Steelhead returns to the Snake River and Chinook and chum salmon runs on the Yukon-Kuskokwim River in Alaska in 2021 were among the lowest on record. Returns of steelhead to some tributaries of the Fraser River in Canada fell close to extinction levels.

Meanwhile, a bumper coho catch was the talk of the Oregon Coast. Bristol Bay in Alaska recorded the greatest return of sockeye salmon on record.

The disparity of 2021 returns among West Coast and Alaska salmon and steelhead reflects the tremendous influence of ocean conditions to affect fish survival. Temperature, currents, prey availability, and nutrients affect West Coast fish stocks differently depending on their size and health when entering the ocean and where they spend their time.

The way they use the ocean helps determine their success as predators and whether they become prey. That affects the likelihood of recovery for the more than 25 species of threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead on the West Coast.

The ocean is the most remote and hardest part of their life cycle to study, leaving it the least understood chapter. This is especially true for smaller regional populations such as Snake River steelhead, which may be spread across thousands of miles of ocean. “Trying to find them on the high seas is like looking for a needle in a marine haystack,” said Laurie Weitkamp, research biologist at NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

Scientists Begin Winter Survey

Weitkamp will soon help lead an international expedition into the stormy northern Pacific Ocean. She shares the role of chief scientist of the survey with Ed Farley, a research scientist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. They will investigate where salmon from around the Pacific Rim go in the ocean and what affects them there. The 2022 Pan-Pacific Winter High Seas Expedition will include vessels and salmon researchers from the United States, Canada, Japan, and the Russian Federation.

The research survey will probe the North Pacific marine ecosystem and learn more about how it affects salmon and other species. The NOAA research ship Bell M. Shimada, Canadian research vessel Sir John Franklin, the Russian research vessel TINRO, and a chartered commercial fishing vessel, the R/V Raw Spirit, will each examine different areas of ocean.

Scientists aboard will use the latest research technologies—including genetic analysis and environmental DNA —to determine the home rivers of individual salmon they encounter and to check for salmon predators. Slocum gliders will demonstrate the operational readiness of autonomous underwater vehicle-based ecosystem monitoring.

Strong but Variable Effects

Salmon scientists have long recognized the prominent but highly variable effects of ocean conditions on salmon and steelhead. More than a decade ago, researchers at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center developed a color-coded “stoplight chart.” It ranks the marine factors known to affect salmon returns, sometimes positively, and other times negatively.

Many of the indicators have turned more positive over the last year, reflecting cooler ocean conditions that usually improve the productivity of the food web that supports salmon. Scientists noted they were the second-best set of conditions they have seen in the 24 years of tracking them.

Most knowledge of salmon in the ocean comes from coded wire tags recovered from fish when they are caught, and more recently, from their DNA. Both let scientists trace the river or hatchery the fish came from.

Perhaps the most critical period for salmon and steelhead is their first summer at sea, Weitkamp said. Their growth in those early months can bestow a survival advantage in their subsequent years prowling the more remote ocean.

