Veteran commercial fisherman Dave Campo has caught sandbar sharks through a unique fishery focused on research since 2013. But he’s fishing a little differently this year. Instead of using a single line with 300 hooks, he’s spreading those hooks across a series of sets.

It might sound minor. But for Campo and other fishermen in the Atlantic Shark Research Fishery, it’s an example of how industry, fishery managers, and scientists can work together to protect species from overfishing while securing fishing opportunities.

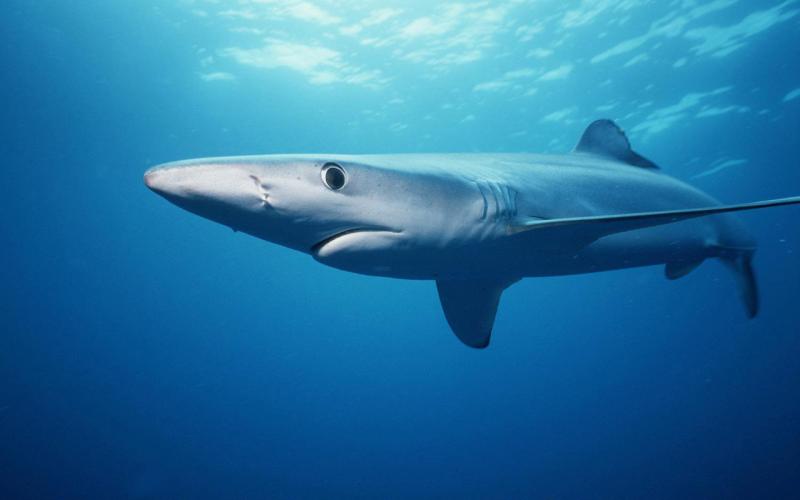

"The more hooks we have on a line, the longer it takes to pull them back in. That increases the chance that a dusky shark caught on the line will die. If that happens too often, the fishery is closed to protect the dusky shark population,” explained Campo. “NOAA Fisheries listened when we told them that we had to be able to run smaller sets to ensure we could fish all year.”

“We are always looking for ways to fish smarter so we can reduce bycatch mortality,” added fisherman Charlie Locke, who has participated in the Shark Research Fishery since 2010.

Fishing for Data

The first batch of fishermen in the Shark Research Fishery took to the water in 2008. Two years before, a stock assessment revealed that the commercially valuable sandbar shark stock was overfished. The annual quota had to be significantly lowered to allow the stock to recover.

The 2006 assessment also demonstrated that data on post-release survival, reproduction, and other life history characteristics for sandbar and other sharks was limited and hard to get.

“It’s very difficult to confidently determine if leaving hooks in the water for a certain amount of time, for example, reduces the chance that a shark will survive if we can’t control other variables and don’t know exactly how long the soaktime was,” said Dr. John Carlson, a research fishery biologist.

NOAA Fisheries seized the opportunity to give fishermen access to the small sandbar quota in the Atlantic while collecting more robust information for future stock assessments.

Since then, 5–7 vessels are allowed to keep a limited number of sandbar sharks each year. The vessels are chosen through an annual application process, and these fishermen are the only ones allowed to land and sell this species.

In exchange, a NOAA Fisheries observer is on board to collect data any time a vessel fishes under their research fishery permit. Participants are currently limited to two fishing days a month. They must also follow restrictions that limit the number and type of interactions they have with the overfished dusky shark stock.

The result is a unique opportunity for scientists—both in and out of NOAA—to study shark genetics, reproduction, behavior, and health with robust data spanning across regions and over time.

“Managing shark populations sustainably is a dynamic process that requires the best available science,” said Cisco Werner, chief science advisor for NOAA Fisheries. “Strong stock assessments play a critical role in establishing management measures that provide optimum yield for fishermen while preventing overfishing and minimizing bycatch.”

