Chief Scientist’s Weather Report: Today S to SE winds 5-10 knots, with areas of fog. Seas 2 to 3 feet. For the weather during the past 1,000 years, please consult your local deep-sea coral.

One of the research objectives of the 2019 Bigelow/ROPOS mission is to find and collect specimens of deep-sea corals from the continental slope off Georges Bank for use in climate reconstructions. We know that several species of coral that inhabit this region can live for hundreds of years. They also lay down annual growth rings, much like tree rings. This combination of long life spans and annual growth rings makes for an invaluable archive of ocean climate. Quite simply, there are no other archives of comparable length and resolution for the open ocean. One of the challenges, however, is to find suitable specimens of coral, and to collect them with minimal damage to the surrounding habitat.

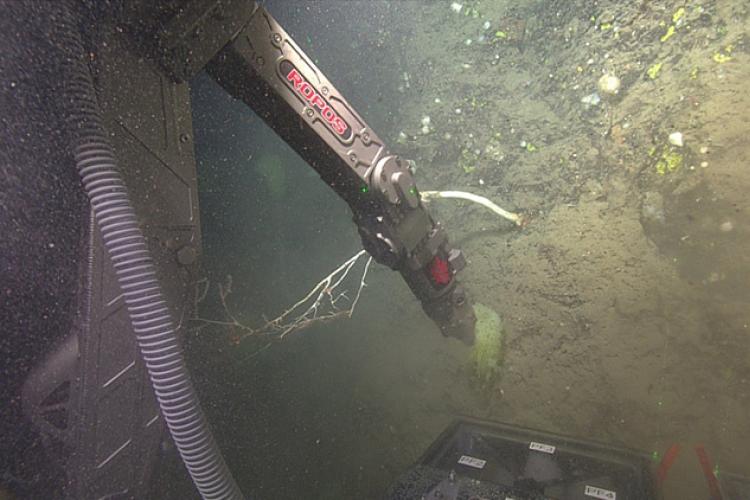

On our dive into an unnamed minor canyon between Nygren and Kinlan canyons we saw many large colonies of bamboo coral growing outward from sheer vertical cliffs of basalt bedrock, at depths of around 1000 meters. We came across one particular large colony that had lost most of its live tissue cover – a telltale sign that the colony was dying. ROPOS pilots maneuvered the ROV into position and used its manipulator arms to gently remove the colony from the cliff face and stow it onboard.

When we recovered the specimen on the Bigelow, we were amazed to see how big it was. ROPOS is equipped with laser scales for taking measurements, but it is difficult to appreciate size on a display monitor. The specimen measured 1.5 meters in length (about 5 feet) and over 4 centimeters (more than 1.5 inches) in diameter, one of the largest ever found in the Northwest Atlantic. Based on known growth rates, this specimen may have lived for 400 years!

Back in the lab, we will use a computerized micro-mill to sample the annual growth rings of this coral. Radiocarbon dating will be used to confirm its precise age. As a geochemist, I have a particular interest in the composition of the organic ‘joints’ spaced along the length of the skeleton and giving this species the appearance of bamboo, from which it gets its name. The organic material is derived, ultimately, from phytoplankton in the surface waters of the ocean, which then sink and feed the corals.

In my lab at Dalhousie, and in collaboration with the McMahon Ocean Ecogeochemistry Lab at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, we are using new analytical techniques to measure stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen within the amino acids that constitute the organic joints of the coral skeleton. These data will generate new information on how the marine ecosystem of the Northwest Atlantic responds to changes in ocean temperature and nutrients over long time periods. Given the rapid rate of ocean warming in the Gulf of Maine region, this information will be critical for predicting what the ocean ecosystem will look like in the future.

Owen Sherwood, Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia

Aboard the NOAA Ship Henry B. Bigelow HB19-03