False Killer Whale

False Killer Whale

Pseudorca crassidens

Protected Status

Quick Facts

False killer whale jumping out of the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Credit: Jim Cotton

False killer whale jumping out of the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Credit: Jim Cotton

False killer whale jumping out of the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Credit: Jim Cotton

About the Species

False killer whale jumping out of the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Credit: Jim Cotton

False killer whale jumping out of the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Credit: Jim Cotton

False killer whale jumping out of the water in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Credit: Jim Cotton

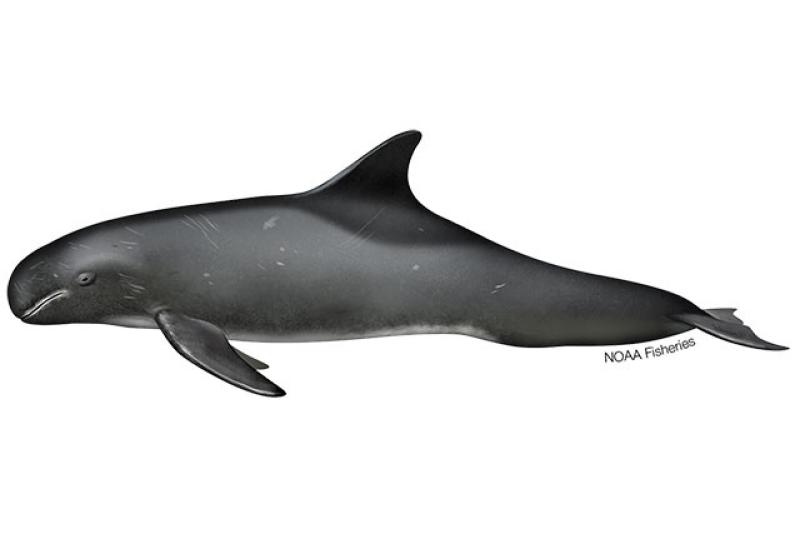

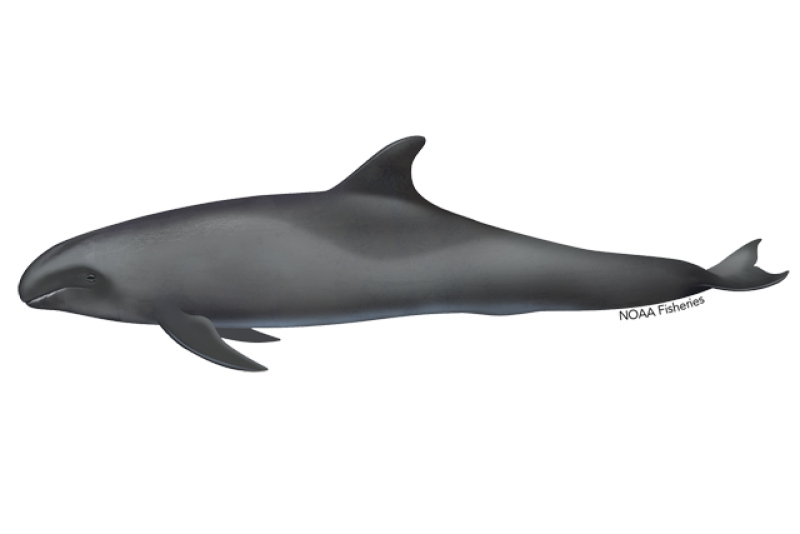

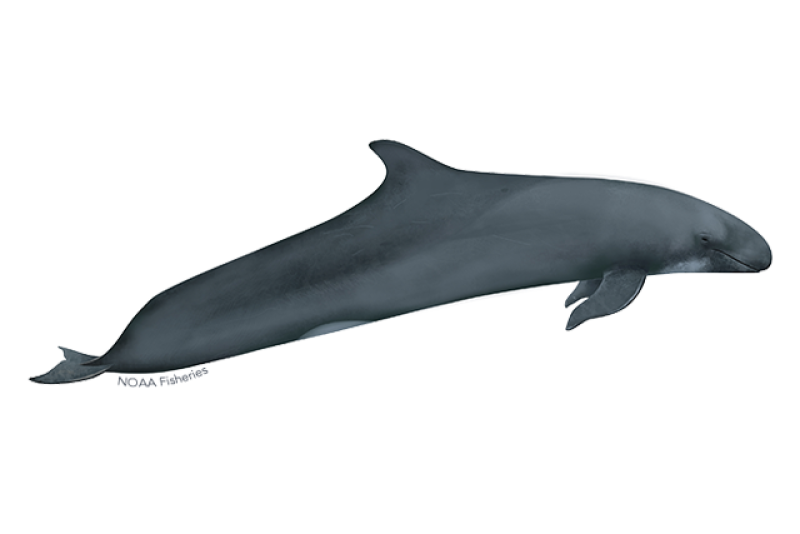

False killer whales are social animals found globally in all tropical and subtropical oceans and generally in deep offshore waters. The false killer whale’s entire body is black or dark gray, although lighter areas may occur ventrally (on its underside) between the flippers or on the sides of the head.

Fishery interactions are one of the main threats facing this species. False killer whales are known to depredate (take fish and bait off of fishing lines), which can lead to hooking and/or entanglement. This is especially a concern for false killer whales that interact with the Hawaiʻi longline fishery.

Due to its very small population size (less than 200 individuals) and population decline until at least the early 2000s, the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale distinct population segment (DPS) is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. It is the only false killer whale population protected under the ESA. This stock is also listed as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).

NOAA Fisheries is committed to conserving and protecting false killer whales. Our scientists and partners use a variety of innovative techniques to study and protect this species.

Population Status

The broad pelagic distribution of most false killer whale populations makes it difficult to estimate the global population size of this species.

The endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale distinct population segment (DPS) is estimated to number less than 200. The historical population size is unknown, though spotter planes in the late 1980s observed large aggregations of 350 to 400 whales in a single area. Aerial survey sightings since then suggest that the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale population declined at an average rate of 9 percent per year through at least the early 2000s. The current population trend is unknown.

The cause of this decline is unknown, but it’s thought to be partially due to interactions with fisheries, especially before 1990 when longline fishing was more common in the nearshore waters of Hawaiʻi. Annual variability in survey efforts within the range of the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale make it difficult to assess population trends, so it’s unknown whether the population has continued to decline, recently stabilized, or recently increased.

