Humpback Whale

Megaptera novaeangliae

Protected Status

Western North Pacific DPS

Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa DPS

Central America/Southern Mexico - California-Oregon-Washington stock

Mainland Mexico - California-Oregon-Washington stock

Quick Facts

Humpback whale breaching. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Humpback whale breaching. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Humpback whale breaching. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Humpback whale breaching. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Humpback whale breaching. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Humpback whale breaching. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Before a final moratorium on commercial whaling in 1985, all populations of humpback whales were greatly reduced, most by more than 95 percent. The species is increasing in abundance throughout much of its range but faces threats from entanglement in fishing gear, vessel strikes, vessel-based harassment, and underwater noise.

Humpback whales live in all oceans around the world. They travel great distances every year and have one of the longest migrations of any mammal on the planet. Some populations swim 5,000 miles from tropical breeding grounds to colder, more productive feeding grounds. Humpback whales feed on shrimp-like crustaceans (krill) and small fish, straining huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates, which act like a sieve.

The humpback whale gets its common name from the distinctive hump on its back. Its long pectoral fins inspired its scientific name, Megaptera, which means “big-winged” and novaeangliae, which means “New England,” in reference to the location where European whalers first encountered them. Humpback whales are a favorite of whale watchers―they are often active, jumping out of the water and slapping the surface with their pectoral fins or tails.

NOAA Fisheries is dedicated to the conservation of humpback whales. Our scientists use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and disentangle humpback whales. We also work with our partners to ensure that regulations and management plans are in place to reduce entanglement in fishing gear, create safer shipping lanes, and protect habitats.

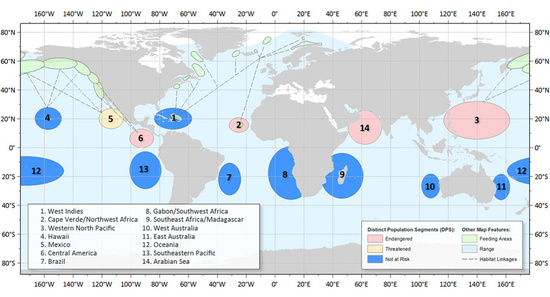

Population Status

Commercial whaling severely reduced humpback whale numbers from historical levels. The United States listed all humpback whales as endangered under the Endangered Species Conservation Act in 1970 and then under the Endangered Species Act in 1973. NOAA Fisheries worked worldwide to identify and apply protections for humpback whales. The International Whaling Commission’s final whaling moratorium on commercial harvest, in effect since 1985, played a major role in the recovery of humpback whales. Currently, four out of the 14 distinct population segments are still protected as endangered, and one is listed as threatened (81 FR 62259, September 2016). Three humpback whale stocks in U.S. waters are designated as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (see annual stock assessment report).

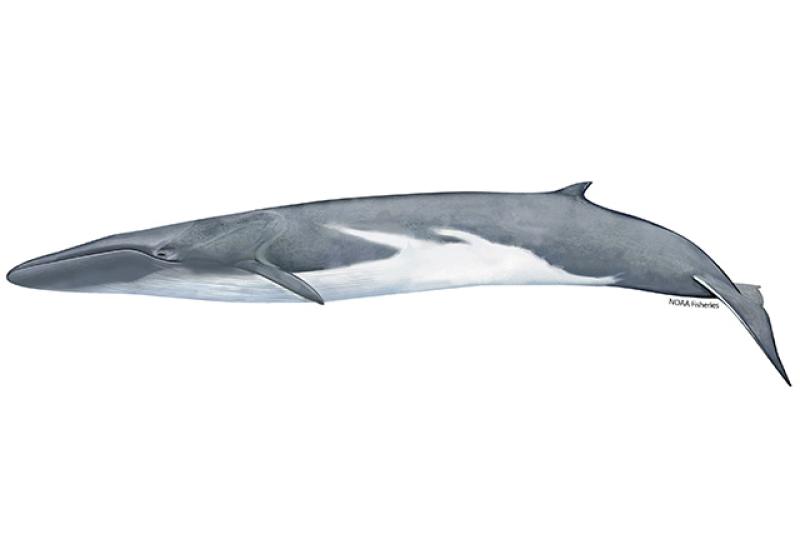

Appearance

Humpback whales’ bodies are primarily black, but individuals have different amounts of white on their pectoral fins, bellies, and the undersides of their flukes (tails). Southern Hemisphere humpback whales tend to have more white markings, particularly on their flanks and bellies than do Northern Hemisphere humpback whales.

