As the first NOAA large whale survey in the Gulf of Alaska since 2015 wrapped up, scientists had two extraordinary encounters. They saw and were able to collect valuable information on four North Pacific right whales south of Kodiak Island, Alaska.

North Pacific right whales are among the most endangered animals in the world with fewer than 100 individuals estimated remaining. The species was heavily exploited by Russian whaling in the 1960s. Only an estimated thirty individuals make up the Eastern stock that inhabits Alaska waters. A population of whales can be made up of different stocks depending on genetic characteristics or morphological (biological) differences or for management purposes. There are two stocks of North Pacific right whales, one in the eastern Pacific and one in the western Pacific.

Scientists were thrilled to find two separate pairs of right whales, just 3 days apart. With so few animals remaining in the population, seeing more than one animal at a time is remarkable.

The team was able to collect photos, video, and audio of the four whales. They identified two of the whales from previous sightings, which were both exciting and encouraging indications that these rare whales could be observed and tracked over time. One of the animals, from the first pair of whales sighted, was seen earlier this summer in Canadian waters. Another animal in the second pair of whales sighted was seen during a 2006 NOAA survey in the Gulf of Alaska near Barnabas Trough.

A Much-Needed Whale Survey

The sightings occurred during a month-long survey of the Gulf of Alaska, which is part of the Pacific Marine Assessment Program for Protected Species (PacMAPPS). This is a multi-agency effort to collect abundance and distribution information on whales and other species in U.S. waters.

The Gulf of Alaska is a habitat for many endangered marine mammal species, both as a migratory thoroughfare and as an important feeding ground. It also is an area of growing interest for human activities including fishing, shipping, oil and gas exploration, and military exercises.

NOAA Fisheries and the U.S. Navy supported this survey to improve our understanding of the distribution and density of whales in this important marine habitat.

To collect information on North Pacific right whales and other species, researchers used the NOAA research vessel Oscar Dyson to conduct a series of transects or “straight” survey lines. All whales, porpoises and dolphins encountered along each transect were counted. From these data, scientists will be able to estimate the distribution and abundance for the whale, porpoise and dolphin species within the area.

Researchers documented a total of 667 sightings of marine mammals, some of which were duplicate sightings of the same animal, during the survey. Primary species sighted included fin, humpback, killer, and sperm whales, and Dall’s and harbor porpoise.

“We collected valuable information on several whale species including killer whales,” said Kim Goetz, marine mammal biologist, Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “From this we were able to identify whether they were resident or transient killer whales.”

Killer whales are top predators, with complex social structures. Resident killer whales in Alaska feed exclusively on fish—mainly salmon—while transient whales eat marine mammals and squid. Resident killer whales remain relatively local in mostly coastal waters. Transient orcas move north and south along the coast from Southeast Alaska and British Columbia to as far south as Southern California.

Locating the Endangered North Pacific Right Whale

Marine mammal scientists were transecting the eastern North Pacific right whale’s critical habitat. They were hopeful that they might be lucky enough to come across at least one of these elusive giants too.

From the deck of the research vessel, marine mammal observers, equipped with high-powered binoculars, spotted the blows from two right whales. Right whales have a distinct v-shaped blow.

“The two whales were feeding together in Barnabas Trough, which is about 25 nautical miles south of Kodiak Island near Albatross Bank,” said Crance. “This is a highly productive area of the Gulf of Alaska, known for having high densities of krill and other baleen whale prey. The abundance of prey is due to upwelling, which provides nutrient rich water from the canyon depths. It’s an area where right whales have been seen in the past.”

The most important tool for identifying individual whales is the photograph. Right whales are distinguished by growths on their heads called callosities. The pattern of callosities on each animal is as unique as a fingerprint.

With good photographs of the right and left side of each animal’s head, scientists matched one of the animals to a catalogue of existing photos. It was the same animal seen by a Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans scientific team on June 12 off Haida Gwaii in British Columbia, Canada.

While in Barnabas Trough, the scientists also recovered and redeployed a long-term bottom-mounted passive acoustic mooring that records sounds like whale calls. Recordings collected year-round will be downloaded from the acoustic equipment attached to the mooring. Scientists will analyze the recordings to identify sounds made by whales and other species to learn more about their movements through the area.

About 100 miles to the west, outside the critical habitat, and about 30 nautical miles south of the Trinity Islands, the scientists encountered two more North Pacific right whales.

“We used passive acoustic equipment, in this case sonobuoys, containing a hydrophone that allowed us to listen for right whale sounds in real time. We followed the sound to get bearings and help us locate the animals,” said Crance. “The equipment wasn’t just helpful for finding the whales but also for recording their song.”