Sighting data collected from ship-based, line-transect surveys conducted by NOAA Fisheries within the central Pacific Ocean between 1986 to 2017 uses a model-based approach to estimate the Hawaiʻi pelagic population of false killer whales to be roughly 2,115 individuals. Their historical population size is also unknown, though interactions with longline fisheries are known to have killed or seriously injured animals in this population since at least the late 1990s. There have been only three large-scale surveys in Hawaiian waters, and changes in survey design (intended to provide more precise estimates given the social structure and behavior of false killer whales) make it difficult to determine trends in abundance for this pelagic population.

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, northern Gulf of America* (formerly Gulf of Mexico), and western North Atlantic stocks (populations) of false killer whales are not as well-studied. Current population abundance estimates for all stocks (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the northern Gulf of America, and the western North Atlantic) can be found in the latest marine mammal stock assessment reports.

Learn more about the three populations of false killer whales in Hawaiʻi

Appearance

False killer whales are large members of the dolphin family. They are dark gray, often appearing black on all but a small part of their ventral (underside) surface, which is lighter between the pectoral fins running from the throat down to the belly.

The species is large and slender, and males are slightly larger than females. They have a small conical head without a beak. The front of an adult male’s head hangs over the lower jaw to a greater extent than in females and is flattened in older males.

The pectoral fins or flippers have a distinct central hump creating an S-shape along the outer edge. The dorsal fin is located in the middle of the back and generally curves backward. In Hawaiian waters, dorsal fin shapes show a lot of variability, often caused by injury from fishery interactions.

Adult females reach lengths of 16 feet, while adult males are almost 20 feet long. In adulthood, large false killer whales can weigh up to 3,000 pounds.

Scientists can photo-identify individual whales through unique natural markings, such as scars on false killer whales’ dorsal fins or scars from cookie cutter sharks. These prominent markings to the body and dorsal fin help distinguish one whale from another.

Behavior and Diet

False killer whales are gregarious and form strong social bonds. They are often found in relatively small subgroups of a single to a few individuals that are associated with a larger aggregation that may spread over tens of kilometers. These strong social bonds between groups and dispersion into small subgroups likely help them find prey.