Humpback whale flukes can be up to 18 feet wide—they are serrated along the trailing edge, and pointed at the tips. Tail fluke pigmentation patterns, in combination with varying shapes and sizes of whales’ flukes and/or prominent scars, are unique to each animal. They are distinctive enough to be used as “fingerprints” to identify individuals.

When photographed, scientists can often identify individual whales—a process called photo-identification - and catalog occurrences of individual whales and use this information to track them over time.

Behavior and Diet

Humpback whales are a favorite of whale-watchers, as they can be found close to shore and often display activities near the surface, such as breaching (jumping out of the water) or slapping the surface with their pectoral fins and tails.

During the warmer months (and occasionally into cooler months), humpback whales spend most of their time feeding and building up fat stores (blubber) to sustain them throughout the winter. Humpback whales filter-feed on small crustaceans (mostly krill) and small fish. They use several techniques to help them herd, corral, and disorient prey and that can include using bubbles, sounds, the seafloor, and even their pectoral fins. One specific feeding method, called "group coordinated bubble net feeding," involves using curtains of air bubbles to condense prey. Once the fish are corralled, they are pushed toward the surface and engulfed as the whales lunge upward through the circular bubble net. Different groups of humpback whales use other bubble structures in similar ways, though there appears to be some regional specialization in bubble-feeding behaviors among populations.

Where They Live

Humpback whales live throughout the world's major oceans. They can travel great distances during their seasonal migration with some animals migrating 5,000 miles between high-latitude summer feeding grounds and winter mating and calving areas in tropical waters. In the North Pacific, some humpback whales migrate from Alaska to Hawaiߵi—they can complete the 3,000 mile trip in as few as 28 days. While calving, they prefer shallow, warm waters commonly near offshore reef systems or shores. Humpback whale feeding grounds are generally in cold, productive waters.

At least four humpback whale populations occur in the North Pacific:

- Mexico population

- Breeds along the Pacific coast of Mexico and the Revillagigedo Islands

- Transits the Baja California Peninsula

- Feeds across a broad range from California to the Aleutian Islands, Alaska

- Central America population

- Breeds along the Pacific coast of Central America, including off Costa Rica, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua

- Feeds off the West Coast of the United States and southern British Columbia

- Hawaiߵi population

- Breeds in the main Hawaiian Islands

- Feeds in most of the known feeding grounds in the North Pacific, including the Aleutian Islands/ Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, Southeast Alaska, and northern British Columbia

- Western North Pacific population

- Breeds in the areas of Okinawa, Japan, and the Philippines

- Feeds in the northern Pacific, primarily in the West Bering Sea and off the Russian coast and the Aleutian Islands

- Also evidence for the existence of a lesser-known breeding area in the western North Pacific

In the North Atlantic, two populations of humpback whales feed during spring, summer, and fall throughout a range that extends across the Atlantic Ocean from the Gulf of Maine to Norway. These two populations migrate south during the winter to calve and mate in the West Indies and Cape Verde (off the coast of Africa), and possibly in other areas.

Seven populations of humpback whales are found in the Southern Hemisphere, all of which feed in Antarctic or sub-Antarctic waters.

World map providing approximate representation of the humpback whale's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the humpback whale's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Humpback whales reach sexual maturity between the ages of 4 and 10 years. Females produce a single calf every 2 to 3 years on average, although annual calving has been documented in some individuals. Calves are born after an 11-month gestation and measure about 13 to 16 feet in length. Calves stay near their mothers for up to 1 year before weaning. Mothers are protective of their calves, swimming closely and often touching them with their flippers. While calves are not believed to maintain long-term associations with their mothers, they are more likely to be found in the same feeding and breeding areas as their mothers.

