Mahimahi fish. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Mahimahi fish. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Mahimahi fish. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Mahimahi fish. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Mahimahi fish. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Mahimahi fish. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Mahimahi are highly sought for sport fishing and commercial purposes. They are pelagic fish found in off-shore temperate, tropical, and subtropical waters worldwide including the Atlantic and Gulf of America (formerly Gulf of Mexico). Mahi are considered a good eating fish, often served in restaurants. As one of the fastest-growing fish in the ocean, they are capable of lengths over 4 feet in the first year of life, and over 6 feet in four years.

Population

The population level is unknown, but management measures are in place.

Fishing Rate

Overfishing status is unknown, but management measures are in place.

Habitat Impact

Fishing gear used to catch mahimahi rarely contacts the ocean floor and has minimal impacts on habitat.

Bycatch

Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch in the tuna and swordfish fisheries that incidentally catch the most commercially available mahimahi.

Population Status

- Although the population is not formally assessed and the overfishing and overfished status are unknown, scientists assume mahimahi populations are stable because the species is highly productive and widely distributed throughout the tropical/subtropical Pacific.

- Mahimahi can handle relatively high fishing rates, but precautionary management seeks to maintain current harvest levels.

Appearance

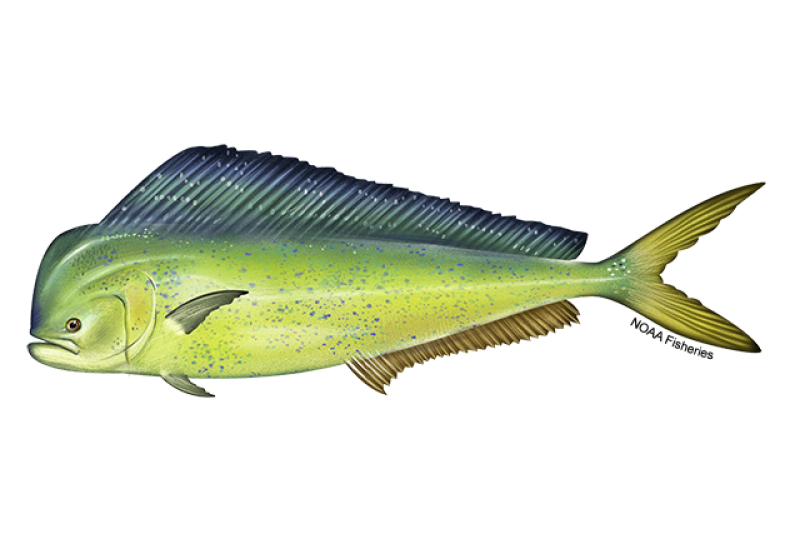

- Brightly colored back is an electric greenish blue, lower body is gold or sparkling silver, and sides have a mixture of dark and lights spots.

- Bright pattern fades almost immediately after mahimahi is harvested.

- Distinguished from the pompano dolphin by the number of dorsal fin rays and a very wide, square tooth patch on the tongue.

Biology

- Pacific mahimahi grow fast, up to 7 feet and 88 pounds.

- They live up to 5 years.

- They are capable of reproducing at 4 to 5 months old.

- They are believed to spawn every 2 to 3 days throughout their entire spawning season (perhaps year-round), releasing 33,000 to 66,000 eggs each time.

- Pacific mahimahi are top predators that feed in surface waters during the day.

- They eat a wide variety of species, including small pelagic fish, juvenile tuna, invertebrates, billfish, jacks, pompano, and pelagic larvae or nearshore, bottom-living species.

- Predators include large tuna, marine mammals, marlin, sailfish, and swordfish.

Where They Live

Range

- Pacific mahimahi are found in the Pacific and Western Pacific and are caught from California to Hawaii and the U.S. Pacific Island territories.

- Most of the U.S. commercial harvest of Pacific mahimahi comes from Hawaii.

Habitat

- Pacific mahimahi live near the surface in tropical and subtropical waters around the world.

- They swim together in schools as juveniles, but older fish are usually found alone.

- They travel seasonally as adults with changes in water temperature.

Fishery Management

- NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery on the West Coast.

- Managed under the Fishery Management Plan for U.S. West Coast Fisheries for Highly Migratory Species:

- Commercial fishermen must have permits and maintain logbooks.

- Gear restrictions and operational requirements.

- NOAA Fisheries and Western Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery in the Pacific Islands.