When they capture prey, many individuals tend to converge, and their prey items may be shared among several animals in the group. In Hawaiʻi, these larger aggregations may include 40 to 50 animals, whereas larger groups have been observed in other regions. They are known to strand in groups as well. In some regions, false killer whales are also found with other cetaceans (whales and dolphins), most notably bottlenose dolphins.

Although the range of the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale partially overlaps with the ranges of the Hawaiʻi pelagic and Northwestern Hawaiian Islands populations, genetic analyses, photo-identification, and social network analyses indicate that the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale population consists of a tight social network that is socially unconnected with the other two Hawaiʻi-based populations.

In addition to the social structure found among all three Hawaiian false killer whale populations, there is significant social structure within the main Hawaiian Islands insular population. A social network analysis indicates that this population can be broadly divided into five primary social clusters.

False killer whales are top predators that primarily hunt fish and squid. They feed both during the day and at night, hunt in dispersed subgroups, and converge when prey is captured. Prey sharing has also been observed among individuals in the group.

False killer whales can dive for up to 18 minutes and swim at high speeds to capture prey at depths of 300 to 500 meters. They often leap completely out of the water, particularly when attacking certain prey species. In Hawaiʻi, they are also known to throw fish high into the air before consuming them.

Where They Live

Habitat

False killer whales generally prefer offshore tropical to subtropical waters that are deeper than 3,300 feet.

Both main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whales and Northwestern Hawaiian Islands false killer whales maintain a more island-associated habitat, preferring to remain close to the Hawaiian Islands. This is likely due to the islands’ unique oceanographic setting, which concentrates and aggregates prey.

Distribution

False killer whales occur in tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters of all ocean basins. In the United States, they are found around Hawaiʻi, in all Pacific Remote Island Areas, the Mariana Archipelago, and in American Samoa, as well in the Gulf of America and in the warm Gulf Stream waters off the East Coast. False killer whales have been observed off the U.S. West Coast as far north as British Columbia, Canada, typically during warmer oceanographic regimes.

Learn more about the three populations of false killer whales in Hawaiʻi

World map providing approximate representation of the false killer whale range.

World map providing approximate representation of the false killer whale range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

The oldest estimated age of false killer whales (based on growth layers in teeth) is 63 years for females and 58 years for males.

Female false killer whales reach sexual maturity between the ages of 8 and 11, while males mature 8 to 10 years later. Gestation ranges from 11 to 16 months, and lactation occurs for 1.5 to 2 years. Time between births is unknown but is estimated to be around 7 years. Female false killer whales enter menopause and become less reproductively successful between 44 and 55 years old.

Threats

Fishery Interactions

Fishery interactions occur when false killer whales take (or depredate) bait and catch off fishing lines. This action can result in incidental take—unintentional hooking and/or entanglement—as well as serious injury and/or death. False killer whales in Hawaiʻi, particularly main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whales, have a high rate of dorsal fin injuries and mouthline injuries, likely caused by efforts to take bait and catch from fishing lines.

Competition with Fisheries

Prey items for false killer whales are similar to many of the same species that fisheries target. This is particularly true in Hawaiʻi, where preferred fish for both false killer whales and consumers are tuna, billfish, wahoo, and mahimahi.

Environmental Contaminants

False killer whales are long-lived, upper-trophic-level predators (that is, they’re near the top of the food chain), so they accumulate high levels of toxins from the marine environment. Exposure to toxic chemicals in the marine environment, including persistent organic pollutants (industrial chemicals and pesticides, heavy metals, etc.), can result in a number of biological effects to marine mammals, such as diseases and reproductive issues. It can also affect the quality and quantity of false killer whales’ prey. Although the United States has banned many of these chemicals, some continue to be used in other regions of the world and can be transported via atmospheric means or ocean currents.

Small Population Size

The small size of the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale population poses a unique threat to this group. Within a small, highly social population, the potential for reduced genetic diversity increases, potentially making the population more vulnerable to diseases or other environmental changes. Such environmental events may further harm the population by causing a genetic bottleneck—a reduction in the variation of the gene pool that only rebounds when the population breeds with other populations or enough random genetic mutations have accumulated over many generations. Such a small population may also suffer from a breakdown of cooperative feeding if an aggregation is not large enough to find adequate food.

