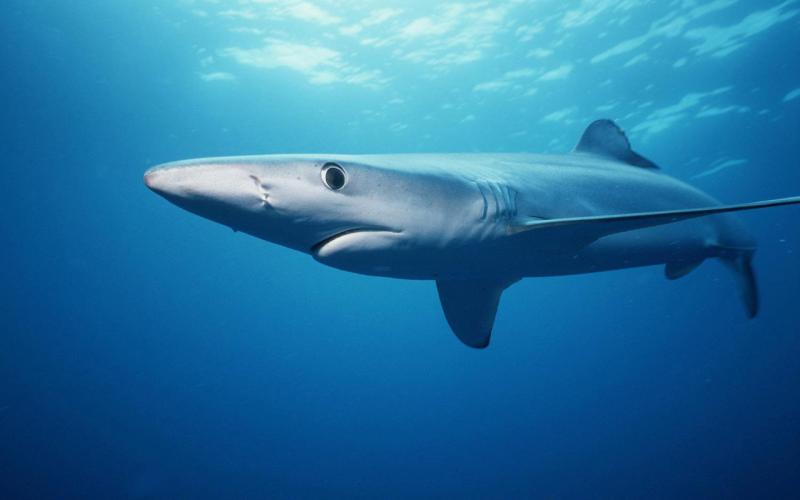

The waters off the East Coast are home to more than 50 shark species. These range from the small spiny dogfish to the much larger white shark, and they are found in just about every kind of ocean habitat.

Species Commonly Found Near Shore

Most Atlantic sharks spend at least part of their lives in coastal waters. Many species move through bays and estuaries along the U.S. coast in search of food. Others are open-ocean dwellers that use shallower waters as nurseries or occasional feeding grounds.

Species like Atlantic blacktip, spinner, and Atlantic sharpnose sharks can be abundant in the Southeast’s and Gulf of America’s nearshore waters. In the Caribbean Sea, tiger, hammerhead, and Caribbean reef sharks are often seen. In the Mid-Atlantic region, sandbar, sand tiger, and smooth dogfish sharks frequent nearshore waters, especially during the summer. These species are also found in New England waters, where spiny dogfish and white sharks commonly swim in search of their natural prey.

Explore Atlantic shark nurseries

Interactions with Humans

It is extremely unlikely for Atlantic swimmers and surfers to be bitten by—or even encounter—a shark. The University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File recorded a worldwide total of 108 interactions, with 41 unprovoked shark bites in the United States in 2022. Explore the International Shark Attack File to learn more about:

- Trends in shark interactions

- Where shark interactions occur in the United States

- Shark interactions compared to other risks

Watch the video below to learn how swimmers and surfers concerned about sharks can further reduce the chances of being bitten.

Recovering Populations

Fishing and other human activities in the 1980s and early 1990s significantly lowered some Atlantic shark populations. Today, we manage 43 species of sharks in Atlantic federal waters with rules that prevent overfishing and rebuild overfished stocks. Thanks to this science-based approach, several shark stocks have experienced population growth including:

- Atlantic sharpnose

- Atlantic blacktip

- Sandbar

- Spiny dogfish

- Tiger

- White

Are all U.S. sharks overfished?

Hear from our researchers on white shark recovery