- Managed under the Fishery Ecosystem Plan for the Pelagic Fisheries of the Western Pacific:

- Commercial fishermen must have permits and maintain logbooks.

- Longlines are prohibited in certain areas to protect endangered Hawaiian monk seals and reduce the potential for gear conflicts and localized stock depletion.

- Longline fishermen must carry a vessel monitoring system—a satellite transponder that provides real-time position updates and tracks vessel movements to enforce regulations.

- In Hawaii and American Samoa longline fishermen must also carry onboard observers when requested.

- Longline vessel owners and operators are required to attend annual protected species workshops.

- There are no management measures specific to mahimahi, because catch trends indicate that regulations are not necessary.

Harvest

- Commercial fishery:

- U.S. commercial fisheries in the western and central Pacific harvest the majority of U.S. mahimahi.

- In 2023, commercial landings of Pacific mahimahi harvested from the U.S. Pacific Islands and the West Coast totaled approximately 900,000 pounds and were valued at $3.2 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. The majority of the catch comes from Hawaii.

- Gear types, habitat impacts, and bycatch:

- Most mahimahi are harvested using troll and handlines. Mahimahi may also be caught incidentally in pelagic longline fisheries for tuna and swordfish.

- The amount of bycatch associated with the mahimahi fishery varies. U.S. pelagic longline fishermen, who target tuna and swordfish and who may incidentally catch mahimahi, are required to use specific tools and handling techniques to mitigate bycatch of turtles and marine mammals.

- Fishing gear used to catch mahimahi rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal.

- Time-area closures also limit and prevent interactions between pelagic longline gear and non-target species.

- Onboard observers are required in some fisheries to record any interactions with sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals.

- Recreational fishery:

- Pacific mahimahi are a popular recreational fish.

- In 2023, recreational fishermen harvested 3.6 million pounds of mahimahi in the U.S. Pacific Islands, according to the NOAA Fisheries recreational fishing landings database.

Scientific Classification

- Pacific mahimahi are found in the Pacific and Western Pacific and are caught from California to Hawaii and the U.S. Pacific Island territories.

- Most of the U.S. commercial harvest of Pacific mahimahi comes from Hawaii.

- Pacific mahimahi live near the surface in tropical and subtropical waters around the world.

- They swim together in schools as juveniles, but older fish are usually found alone.

- They travel seasonally as adults with changes in water temperature.

Fishery Management

- NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery on the West Coast.

- Managed under the Fishery Management Plan for U.S. West Coast Fisheries for Highly Migratory Species:

- Commercial fishermen must have permits and maintain logbooks.

- Gear restrictions and operational requirements.

- NOAA Fisheries and Western Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery in the Pacific Islands.

- Managed under the Fishery Ecosystem Plan for the Pelagic Fisheries of the Western Pacific:

- Commercial fishermen must have permits and maintain logbooks.

- Longlines are prohibited in certain areas to protect endangered Hawaiian monk seals and reduce the potential for gear conflicts and localized stock depletion.

- Longline fishermen must carry a vessel monitoring system—a satellite transponder that provides real-time position updates and tracks vessel movements to enforce regulations.

- In Hawaii and American Samoa longline fishermen must also carry onboard observers when requested.

- Longline vessel owners and operators are required to attend annual protected species workshops.

- There are no management measures specific to mahimahi, because catch trends indicate that regulations are not necessary.

Harvest

- Commercial fishery:

- U.S. commercial fisheries in the western and central Pacific harvest the majority of U.S. mahimahi.

- In 2023, commercial landings of Pacific mahimahi harvested from the U.S. Pacific Islands and the West Coast totaled approximately 900,000 pounds and were valued at $3.2 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. The majority of the catch comes from Hawaii.

- Gear types, habitat impacts, and bycatch:

- Most mahimahi are harvested using troll and handlines. Mahimahi may also be caught incidentally in pelagic longline fisheries for tuna and swordfish.

- The amount of bycatch associated with the mahimahi fishery varies. U.S. pelagic longline fishermen, who target tuna and swordfish and who may incidentally catch mahimahi, are required to use specific tools and handling techniques to mitigate bycatch of turtles and marine mammals.

- Fishing gear used to catch mahimahi rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal.

- Time-area closures also limit and prevent interactions between pelagic longline gear and non-target species.

- Onboard observers are required in some fisheries to record any interactions with sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals.

- Recreational fishery:

- Pacific mahimahi are a popular recreational fish.

