One of the primary goals for a ship-based survey like the Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey (HICEAS) is to collect the data we need to estimate abundance (population size) for each cetacean (whale or dolphin) species found in Hawaiian waters. To that end, each time we sight a cetacean group, we promptly divert the ship toward the group in order to confirm what species we’ve encountered and to count the number of individuals in the group. Once we have the basic data we need for abundance estimation, we often take identification photos and collect small tissue samples to better understand the range, structure, and health of the population. We follow this protocol every day with every group of each species we find… with the exception of the false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens), who require a different approach to data collection.

False killer whales are highly social and often hunt large pelagic fish (e.g., tunas, mahi-mahi, and billfishes). Research on false killer whales in the main Hawaiian Islands has revealed the tendency of these whales to associate in small coordinated subgroups that can span tens of miles. These smaller subgroups of false killer whales coordinate to search for prey across a broader area and then come together as a group to share their catch. The larger groups often consist of animals that are related or that have been associated with each other for many years–perhaps like your family and the friends in your neighborhood. However, this tendency of false killer whales to occur in small subgroups spread out over a large area meant our survey team had to change the way we work with false killer whale groups when they are encountered, so that the data we collect are better suited for estimating abundance. Instead of treating each group as the detection unit like we do for all other species, we focus instead on the subgroups, using a very specific protocol to get the data we need in the least biased way possible. We call it the Pseudorca Protocol–a name innocuous enough on paper, but one that seems to increase the blood pressure of every person on the ship once it is uttered. This two-phased protocol tests the will and comradery of the science team, temporarily pitting the cetacean observers and acousticians against each other, and requires patience from the ship’s personnel, who must maintain their operations against a backdrop of nerve-wracking data collection.

False killer whales evolved to use subgroups to maximize their feeding success; false killer whale researchers evolved to use the Pseudorca Protocol to maximize their data collection success. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Mark Cotter (Permit #20311)

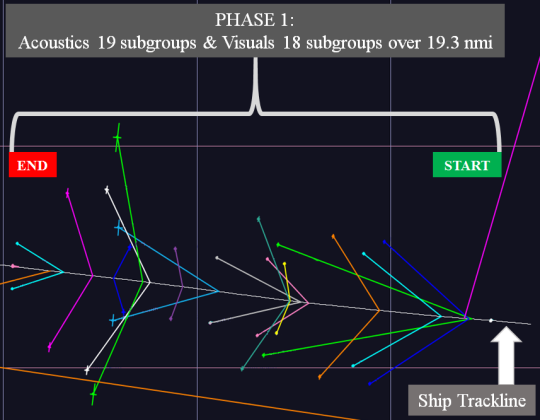

When we see a false killer whale, rather than diverting the ship to assess the group like we would for all other species, we remain on our survey transect (or trackline), recording the position of each subgroup as we pass by. We call this “Phase 1” of the Pseudorca Protocol. We learned from previous surveys that turning toward the first subgroup we see in an attempt to count all individuals in the entire group creates a bias in our data set. That is, false killer whale subgroups are generally separated by large enough distances that the group itself does not conform to the theoretical framework of line-transect sampling, the method we use to estimate abundance. The line-transect method treats aggregations of animals as if they occupy a single point (defined as the center of the grouping) off the trackline. It works by allowing us to use the sightings we made within a certain distance (in our case, three nautical miles) of the trackline as a basis for estimating the abundance of that species in the entire study area. If we venture miles from our trackline counting individuals that were not among those we initially saw, then we are essentially double-counting those animals. To counteract this bias, we remain on the trackline during Phase 1, with the visual and acoustics teams working independently to detect false killer whale subgroups. More often than not, the acoustic team hears false killer whales before the visual team sees them. This could be due to the distance of each subgroup, challenging viewing conditions, sneaky behavior of the animals, or all of the above. In these cases, the observers don’t even know that Phase 1 has begun, as the acousticians are not allowed to tell the observers because doing so would risk influencing their sighting process.

Acoustic detections of false killer whale subgroups during Phase 1 of the Pseudorca Protocol that took place on September 12, 2017, off the south side of Kauaʻi. This Phase 1 lasted two hours and spanned 19.3 nautical miles of trackline, resulting in 19 acoustic and 18 visual detections of false killer whale subgroups. Acoustic detections of successive subgroups are separated by color and shown on both sides of the ship’s trackline because we can’t differentiate left or right with our linear towed hydrophone array. Error bars at the end of each subgroup localization show the confidence in the location. The first violet and last orange locations are very uncertain, but the remaining 17 localizations are very accurate. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Jennifer Keating