Threats

Vessel Strikes

Inadvertent vessel strikes can injure or kill humpback whales. Humpback whales are vulnerable to vessel strikes throughout their range, but the risk is much higher in coastal areas with heavier ship traffic.

Climate Change

The impacts of climate change on whales are unknown, but it is considered one of the largest threats facing high latitude regions where many humpback whales forage. Most notably, the timing and distribution of sea ice coverage is changing dramatically with altered oceanographic conditions. Any resulting changes in prey distribution could lead to changes in foraging behavior, nutritional stress, and diminished reproduction for humpback whales. Additionally, changing water temperature and currents could impact the timing of environmental cues important for navigation and migration.

Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Humpback whales can become entangled by many different gear types, including moorings, traps, pots, or gillnets. Once entangled, if they are able to move the gear, the whale may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances, ultimately resulting in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury, which may lead to reduced reproductive success or even death. There is evidence to suggest that most humpback whales experience entanglement over the course of their lives but are often able to shed the gear on their own. However, the portion of whales that become entangled and do not survive is unknown.

Vessel-Based Harassment

Whale watching vessels, recreational boats, and other vessels may cause stress and behavioral changes in humpback whales. Because humpback whales are often found close to shore and generally surface in an active state, they tend to be popular whale watching attractions. There are several areas within the United States where humpback whales are the central attraction for the whale watching industry, including the Gulf of Maine (particularly within the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary), California, Alaska (particularly southeast Alaska), and the Hawaiian Islands.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Balaenopteridae | Genus | Megaptera | Species | novaeangliae |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024

What We Do

Conservation & Management

All humpback whales are protected under the MMPA, and five populations are protected under the ESA. Our work includes:

- Reducing the risk of entanglement in fishing gear

- Developing methods to reduce vessel strikes

- Responding to dead, injured, or entangled humpback whales

- Educating the whale watching/tourism industry and vessel operators on responsible viewing of humpback whales

- Partnering to implement the Whale SENSE program, a whale watching stewardship, education, and recognition program to increase wildlife viewing standards

Science

We conduct various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of humpback whales. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this ecologically, economically, and socially important species that is endangered in certain areas. Our work includes:

- Monitoring humpback whale abundance and mortality in U.S. waters

- Studying humpback whale population structure

- Collaborating with international scientists to track the movements and behavior of humpback whales as they migrate across international boundaries

How You Can Help

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all larger whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards by sea or land.

In Hawaiߵi and Alaska, it is illegal to approach a humpback whale within 100 yards, by land or sea. It is also illegal to approach humpback whales in Hawaiߵi within 1,000 feet (333 yards) by air.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Reduce Speed and Be on the Lookout

Vessel collisions are a major cause of injury and death for whales. Here are some tips to avoid collisions:

Be Whale Aware. Know where whales occur (habitat).

Watch your speed in areas of known marine mammal occurrence. Keep speeds to 10 knots or less to reduce potential for injury.

Keep a sharp lookout. Look for blows, dorsal fins, tail flukes, etc. However, be aware that most captains report never seeing a whale prior to colliding with it.

Protect your boat, protect your passengers. Boats can be heavily damaged and even "totalled" after colliding with a large whale. Collisions can also injure passengers.

Keep your distance. Stay at least 100 yards away.

Stop immediately if within 100 yards. Slowly distance your vessel from the whale.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

Trained responders trailing the humpback whale off Pacific Grove, California on April 5 as they make the final cut to free the whale from its entangling gear. Collected in partnership with The Marine Mammal Center, Marine Life Studies and Cascadia Research Collective under NOAA Permit #24359.