Hunting

False killer whales are hunted in other parts of the world, including Indonesia, Japan, and the West Indies.

*Executive Order 14172, “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness” (Jan. 20, 2025), directs that the Gulf of Mexico be renamed the Gulf of America. Gulf of America references in this website refer to the same area as the Gulf of Mexico in the applicable regulations under 50 CFR parts 216–219, 222–226, and 600–699. The name change did not result in any changes to, and had no effect on the applicability or enforceability of, any existing regulations. This website continues to use “Gulf of Mexico” when quoting statutes, existing regulations, or previously published materials.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Delphinidae | Genus | Pseudorca | Species | crassidens |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/24/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

We are committed to conserving and protecting all populations of false killer whales. We are especially committed to protecting populations in Hawaiʻi, including recovering the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale. Our work to protect and conserve this species includes:

- Establishing a take reduction team, publishing a take reduction plan, and implementing actions to reduce bycatch of Hawaiian false killer whales in commercial longline fisheries

- Protecting habitat for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale

- Developing and implementing a recovery plan and recovery implementation strategy for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale

- Responding to stranded false killer whale

Science

We conduct various research activities on the biology, genetics, behavior, and ecology of false killer whales, with an emphasis on populations of the species in Hawaiʻi. The results of this research inform management decisions for all false killer whales and enhance recovery efforts for the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale DPS. Our work includes:

- Performing stock assessments to gather population information

- Researching false killer whale social structure

- Collaborating with scientists to track the movements and behavior of Hawaiian false killer whales.

- Identifying high-use areas of habitat in the main Hawaiian Islands

- Acoustically monitoring the Hawaiʻi-based longline fishery for interactions with false killer whales

- Conducting necropsies on stranded false killer whales

How You Can Help

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all small whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Do Not Interact with Marine Animals in the Wild

Do not harass, feed, hunt, capture, kill, pursue, approach, surround, swim with, or attempt to touch protected marine wildlife. Never entice protected marine wildlife to approach you.

Do not engage, chase, or try to get a reaction from the animal. Disturbing wildlife interrupts their ability to perform critical functions such as feeding, breeding, nursing, resting, and socializing.

If you’re on a vessel and a marine animal approaches you, put the engine in neutral and allow the animal to continue on its way.

Featured News

Behold the rounded head, dark coloration, and torpedo-like body of the false killer whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Marie Hill (Permit #25754)

Behold the rounded head, dark coloration, and torpedo-like body of the false killer whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Marie Hill (Permit #25754)

The Endangered Population of False Killer Whales in the Main Hawaiian Islands is Declining

Southern Resident killer whale swimming with calf. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Southern Resident killer whale swimming with calf. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Recommended 2024 Species Recovery Grants Projects

A false killer whale grabs a mahimahi hiding under a bucket lid, looking very much like an Avenger in the process! Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Ernesto Vazquez (Permit #25754)

A false killer whale grabs a mahimahi hiding under a bucket lid, looking very much like an Avenger in the process! Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Ernesto Vazquez (Permit #25754)

Humpback whale breaching off of Maui, Hawai’i. Credit: Ed Lyman taken under NOAA Fisheries Permit #14097

Humpback whale breaching off of Maui, Hawai’i. Credit: Ed Lyman taken under NOAA Fisheries Permit #14097

Populations

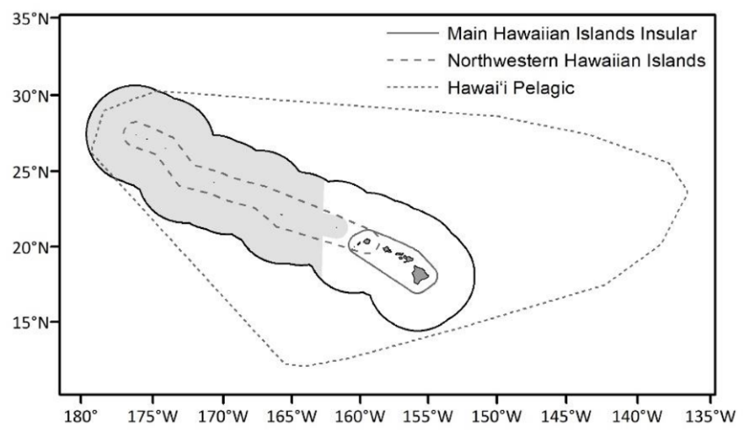

Three populations or stocks of false killer whales occur in Hawaiʻi: the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands population, the pelagic population, and the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular population.