Science at Sea

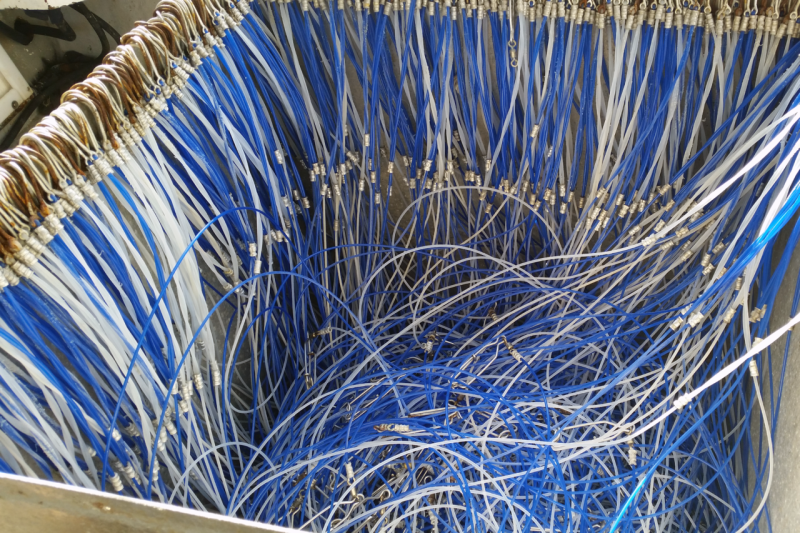

NOAA Fishery observers work hand-in-hand with fishermen to collect data on every caught shark species. As the crew hauls in their line, the observer attaches one of several tag types and estimates the length of any prohibited sharks before they’re cut loose. The tracking results from satellite tags used for released dusky sharks will shine a light on post-release survival rates of that species.

At the same time, the observer records the length of each shark brought onboard before collecting biological samples like reproductive organs and vertebrae. They’ll switch rapidly between tagging and collecting for the roughly 3 hours it takes the crew to pull up the last shark.

“We’ve really learned to work in tandem over the years,” said Locke, who operates a 32-foot boat off the coast of North Carolina. “I don’t fish any differently with them than I would if the observer wasn’t on board.”

Some sharks are set aside to be dressed on the dock. This allows the observer to get an accurate weight of the animals before and after the tail, head, and some organs are removed. NOAA scientists will use the results to ensure that the numbers we get from fishermen and dealers are correctly converted to whole weight before being plugged into stock assessments.

Observers also collect a small sample from the fins of some sharks. Those clips are eventually sent to researchers at the Field Museum of Chicago, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, and the Florida International University for genetic testing. This is one of several partner groups NOAA Fisheries has coordinated with to glean as many insights as possible from this unique fishery.

The other samples are sent to Panama City, Florida. There, NOAA scientists analyze the organs and vertebrae for information on age, growth, and reproduction. That information is later fed into stock assessments.

“The high volume of samples we get from the Shark Research Fishery would be very difficult and slow to collect otherwise because of the size and the large migration range of sharks,” said Carlson. “We’ve been able to demonstrate species characteristics that we just couldn’t do without year-round access to data.”

For example, Carlson and his team discovered in 2010 that a segment of the sandbar shark population reproduces every three years. Biologists had previously believed that all female sandbar sharks had a two-year reproduction cycle.

“This discovery that sandbar sharks are less productive than originally believed will allow us to set more sustainable quotas and develop a more effective rebuilding plan,” said Alan Risenhoover, director of the Office of Sustainable Fisheries. “This will benefit both fishermen and shark populations.”

Data to Decisions

Perhaps the biggest management change to come from the Shark Research Fishery is Amendment 6 to the 2006 Consolidated HMS Fishery Management Plan.

Before this was finalized in August 2015, fishermen could keep up to 36 large coastal sharks per trip. Amendment 6 increased that retention limit to a default of 45 per trip to boost the profitability of fishing trips. It also built in flexibility for managers to adjust the retention limit as needed throughout the season.

These changes were possible in part because of results from the Shark Research Fishery that improved our understanding of how sandbar and other sharks fare after they’re released.

The connection between data collected today and the management measures of tomorrow is what initially drove Campo and Locke to apply for a Shark Research Fishery permit. They’ve seen an increase in the number of sandbar sharks in their regions over the last decade. They expect the research fishery will reveal a stock healthy enough to be fished at higher levels.

“Having observers onboard is great because they can see what I’m seeing every day,” said Campo. “I want NOAA Fisheries to have the best data possible so we can get the sandbar fishery back in place.”

Locke also hopes that the practices to reduce bycatch and increase post-release survival honed in the research fishery can be extended to prevent the need for future prohibitions.

“This is sort of a guinea pig fishery,” said Locke, using a phrase coined by a fellow shark fisherman. “It’s a place where we can find more effective practices and continue the United States’ long history of being a model of sustainable shark management for the rest of the world.”