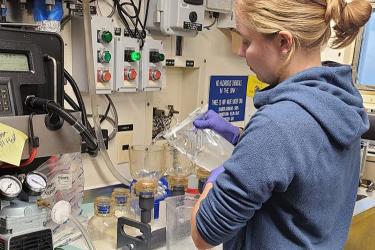

NOAA Fisheries scientist Jessica Crance deploys a sonobuoy to acoustically monitor for North Pacific right whale calls.

Of the three right whale species—the Atlantic, the southern and the North Pacific—only the North Pacific right whale is known to sing. Crance was the first to discover this remarkable behavior in 2010.

“A right whale song isn’t like the melodic calls of the more familiar humpback whale. It’s more like a series of repetitive, stereotyped calls. Songs primarily consist of gunshot calls, but also may include upcalls and moans,” added Crance.

Hear: Song Recording 1 GS2-TP

Hear: Song Recording 2 GS3-PU

(Listen carefully in the beginning to hear the faint growling sound and progression of calls)

Since the whales didn’t spend much time at the surface, collecting photographs was more challenging than it had been for the first two whales encountered.

“The whales were only taking one or two short breaths before diving, and weren’t lifting their heads very far out of the water,” said Crance.

Ultimately the team was able to get several good photos. Only one of the second pair of animals had been observed before. The other was not matched to the catalogue.

The team also collected oceanographic information throughout the survey. Every evening, the scientists conducted measurements of the water column temperature and salinity. They collected water samples down to a maximum depth of more than 3,000 feet to learn more about environmental conditions of the local habitat.

Science Center fisheries biologists also helped the team to use acoustic equipment to collect data that can be used to detect and map the distribution of krill. This equipment uses active acoustic soundwaves to estimate local densities of prey fields. From this, scientists can gain insights on possible whale diet and food availability.

“The ability to link marine mammals to prey resources and oceanographic features will enable us to better understand how these animals interact with their environment and the drivers behind their movement and distribution,” said Crance.

Urgency to Learn More about North Pacific Right Whale Movements

Migratory patterns and calving grounds of eastern North Pacific right whales are unknown. It is thought that they migrate from high-latitude feeding grounds in summer to more temperate waters during the winter, possibly offshore. Scientists documented this movement in one North Pacific right whale which travelled the distance from the Bering Sea to Hawaii.

Sightings of North Pacific right whales have been reported as far north as the sub-Arctic waters of the Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk off Russia in the summer. The farthest south they have been observed is in central Baja California in the eastern North Pacific and Hawaii in the central North Pacific.

The little information scientists do have was collected primarily from whales in the Bering Sea.

However, in 2005, researchers from the Alaska Fisheries Science Center photographed a juvenile North Pacific right whale in the Gulf of Alaska Critical Habitat Area. Seeing a juvenile was heartening to the team: a sign that the whales were breeding. After this year’s survey, scientists confirmed that the right whale observed in 2005 didn’t match any of the right whales seen this summer.

Analysis of images, video, and audio recordings from this year’s survey will add to the scientific community’s collective understanding of right whale behavior and movement patterns.

Scientists hope that passive acoustics research, combined with vessel or aerial surveys, if regularly conducted, can reveal more about the few remaining North Pacific right whales and help aid their recovery.

"We are grateful to the Navy and all our partners for their help getting this year's survey off the ground," added Robyn Angliss, Cetacean Assessment and Ecology Program Manager for the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. "Comprehensive surveys like this, together with passive acoustics, are needed to learn as much as we can about endangered North Pacific right whales, and other marine mammals in Alaskan waters for which we have limited data on abundance, whether their populations are increasing or decreasing and their seasonal patterns of distribution. Our hope is that this will be the first of a series of rotating surveys of cetaceans in Alaska to fill these critical information gaps."

Editor's Note: Colleagues in the marine mammal programs at the NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, Northeast Fisheries Science Center and Southeast Fisheries Science Center graciously provided advice on software, hardware, installation of equipment, and survey protocols, and the Southwest Fisheries Science Center loaned key equipment without which the survey could not have been successful. The team extends their deep appreciation to the observers who collected the data and to the officers and crew of the NOAA research vessel Oscar Dyson who enabled an effective and safe survey. Alaska Fisheries Science Center administrative staff set a new bar for speedy processing of agreements needed to enable the project. The U.S. Navy provided funding and the sonobuoys used to record cetacean calls and to locate the second North Pacific right whale sighting. Thank you, all, for your roles in the team’s success.