Population boundary descriptions are complex but can be summarized as follows. The waters from shore from Kauaʻi and Niʻihau to Hawaiʻi Island out to the main Hawaiian Islands insular population boundary are considered an overlap zone between the main Hawaiian Islands insular and pelagic populations. The entirety of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands population range is an overlap zone between Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and pelagic false killer whales. All three populations overlap from shore around Kauaʻi and Niʻihau out to the main Hawaiian Islands insular population boundary.

Despite having partially overlapping ranges, the three Hawaiian false killer whale populations don’t socially interact or interbreed with one another. In fact, the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale can also be broadly divided into five social clusters, with mating occurring primarily, though not exclusively, within these clusters. This may further constrict the already limited gene flow within the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale population.

Main Hawaiian Islands Insular Population

The range of the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale is described by a modified 72-km radius (44 miles or approximately 39 nautical miles) around the main Hawaiian Islands, from Hawaiʻi Island to Niʻihau and including waters farther offshore to the southeast. The waters from shore—from the islands of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau to Hawaiʻi Island and out to the main Hawaiian Islands insular stock boundary—are considered an overlap zone between the insular and pelagic stocks. Main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whales, the population we know the most about, move widely, quickly, and regularly throughout the main Hawaiian Islands. The greatest offshore movements occur on the leeward (western) sides of the islands, where individuals tend to spread out over much larger areas, both near and far from shore. When on the windward (eastern) sides, individuals concentrate closer to shore, heavily using areas in the 1,640- to 3,937-feet depth range, particularly north of Hawaiʻi Island, Maui, and Molokaʻi. Movements between islands may occur over the course of a few days, moving from the windward to leeward side and back within a day.

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Population

The range of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands population is delineated by a 93-km (58 mile) radius around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and Kauaʻi Island, with a slight latitudinal expansion of this area at the eastern end of the range.

Hawaiʻi Pelagic Population

The Hawaiʻi pelagic population includes false killer whales inhabiting waters from around the main Hawaiian Islands and Northwestern Hawaiian Islands out to the adjacent high-seas waters.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/24/2025

Management Overview

The false killer whales Main Hawaiian Islands Insular distinct population segment (DPS) is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

The false killer whale is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

The Main Hawaiian Islands Insular stock is depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the false killer whale is listed under:

- Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

NOAA Fisheries has taken steps to reduce incidental serious injury and death of false killer whales in the Hawaiʻi-based deep-set and shallow-set longline commercial fisheries. NOAA Fisheries also designated critical habitat for the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale in 2018. A Final Recovery Plan and associated Recovery Implementation Strategy for the Main Hawaiian Islands Insular False Killer Whale were published on November 3, 2021.

A 5-year review that determined the "endangered" listing status is still appropriate was published in April 2022.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries is required to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. We are committed to the protection and recovery of the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale, with the ultimate goal of helping this distinct population segment recover from its very low population size. This would allow the population to be reclassified from endangered to threatened and ultimately be removed from the list of threatened and endangered species.

Recovery Outline

The ESA mandates that NOAA Fisheries develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of ESA-listed species under its jurisdiction. In September 2016, we developed a recovery outline to systematically and cohesively guide recovery actions for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale until we completed a recovery plan.

Recovery Planning Workshop

On October 25 to 28, 2016, we held a recovery planning workshop for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale. The purpose of the workshop was to review and update the original threats analysis from the 2012 final listing rule and the 2010 Status Review Report, as well as identify potential recovery criteria and actions to address the threats to the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale. Participants included federal and state agencies, scientific experts, commercial and recreational fishermen, conservation partners, and nongovernmental organizations.

