chlorophyll and oxygen concentrations are high in these one-star habitats: If krill don’t eat the phytoplankton there, lots of phytoplankton remain in the water, photosynthesizing and generating oxygen.

These five-star and one-star habitats are examples of what the marine ecosystem in our study area may look like in any given year. But because ocean conditions are unpredictable, there’s room for two-, three-, and four-star reviews. Storms, ocean circulation patterns, or weather patterns—El Niño and La Niña, for example—may create mash-ups of our five-star and one-star habitats. Each year, we consider our krill biomass estimates along with ocean conditions measured by gliders. We want to see if we can tease out whether krill habitat is more like a fancy resort, a middle-of-the-road hotel, or a budget motel. Krill are harsh critics.