- In 2023, recreational fishermen harvested 3.6 million pounds of mahimahi in the U.S. Pacific Islands, according to the NOAA Fisheries recreational fishing landings database.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Actinopterygii | Order | Carangiformes | Family | Coryphaenidae | Genus | Coryphaena | Species | hippurus |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/17/2025

Featured News

Celebrate Culinary Arts Month with a sustainable seafood recipe for every month of the year.

Celebrate Culinary Arts Month with a sustainable seafood recipe for every month of the year.

What Your Birth Month Says About Your Next Seafood Recipe

Coral nurseries are one tool NOAA uses to restore reefs, which are vital habitats for many managed seafood species. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Coral nurseries are one tool NOAA uses to restore reefs, which are vital habitats for many managed seafood species. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Seafood Facts

Is Pacific Mahimahi Sustainable?

U.S. wild-caught mahimahi is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations.

Availability

Year-round.

Source

U.S. wild-caught from Hawaii, California, U.S. Pacific Island territories, and on the high seas.

Taste

Mahimahi has a sweet, mild flavor. For a milder flavor, trim away the darker portions of the meat.

Texture

Mahimahi is lean and fairly firm with large, moist flakes.

Color

The raw flesh is pinkish to grayish-white, although along the lateral line the flesh is dark. When cooked, the meat is off-white.

Health Benefits

Mahimahi is low in saturated fat and is a good source of vitamin B12, phosphorus, potassium, protein, niacin, vitamin B6, and selenium.

Nutrition Facts

Servings: 1; Serving Weight: 100 g (raw); Calories: 85; Protein: 18.5 g; Total Fat: 0.7 g; Total Saturated Fatty Acids: 0.188 g; Carbohydrate: 0 g; Total Sugars: 0 g; Total Dietary Fiber: 0 g; Cholesterol: 73 mg; Selenium: 36.5 mcg; Sodium: 88 mgMore Information

Mahimahi (Mahi Mahi) Recipes

Looking for some ways to add mahimahi into your rotation? If you need some cooking inspiration, browse these recipes for grilled mahimahi, steamed citrusy mahimahi, and more!

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/17/2025

Seafood News

Celebrate Culinary Arts Month with a sustainable seafood recipe for every month of the year.

Celebrate Culinary Arts Month with a sustainable seafood recipe for every month of the year.

What Your Birth Month Says About Your Next Seafood Recipe

Fresh-caught taʻape on ice. Credit: Conservation International Hawaiʻi.

Fresh-caught taʻape on ice. Credit: Conservation International Hawaiʻi.

Reducing Waste and Feeding Communities in Hawaiʻi with a Whole Fish Approach

Chef Tyler Hadfield’s Curried Skate Wings with Tomato-Masala Chutney

Chef Tyler Hadfield’s Curried Skate Wings with Tomato-Masala Chutney

Ring In the New Year With These Crowd-Favorite Seafood Recipes

NOAA Fisheries, in collaboration with Blue Ocean Mariculture, is conducting a multi-year pilot study to evaluate observational methods and tools for studying Hawaiian monk seal behavior. Courtesy of Blue Ocean Mariculture

NOAA Fisheries, in collaboration with Blue Ocean Mariculture, is conducting a multi-year pilot study to evaluate observational methods and tools for studying Hawaiian monk seal behavior. Courtesy of Blue Ocean Mariculture

AI Meets Aquaculture to Study Hawaiian Monk Seal Interactions With Net Pens

Documents

Diet Analysis of Mahimahi (Coryphaena spp.) Caught On Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, Using DNA Barcoding

This study provides evidence that mahimahi consume a wide variety of prey taxa that spans multiple…

Data & Maps

American Samoa Longline Logbook Reports 2023

Logbook summary reports for the 2023 calendar year.

American Samoa Longline Logbook Reports 2022

Logbook summary reports for the 2022 calendar year.

Hawaii and California Longline Logbook Reports 2022

Logbook summary reports for the 2022 calendar year.

Hawaii and California Longline Logbook Reports 2021

Logbook summary reports for the 2021 calendar year.

Research

Fishery Monitoring for West Coast and International Fisheries

We transform fisheries data into fisheries information via summations and statistical analyses to support stock assessments, scientific studies, and national and international data reporting requirements.

Relative Impacts of Simultaneous Stressors on a Pelagic Marine Ecosystem

Model suggests that due to climate change, a decline in the yield of Hawaii's longline fishery may…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/17/2025