- Recovery Planning Workshop Agenda (PDF, 7 pages)

- Main Hawaiian Islands Insular False Killer Whale Recovery Outline

- Recovery Planning Workshop Summary (PDF, 27 pages)

Recovery Plan Preparation

In addition to using recovery planning guidance, we based this plan on a recovery planning approach developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and recently adopted by NOAA Fisheries as an optional approach to traditional recovery plans. In this approach, recovery planning components are divided into three separate documents. The three-part strategy, briefly described below, will make recovery planning more efficient and effective. It will also create a more dynamic and flexible plan, presented in three independent parts: a recovery status review, a recovery plan, and a recovery implementation strategy.

Recovery Status Review

Using the 2010 Status Review Report for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale as a foundation, we developed an up-to-date Recovery Status Review for the species. A Recovery Status Review is a stand-alone document that provides all the detailed information on the species' biology, ecology, status and threats, and conservation efforts to date. This document, which was published in October 2020 and updated in August 2021, will be updated as necessary with new information and used for various purposes, including 5-year reviews, Section 7 consultations, and section 10 conservation plans. Traditionally, this information was included in the background of a recovery plan and became outdated quickly. As a stand-alone living document, information can be kept more relevant.

Recovery Plan

We published a Draft Recovery Plan for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale in October 2020 (85 FR 65791) and a Final Recovery Plan in November 2021 (86 FR 60615). The three statutory elements required in a recovery plan are contained in this second stand-alone document:

- Objective, measurable recovery criteria

- A description of site-specific management actions necessary to conserve the species

- Estimates of the time and costs required to achieve the plan's goals

In this Final Recovery Plan, actions are described at a higher-level and are more strategic. In addition, a brief introduction to the plan describes its vision (what the recovered species looks like) and strategy (the rationale for, and how we plan to get to a recovered state). This introduction provides the trail of logic for recovery and references the Recovery Status Review.

Additionally, the Final Recovery Plan recommends the following recovery objectives for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale:

- Ensure population abundance, trend, and number of social groups meet or exceed target levels

- Address threats from fisheries including incidental take and competition with fisheries for prey

- Address threats from environmental contaminants and biotoxins

- Address threats from anthropogenic noise

- Better understand the effects of climate change and manage accordingly

- Ensure that regulatory mechanisms, including state and federal management and post-delisting monitoring, are in place

- Ensure that secondary threats and synergies among threats are not limiting recovery of the population

Learn more about the recovery of species under the Endangered Species Act

Recovery Implementation Strategy

Lastly, we published a Draft Recovery Implementation Strategy for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale in October 2020 (85 FR 65791) with an updated version of the Recovery Implementation Strategy published in November 2021 (86 FR 60615). This third document is a flexible, operational document that is intended to assist NOAA Fisheries and other stakeholders in planning and implementing activities to carry out the recovery actions in the Recovery Plan. The stepped-down recovery activities identified in the Recovery Implementation Strategy can be adapted or modified as the science evolves. As long as the activities don't meaningfully deviate from the recovery actions, objectives, and criteria, they do not need to go out for public comment with each change. If/when the science indicates that meaningful changes to the recovery actions, objectives, and criteria are necessary, the recovery plan will be revised and go out for public comment. This affords us the ability to modify these activities in real time to reflect changes in the information available as well as progress towards recovery.

All documents used to inform the recovery of the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale including the Recovery Status Review, Recovery Plan, and Recovery Implementation Strategy underwent peer review. Public comments on both the Draft Recovery Plan and Draft Recovery Implementation Strategy were accepted through December 15, 2020, and were considered before finalizing the recovery plan and recovery implementation strategy in November 2021.

Learn more about the recovery of species under the Endangered Species Act

Critical Habitat Designation

On July 24, 2018, NOAA Fisheries published a final rule to designate critical habitat under the ESA for main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whales in waters from 45 meters to 3,200 meters (49 to 3,500 yards) in depth surrounding the main Hawaiian Islands (from Niihau to Hawaii Island). This designation does not include most bays, harbors, or coastal in-water structures.

The physical and biological features essential to the conservation of the species include:

- Adequate space for movement and use within shelf and slope habitat

- Prey species of sufficient quantity, quality, and availability to support individual growth, reproduction, and development, as well as overall population growth

- Waters free of pollutants of a type and amount harmful to the species

- Sound levels that would not significantly impair false killer whales’ use or occupancy of their habitat

5-Year Status Review

On October 16, 2020, we announced our intention to conduct a 5-year review for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale distinct population segment to determine if it should still be listed as endangered under the ESA (85 FR 65791). The resulting public information and comments were used to inform the 5-year review, as appropriate.

