Chief Scientist’s Weather Report: Scattered boulders and rocks, with increasing cobbles; 100% chance of heavy mud.

On June 24 we returned to Canada and the Northeast Channel for two more dives. Our objectives were the same as before: to define the extent of deep-sea corals and their habitats, and to delineate the boundaries for a possible marine protected area.

Our first dive at the Northeast Channel on June 20 was on the western side of the channel. On June 24 we dove on the east side of the channel, starting at about 940 meters. Both ROPOS and the Bigelow had to fight a wicked current, making sampling difficult. As ROPOS meandered up a slope to about 550 meters, we encountered lots of coral oases.

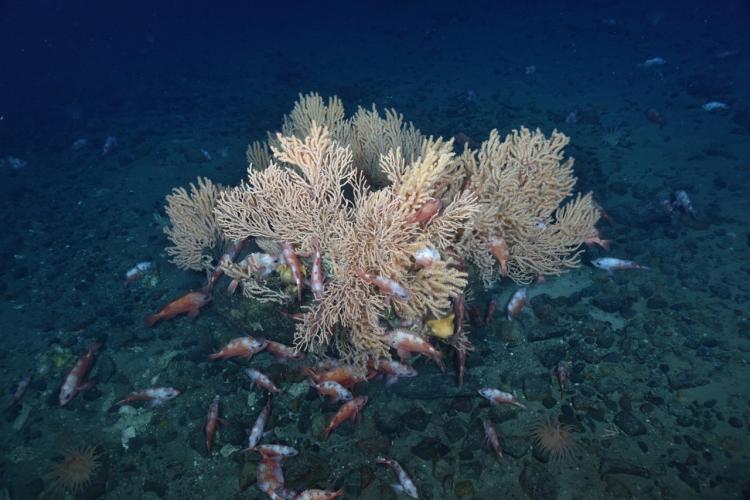

Similar to the previous channel dive, the coral assemblage consisted of bubblegum, Primnoa, and sometimes soft corals on rocks or boulders sticking up from the sediment. There were small, perhaps newly-settled corals on the smaller rocks in the sediment as well.

As we ascended further up onto the ridge, there were fewer coral oases to be seen. At around 440 meters depth, we decided to turn off of our planned ascent and explore down a steep slope. The slope consisted of gravel or cobble “pavement,” with no larger rocks or boulders, and there was little life to be seen. Even the types of fauna one would expect to find in a mud bottom, such as anemones, were absent. It was clear that the highest densities of deep-sea coral were located in the deeper parts of this section of the channel.

Our third and final channel dive, and also the last one of the mission, on June 25 was the furthest east of the three. The bathymetry didn’t look too promising for finding coral habitat, and we weren’t disappointed. We zig-zagged up and down slopes ranging from 730-420 meters, but nowhere did it seem to be conducive for deep-sea corals. We often traversed steep areas of featureless mud, inhabited mostly by anemones and sea pens living in the sediment. Sea pens are actually a type of deep-sea coral, and the ones we saw, Pennatula, are ubiquitous in the muddy bottoms in the Gulf of Maine and environs. Other invertebrates, like shrimps, crabs, and bobtail squid, were also present. Fish such as flounders, skates, and a variety of deep-sea species were also observed. Redfish were especially abundant, and seemed to be everywhere, resting or sleeping on the bottom or in any nook or cranny they could find. These areas were not lifeless. Scattered rocks and boulders characterized some areas, with most boulders hosting anemones. We did find a couple of rocks and boulders that had some small Primnoa, purple soft coral, and others occupying the exposed hard substrate.

And so our last survey ended. We were not unhappy that we didn’t find any deep-sea coral habitats on this last dive, since every observation provides us with important data needed to improve our knowledge of these deep-sea habitats. Overall this was a wildly successful cruise. The seas remained calm throughout, the ROV operations went flawlessly, and we completed all the surveys that we set out to do. Anyone who’s been on a research cruise will tell you how rare that is! There are, of course, many samples to be processed by many scientists, and lots and lots of data to unravel, so the work has only begun. We owe all of this to the fantastic crew of the NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow, the amazing pilots and engineers of the ROV ROPOS, and an incredible team of U.S. and Canadian scientists, led by the indomitable Martha Nizinski and Anna Metaxas.

Dave Packer, NOAA Fisheries Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Aboard the NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow HB1903