Trained responders trailing the humpback whale off Pacific Grove, California on April 5 as they make the final cut to free the whale from its entangling gear. Collected in partnership with The Marine Mammal Center, Marine Life Studies and Cascadia Research Collective under NOAA Permit #24359.

Common dolphins. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Michelle Klein

Common dolphins. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Michelle Klein

Celebrating 15 Years of Surveying Protected Species in the Northwest Atlantic

A school of northern right whale dolphins observed off Oregon on the recent Southwest Fisheries Science Center marine mammal survey. Image collected under NOAA Fisheries research permit #22306. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Cory Hom-Weaver.

A school of northern right whale dolphins observed off Oregon on the recent Southwest Fisheries Science Center marine mammal survey. Image collected under NOAA Fisheries research permit #22306. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Cory Hom-Weaver.

Four-Month Survey Tracking West Coast Marine Mammals Finds Some Shifting North

Alaska Stranding Network members examined a young, male humpback whale (2024097) on July 8, 2024 near Elfin Cove. Members included a veterinarian with Alaska Veterinary Pathology Services and a biologist with Glacier Bay National Park. Credit: Alaska Veterinary Pathology Services.

Alaska Stranding Network members examined a young, male humpback whale (2024097) on July 8, 2024 near Elfin Cove. Members included a veterinarian with Alaska Veterinary Pathology Services and a biologist with Glacier Bay National Park. Credit: Alaska Veterinary Pathology Services.

Management Overview

The humpback whale Central America distinct population segment (DPS), Western North Pacific DPS, Arabian Sea DPS, and Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa DPS are listed as endangered and the Mexico DPS is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The humpback whale is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

The Western North Pacific stock, Central America/Southern Mexico - California-Oregon-Washington stock, and the Mainland Mexico - California-Oregon-Washington stock are depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the humpback whale is listed under:

- Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

NOAA Fisheries has made significant progress toward the protection of humpback whales worldwide. We have taken many steps to reduce injury and mortality caused by fishing gear, reduce the threat of vessel collisions, minimize the effects of vessel disturbance and noise, and protect habitats that are essential to the survival and recovery of this species.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Actions

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries is required to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. NOAA Fisheries originally developed a recovery plan in 1991 to identify actions that would advance the recovery of the global species and protect its habitats. The ultimate goal of the 1991 Humpback Whale Recovery Plan is to help humpback whales thrive, allowing the species to be reclassified from “endangered” to “threatened,” and ultimately removed from the ESA's list of threatened and endangered species.

The major actions recommended in the existing species-wide recovery plan are:

- Reduce or eliminate injury and mortality caused by fisheries, fishing gear, and vessel collisions

- Minimize effects of vessel disturbance

- Continue the international moratorium on commercial whaling

- Collect as much data as possible from dead whales through our Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Program

Following the 2016 change in the listing status of humpback whales, NOAA Fisheries determined in 2019 that recovery plans would not promote the conservation of the endangered Arabian Sea and the Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa DPSs. We are currently developing an updated, DPS-specific recovery plan for the ESA-listed Central America, Mexico, and Western North Pacific DPSs. In the interim, the recovery strategy for these DPSs will be guided by the existing species-wide plan and a new DPS-specific recovery outline.

Read the recovery plan for the humpback whale

Implementation

Together with our partners, we undertake numerous activities to support the directives of the humpback whale recovery plan, protect humpbacks, and reduce adverse impacts from human activities.

Efforts to implement recovery for humpback whales include:

- Creating marine protected areas for humpback whales

- Minimizing vessel disturbance

- Reducing entanglement in fishing gear

- Reducing vessel strikes

- Understanding and addressing the effects of ocean noise

- Collaborating with the Commission on Environmental Cooperation to develop the North America Humpback Whale Conservation Action Plan for the United States, Canada, and Mexico

Monitoring Plan

NOAA Fisheries collaborated with state and federal agencies to create a monitoring plan for the nine distinct population segments of humpback whales that have recovered and are no longer protected under the ESA. Recently, NOAA Fisheries convened a post-delisting monitoring plan group (PDMP working group) to assemble, review, and discuss any updated data on the nine distinct population segments of humpback whales that no longer meet the definition of a threatened or endangered species and are no longer protected under the ESA. An interim report for the post delisting monitoring plan was published in 2022.