In April 2022, we published a 5-year review that determined that the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale distinct population segment should remain listed as endangered. We will continue to reexamine the status once every five years to address new information available on this species. Our ultimate goal is to recover the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale distinct population segment to the point where the species no longer needs protection under the ESA.

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Interactions with Fishing Gear

Bycatch in fishing gear is a leading cause of false killer whale deaths and injuries. To reduce deaths and serious injuries of false killer whales from Hawai‘i-based deep-set and shallow-set longline fisheries, NOAA Fisheries established a take reduction team. We then published a final take reduction plan and final rule to implement the plan in 2012, based on the take reduction team's recommendations. The final rule includes gear requirements (“weak” circle hooks and strong branch lines) in the deep-set longline fishery, longline fishing closure areas, training and certification for vessel owners and captains in marine mammal handling and release, captains’ supervision of marine mammal handling and release, and posting of placards on longline vessels to aid in species identification and handling and release techniques. We also develop research priorities to support the plan’s implementation and inform development of potential future amendments, and we monitor its progress toward achieving MMPA goals.

Learn more about the False Killer Whale Take Reduction Plan

False killer whales are classified as data deficient on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. NOAA Fisheries funds several research studies on life history and stock structure of false killer whales in Hawaiʻi.

Partnering with the State of Hawaiʻi

NOAA Fisheries partners with the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Department of Aquatic Resources to undertake cooperative conservation and long-term management of the endangered main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale. Our objectives include:

- Conducting field work to address false killer whales’ spatial and temporal habitat use

- Analyzing overlap between false killer whales and Hawaiʻi state fisheries

- Investigating strandings

- Providing targeted outreach to specific fishers, boaters, and tour operators to mitigate or reduce interactions with false killer whales; improve species identification to complement research; and increase public reporting of strandings

These efforts are funded in part via an ESA section 6 cooperative agreement grant.

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

False killer whales have never been part of a declared unusual mortality event. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Regulatory History

False Killer Whale Populations Managed Under the MMPA

All false killer whales that reside in the United States are protected under the MMPA. Although there are three populations or stocks of false killer whales in Hawaiian waters, only the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale is listed as depleted (i.e., they have fallen below their optimum sustainable population level). Under the MMPA, the False Killer Whale Take Reduction Plan addresses the threat of incidental serious injury and death of false killer whales in the Hawai'i-based deep-set and shallow-set longline fisheries.

False Killer Whale Populations Managed Under the ESA

The main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale is the only false killer whale population protected under the ESA.

In 2009, NOAA Fisheries received a petition (PDF, 29 pages) to list the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale as an endangered species and designate critical habitat under the ESA.

NOAA Fisheries reviewed the petition and determined that a status review for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale should be conducted.

On November 17, 2010, NOAA Fisheries completed a status review of the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale and proposed to list it as an endangered DPS under the ESA. Read the ESA status review report.

On September 18, 2012, NOAA Fisheries released a report—Reevaluation of the DPS Designation for Main Hawaiian Islands Insular False Killer Whales—that further supported the final determination of whether the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale was a DPS that qualified for listing as endangered under the ESA.

On November 28, 2012, NOAA Fisheries published a final rule listing the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale as an endangered DPS under the ESA.

In July 2018, NOAA Fisheries published a final rule to designate critical habitat under the ESA for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale in waters from 45 meters to 3,200 meters in depth surrounding the main Hawaiian Islands (from Ni‘ihau to Hawai‘i Island).

In October 2020, NOAA Fisheries published a Draft Recovery Plan and Draft Recovery Implementation Strategy to identify actions that will protect the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale.

In November 2021, NOAA Fisheries published a Final Recovery Plan and Recovery Implementation Strategy to identify actions that will protect the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale.

Key Actions and Documents

Incidental Take Authorization: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory's Marine Geophysical Survey off Western Mexico in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean

Military Readiness Activities in the Hawaii-California Training and Testing (HCTT) Study Area (2025-2032)

Incidental Take Authorization: Scripps Institution of Oceanography's Marine Geophysical Survey in the Nauru Basin of Greater Micronesia in the NW

Incidental Take Authorization: Military Readiness Activities in the Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing (AFTT) Study Area (2025-2032)

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/24/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research on the biology, behavior, ecology, and genetics of false killer whales, with a special focus on Hawaiian false killer whales. We use the results of this research to inform management decisions, further direct scientific research, and enhance conservation and recovery efforts for the species.