Phase 1 of the Pseudorca Protocol ends when the ship has passed through all the false killer whale subgroups along the trackline. The ship then turns back around and is directed by the acoustics team through the highest concentration of subgroups so that the cetacean observers can get a better count of the number of individuals in as many subgroups as possible. We call this “Phase 2” of the Pseudorca protocol. The drawback of Phase 1 is that because we are in ‘passing mode,’ when the ship does not leave the trackline for sightings, we are not able to focus on getting counts of subgroup size, which is an important parameter in the abundance estimation process. Sometimes, though, we are still able to get good subgroup size counts during Phase 1; for example, when a subgroup is close to the trackline or when an observer watches a subgroup for multiple surfacings. However, having a phase dedicated to obtaining subgroup sizes without the constraint of staying on the trackline gives us an opportunity to increase our sample of counts and to better understand the behavior of the subgroups and, potentially, the group as a whole. Once both phases of the Pseudorca Protocol are complete, we then approach false killer whales as we would most other species, collecting identification photos, tissue samples, and even deploying satellite tags to track the movements of individuals.

If only false killer whales would follow the Pseudorca protocol! Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Charlotte Boyd (Permit #20311)

One protocol, two phases–sounds straightforward enough, right? What’s the big deal, and why all the stress? Well, first of all, when we sight false killer whales, all available hands are called to the ship’s flying bridge. In addition to the three cetacean observers on effort at any given time, the three other observers on the visual team must abruptly end their break time to serve as back-up observers, making counts of sighted subgroups during Phase 1 and helping to search for subgroups during Phase 2. The Pseudorca Protocol can go on for hours. During Phase 1, the acousticians wait in suspense for the observers to make a subgroup sighting, hoping that the visual team won’t sight another species in the meantime and ask the ship to turn, a request that must be awkwardly declined. However, Phase 2 is usually the more frustrating phase, as it often seems that once we turn around to relocate the subgroups, the whales either get playful or go quiet, behaviors that make it difficult for both teams to keep track of how many subgroups there are and how many individuals are in each. Further, call us paranoid, but we can’t help thinking that false killer whales are trying to mess with us. They always seem to show up during meals or just before sunset. They can taunt the acoustics team with their eerie whistles for miles upon miles and never show themselves at the surface. They can torment the visual team by joining and leaving subgroups or by mixing with other species. They never do the same thing twice. We are convinced that they are on to us.

Scientists aboard the NOAA Ship Oscar Elton Sette (in the background) wait anxiously while these false killer whales plot their next move. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Adam Ü (Permit #20311)

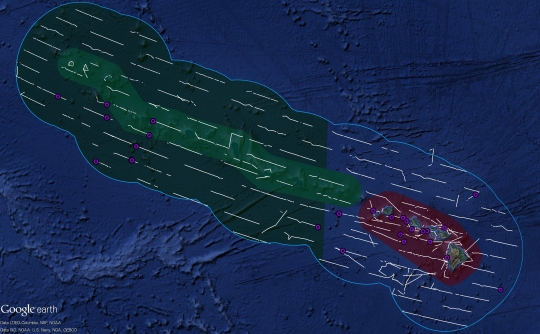

Why do we put so much effort into the data collection of this challenging species? There are three populations of false killer whales in Hawaiian waters. Obtaining accurate and precise abundance estimates is necessary for the conservation and management of these populations. The main Hawaiian Islands insular population is relatively small, numbering around 200 individuals, with a range limited to within about 50–75 nautical miles of the main Hawaiian Islands. The population is listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act because of historic declines in population size and its current small size. There is another island-associated population around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands that we know very little about.

The Hawaiʻi pelagic population is broadly distributed throughout Hawaiian waters and beyond, likely moving across broad areas following their prey. The large pelagic fish they are after are also the targets of the Hawaiʻi-based longline fisheries. False killer whales have learned to take fish from longlines, a behavior known as depredation. In the process of stealing fish from hooks, the whales sometimes end up hooked or entangled in the gear themselves. Unfortunately, these gear interactions happen enough that NOAA Fisheries had to assemble a Take Reduction Team to develop measures to reduce the bycatch of false killer whales. One of these measures defines an area that can be closed to fishing when pelagic false killer whale bycatch exceeds a threshold determined by the current abundance estimate. An imprecise abundance estimate will lower this threshold. For each of the populations, we need an accurate abundance estimate to determine if the population is healthy and sustainable. As difficult as it is, we will persevere with the Pseudorca Protocol!

This map of the Hawaiian Islands shows all of the HICEAS 2017 survey effort (white lines), with false killer whale sightings shown as violet circles. The red shading is a focus area around the main Hawaiian Islands, and the green shading is the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, with darker shading where the Monument was expanded in 2016. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

This post is the last in our "HICEAS Hilite" series. We hope you enjoyed these features of some of the cetacean species we are lucky enough to see in Hawaiian waters. HICEAS 2017 officially ended on December 1, and we have one remaining blog to post on this massive, five-month effort, so stay tuned for other final updates!