Critical Habitat

Although the original listing of this species predated the requirement for critical habitat designations, the 2016 revision to the humpback whale listing under the ESA triggered the requirement for NOAA Fisheries to designate critical habitat to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. A proposed rule to designate critical habitat for the Central America, Mexico, and Western North Pacific DPSs of humpback whales was published in 2019 and a final rule was published on April 21, 2021.

Learn more about the critical habitat designation

Conservation Efforts

Designating Marine Protected Areas for Humpback Whales

In 1992, the U.S. Congress created the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary to protect humpback whales and their habitat around Hawaii. NOAA Fisheries co-manages the sanctuary with the State of Hawaiߵi, conducts research on humpback whales, and operates a sanctuary education and learning center.

NOAA Fisheries and the Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources have established the world’s first sister sanctuaries to protect humpback whales. The Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, off the coast of Massachusetts, and the Santuario de Mamíferos Marinos de la República Dominicana are two marine protected areas 3,000 miles apart. Around 900 humpbacks spend spring and summer in the rich feeding grounds of Stellwagen Bank before they head south in the late fall to mate and give birth in the warmer waters of the Dominican Republic. The sister sanctuary agreement strengthens coordination and management efforts between the two sanctuaries and improves humpback whale recovery in the North Atlantic.

Minimizing Whale Watching Harassment

NOAA Fisheries supports responsible viewing of marine mammals in the wild and has adopted a guideline to observe all large whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards by sea or land in all areas. In addition, federal approach regulations for humpback whales in Alaska and Hawaii require, with limited exceptions, that you:

- Not approach within 100 yards of a humpback whale

- Not place your vessel in the path of oncoming humpback whales, causing them to surface within 100 yards of your vessel

- Not disrupt the normal behavior or prior activity of a humpback whale

- Operate your vessel at a slow, safe speed when near humpbacks

In Hawaiߵi, regulations also prohibit operating an aircraft within 1,000 feet (333 yards) of a humpback whale.

WhaleSENSE is a voluntary education and recognition program developed by NOAA Fisheries and the Whale and Dolphin Conservation in collaboration with the whale watching industry to recognize whale watching companies committed to responsible practices in the U.S. Atlantic and Alaska.

Companies participating in the WhaleSENSE program agree to:

- Stick to the regional whale watching guidelines

- Educate naturalists, captains, and passengers to have “SENSE” while watching whales

- Notify and report whales in distress

- Set an example for other boaters

- Encourage ocean stewardship

Both Alaska and Hawaiߵi have specific guidance and requirements for minimizing whale watching impacts from tourism on humpback whales and other marine animals.

Reducing and Responding to Entanglement

Entanglement in fishing gear is a leading cause of serious injury and death for many whale species, including humpback whales.

In the Atlantic, we implemented the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan to reduce the incidental mortality and serious injury of right whales, humpback whales, and fin whales in gillnets and trap/pot fisheries along the East Coast.

In the Pacific, we are working with state fishery management working groups to reduce the risks of entanglements in Dungeness crab pot fisheries, including the California Risk Assessment and Mitigation Program (RAMP) used to detect and respond to increased entanglement risk. NOAA Fisheries Science Centers are engaged in significant efforts to improve the scientific understanding of the drivers that may be influencing the risks of entanglements for whales along the U.S. West Coast. We also implemented the Pacific Offshore Cetacean Take Reduction Plan to reduce mortalities and serious injuries of several marine mammal stocks, including humpback whales, incidentally injured in the California thresher shark/swordfish drift gillnet fishery.

In Alaska, we have a network of trained entanglement responders around the state. When an entangled whale is reported, responders can be authorized to evaluate the entanglement and, in cases where the entanglement is life threatening to the animal and a response can be carried out safely, a team may attempt to cut the whale free from gear.