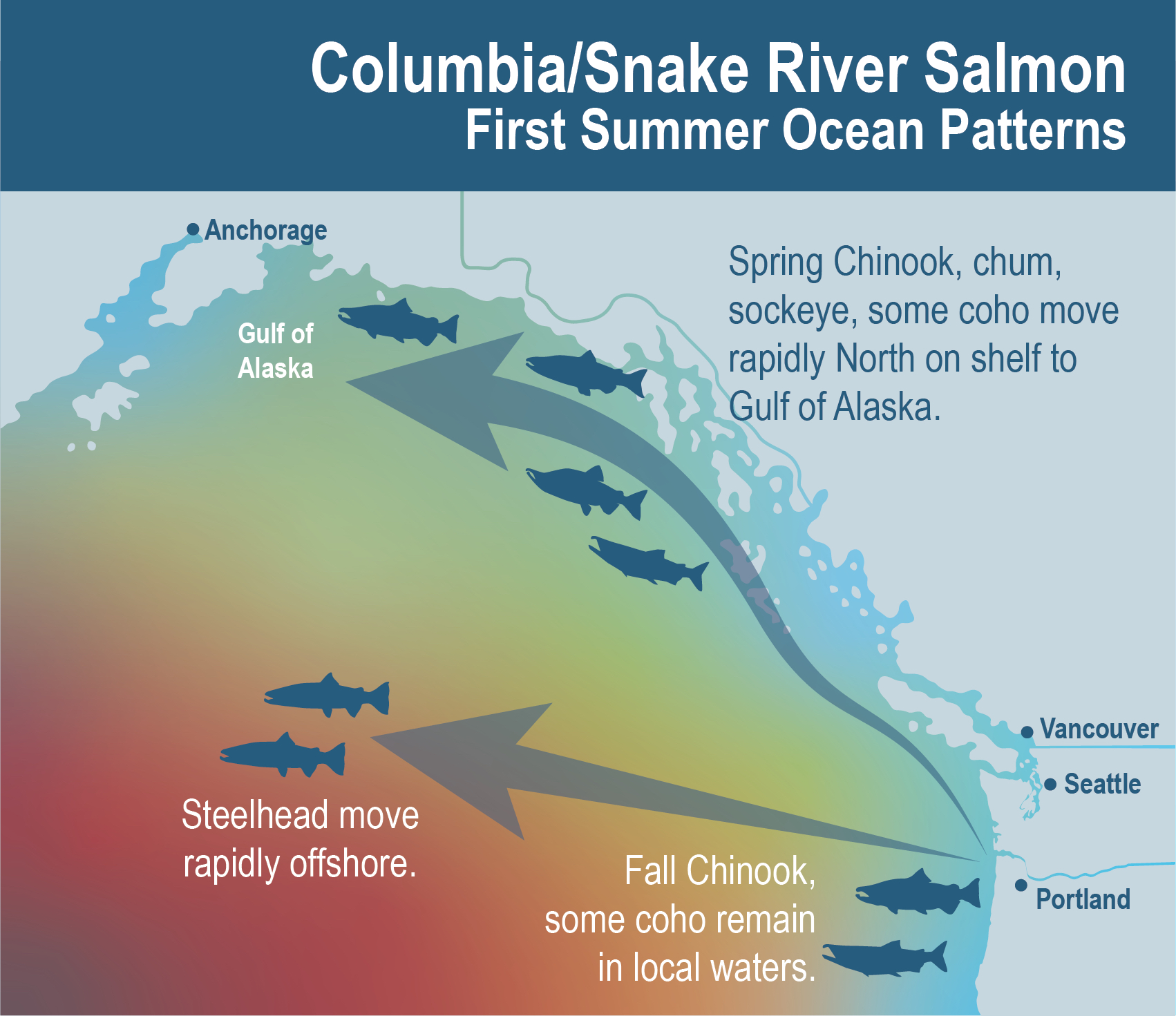

Columbia and Snake River spring Chinook, chum, sockeye, and some coho salmon appear to move quickly north along the continental shelf towards the Gulf of Alaska, for instance. In contrast, fall chinook and some other coho salmon spend much of their first summer in coastal waters. They may benefit from productive upwelling of nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean.

Recent research tracing DNA from the salmon prey of endangered Southern Resident killer whales revealed a kind of salmon superhighway along the West Coast. Salmon from different rivers as far south as Central California and as far north as Alaska travel along the productive coastal shelf.

Heatwaves Depress Productivity

Steelhead have had a harder time, likely because they move offshore so quickly. They thrive when the northern Pacific is in a colder, more productive state. In recent years, though, their migration has put them in the middle of marine heatwaves that reduced productivity. The sparse food web in such warm waters leaves the growing steelhead with less to eat.

“Steelhead are thought to leave the rivers and head far offshore, perhaps almost across the ocean to Kamchatka, Russia,” Weitkamp said. For steelhead, “we think elevated sea surface temperatures have resulted in a food web that isn't particularly productive, either with regards to suitable prey or the food web as a whole.”

These recent marine heatwaves have led to low returns for steelhead from northern British Columbia to California. Nearshore-oriented stocks, like Washington and Oregon coho salmon, had a thin sliver of productive habitat in 2020 and 2021 that helps explain how they were abundant in 2021, said Nate Mantua, a research scientist at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

“The recent marine heatwave in 2014-2016 and continued warm temperatures in 2018-2019 in the Gulf of Alaska led to a collapse of the spring/summer food web on the shelf that likely impacted juvenile salmon growth and survival. Also, we are seeing negative impacts on western Alaska juvenile Chinook and chum salmon fitness during recent above average warm conditions 2016-2019 in the northeastern Bering Sea shelf,” said Ed Farley, Ecosystem Monitoring and Assessment Program Manager, Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Farley hopes this winter’s survey will provide some baseline information for better understanding salmon survival for fish that migrate from rivers throughout Alaska to overwinter in the Gulf of Alaska.

As tough as things have been for steelhead, the stronger returns of coho made for great fishing on the Oregon Coast. Weitkamp is based at a research station in Newport, Oregon, and heard plenty of tales of anglers catching their limits of coho.

“Pacific salmon are known for their diversity of freshwater traits, such as size and age at maturity, and spawn timing and location,” she said. “However, recent marine heatwaves have emphasized diversity in their use of ocean habitats, too. Ocean habitats used by some salmon and steelhead populations have apparently been productive despite the heat waves, but others, not so much.”