Learn more about large whale entanglement and how NOAA Fisheries is addressing this threat

Learn more about bycatch and fisheries interactions

Reducing Vessel Strikes

Collisions between whales and large vessels can injure or kill whales, damage the vessels, and injure passengers, but they often go unnoticed and unreported. The most effective way to reduce collision risk is to give whales a wide berth or avoid areas of high whale concentrations altogether. If this is not possible, the second best option is for vessels to slow down and keep a lookout.

In the Atlantic, we have taken both regulatory and non-regulatory steps to reduce the threat of vessel collisions to North Atlantic right whales. These actions, may also reduce the threat of vessel collisions to humpback whales, which occur in the same waters. The steps include:

- Requiring vessels to slow down in specific areas during specific times (Seasonal Management Areas)

- Advocating for voluntary speed reductions in Dynamic Management Areas

- Recommending alternative shipping routes and areas to avoid

- Modifying international shipping lanes

- Developing mandatory vessel reporting systems

- Increasing outreach and education

- Improving our stranding response

Learn more about vessel strikes and marine animals

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

There is an ongoing Humpback Whale Unusual Mortality Event, and the species has experienced unusual mortality events in the past. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Get information on active and past UMEs

Get an overview of marine mammal UMEs

Addressing Ocean Noise

Underwater noise can pose a threat to whales, interrupting their normal behavior and potentially causing temporary or permanent reductions in hearing. NOAA Fisheries is investigating all aspects of acoustic communication and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on whale behavior and hearing. In 2018, we issued technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic (human-caused) sound on marine mammal hearing.

Regulatory History

Commercial whaling severely reduced humpback whale numbers from historical levels, and the United States listed all humpback whales as endangered in 1970. NOAA Fisheries worked nationally and internationally to identify and apply protections for humpback whales. The International Whaling Commission’s whaling moratorium, in effect since 1985, played a major role in the recovery of humpback whales.

NOAA Fisheries developed a recovery plan in 1991 to identify actions that would protect the species in important breeding and feeding areas. In addition, we have taken steps to reduce threats to the species, such as establishing regulations to:

- Restrict vessel and aircraft distance from humpbacks to reduce disturbance

- Limit vessel speed in certain areas to reduce the likelihood of deaths and serious injuries from vessel strikes

In 2015, we completed a global status review of humpback whales, and in 2016, we revised the ESA listing for the humpback whale to identify 14 distinct population segments. We determined that nine populations have recovered enough that they do not warrant listing, while four populations are still protected as endangered (Central America, Western North Pacific, Arabian Sea, and Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa). The Mexico population is listed as threatened.

All humpback whales are protected under the MMPA and three stocks are listed as depleted (i.e., they have fallen below their optimum sustainable population levels). Under the MMPA, the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan and Pacific Offshore Cetacean Take Reduction Plan address the threat of fishery entanglements.

Key Actions and Documents

Incidental Take Authorization: Alaska Railroad Corporation's Seward Freight Dock construction project in Seward, Alaska

Incidental Take Authorization: United States Coast Guard's Base Kodiak Homeporting Facility in Kodiak, Alaska

Incidental Take Authorization: Pacific Air Forces Regional Support Center's construction activities at Eareckson Air Station Fuel Pier Repair in Alcan

Incidental Take Authorization: City of Hoonah’s Cargo Dock Project in Hoonah, Alaska

More Information

- Report a Stranded or Injured Humpback

- Marine Life Viewing Guidelines

- Alaska Marine Mammal Viewing Guidelines and Regulations

- Whale Alert Smartphone App

- ESA Section 7 Consultations

- Marine Mammal Permits and Authorizations

- Buying or Finding Marine Mammal Parts and Products

- Unusual Mortality Events

- Humpback Whale Contacts

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the humpback whale. The results are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this species.

Shipboard Studies

NOAA Fisheries conducts research cruises that investigate the whales’ habitat preferences and feeding ecology, as well as doing photographic and genetic identification. Information from these research projects can be used to inform management actions that protect the humpback whale and reduce their human-related mortalities.

The Years of the North Atlantic Humpback Project in 1992 to 1993 and the follow-up project, More North Atlantic Humpbacks, in 2003 to 2005 were international collaborations to monitor humpback whale populations, investigate human-caused deaths, and conduct various other surveys, including research on humpback songs, across many humpback habitats.

The Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance, and Status of Humpbacks (SPLASH) Project, conducted from 2004 to 2006, brought together many research programs and researchers from across the world, including NOAA Fisheries, to monitor humpbacks.

Through a multi-year project, researchers from NOAA Fisheries, Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, and partner organizations have made advancements in how humpback whales are tagged. The detailed information about individual whales collected from the tags over many years is informing humpback whale conservation biology.

Acoustic Science

Other research is focused on the acoustic environment of cetaceans, including humpback whales. Acoustics is the science of how sound is transmitted. This research involves increasing our understanding of the basic acoustic behavior of whales, dolphins, and fish; mapping the acoustic environment; and developing better methods to locate cetaceans using autonomous gliders and passive acoustic arrays.

Learn more about acoustic science

Aerial Surveys

Scientists use small aircraft to spot large whales (including humpbacks) and record their seasonal distribution. Understanding their migration patterns helps managers establish measures to reduce vessel strikes.

Stock Assessments

Determining the size of humpback whale populations helps resource managers determine the success of conservation measures and regulations. Our scientists collect population information on humpback whales from various sources and present the data in an annual stock assessment report.

Learn more about marine mammal stock assessments

Find humpback whale stock assessment reports

A humpback whale feeding. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Humpback Whales in Alaska

Our research on the population dynamics, diet and foraging behavior, distribution, and movement patterns of humpback whales provides information crucial for understanding and protecting humpback whale populations in Alaska.

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024

Documents

Biological Opinion NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources, Permits and Conservation Division, Eareckson Air Station Long-term Fuel Pier Repairs, Shemya Island, Alaska

This opinion considers the effects of all in-water activities including vessel transit of materials…

Biological Opinion United States Army Corps of Engineers, Dutch Harbor Light Cargo Dock Screeding, Unalaska, AK

This opinion considers the effects of screeding and slope stabilization on listed and proposed…

Biological Opinion National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region, Sustainable Fisheries Division Fishery Management Plan for the Groundfish Fisheries of the Gulf of Alaska

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion for Biological Opinion National…

Biological Opinion National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources, Permits and Conservation Division, USCG Dock Construction, Seward and Sitka, Alaska

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion for National Marine Fisheries…

Data & Maps

Massachusetts Restricted Area with State Waters Expansion and Wedge Area

Research

On-Demand Gear Guide

A roadmap for providing fishermen an option to use on-demand fishing systems in the Greater Atlantic Region by 2028.

A Trans-Pacific Movement Reveals Regular Migrations of Humpback Whales Megaptera novaeangliae Between Russia and Mexico

Data demonstrating regular trans-Pacific movements of humpback whales in the North Pacific,…

Retrospective analysis of measures to reduce large whale entanglements in a lucrative commercial fishery

Marine mammal bycatch is a significant anthropogenic threat to recovering populations. Gear…

Passive Acoustics Research Group News & Media

Our Passive Acoustics Research Group frequently makes the news. This page links to articles and other media featuring our staff and their research.

Outreach & Education

2025 Long-term Monitoring of Humpback Whale Predation on Pacific Herring in Prince William Sound

Research brief

Research Brief: 2023 Acoustic Survey for Cetaceans in Behm Canal and Southern Clarence Strait, Alaska

The research will be based off of the charter vessel Alaskan Song. The overall research objectives…

Valentine Cards to “Share the Love” for Marine Animals in the Pacific Islands Region

Eight valentine cards with drawings to color, fun facts, and viewing distances for humpback whales,…

Northeast Trap/Pot Guide for Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan

Guide to Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan regulations for Northeast trap/pot fishermen…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024