In collaboration with fishermen of the Hawaiʻi longline deep-set fishery, we conduct research to investigate interactions between false killer whales and fishing gear. We deploy small, autonomous acoustic recorders on longline fishing gear to acoustically monitor fishing sets for the presence of false killer whales. We compare the acoustic presence of false killer whales to fishing activity and depredation rates to assess vessel and gear sounds and false killer whale occurrence and behavior around gear, as well as to identify potential acoustic cues.

Visual Observations

We collect observations of whales and dolphins following line-transect protocols. Observers continuously search for animals using 25x150 "big-eye" binoculars to scan 180° forward of the ship. When they spot whales or dolphins, the visual team identifies the species and each observer independently estimates the number of animals in the group.

Passive Acoustic Surveys

Sound travels much farther in water than light, and cetaceans commonly use sound rather than vision to communicate with each other and find food. Just as cetaceans listen for each other and for their prey, we can listen to their sounds to locate groups of whales and dolphins.

Unmanned Aircraft Systems

Target species for Unmanned Aircraft Systems operations include false killer whales, short-finned pilot whales, sperm whales, and Bryde’s whales. We may also conduct flights during sightings of rare and high-profile species, such as killer whales, blue whales, and North Pacific right whales, to maximize the information gained from such unique opportunities.

Surveying with Drifting Autonomous Spar Buoy Recorders

We’ve broadly used autonomous (no human intervention needed) stationary acoustic recorders to understand the distribution and seasonality of cetaceans throughout the world’s oceans. Our scientists maintain a network of seafloor-anchored passive acoustic listening stations to listen for cetaceans and understand ocean noise.

Identifying "Mystery Whales" Using Environmental DNA

The name eDNA derives from the collection method—essentially, we are detecting the DNA of an individual as it passes through the environment and sheds small bits of tissue, such as sloughed skin.

Ocean Noise Reference Stations

To monitor ocean noise, NOAA has deployed acoustic monitoring stations throughout U.S. waters that together make up the Ocean Noise Reference Station Network. One of these stations is located approximately 100 miles north of Oʻahu.

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/24/2025

Documents

Accounting for Sampling Bias Reveals a Decline in Abundance of Endangered False Killer Whales in the Main Hawaiian Islands

Peer-reviewed journal article in Endangered Species Research about false killer whale population…

Developing a Management Area for Hawaiʻi Pelagic False Killer Whales

Defining a new management area that accounts for what is known about the distribution of Hawaiʻi…

Main Hawaiian Islands Insular False Killer Whale Distinct Population Segment 5-Year Review

Endangered Species Act 5-year Review for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer whale…

Final Recovery Plan and Recovery Implementation Strategy for the Main Hawaiian Islands Insular False Killer Whale Distinct Population Segment

Final Recovery Plan and Recovery Implementation Strategy for the Main Hawaiian Islands Insular…

Data & Maps

False Killer Whale Stock Boundary Maps

Range maps for populations (stocks) of false killer whales in Hawaiian waters.

Main Hawaiian Islands Insular False Killer Whale Critical Habitat Map and GIS Data

Map and GIS data representing critical habitat for the main Hawaiian Islands insular false killer…

Research

False Killer Whales and Fisheries in Hawaiian Waters: Evidence From Mouthline and Dorsal Fin Injuries Reveal Ongoing and Repeated Interactions

Results suggest that efforts to reduce bycatch and begin monitoring of fisheries that overlap the…

Identifying Social Clusters of Endangered Main Hawaiian Islands False Killer Whales

In this study, we used photo-identification data over a 23 year period to reassess the number and…

Passive Acoustic Research at the Southeast Fisheries Science Center

The Passive Acoustic Ecology Program conducts research projects that use passive acoustics to assess populations and improve our understanding of cetaceans in the Gulf of America and U.S. waters of the Western Atlantic.

Tracking Time Differences of Arrivals of Multiple Sound Sources in the Presence of Clutter and Missed Detections

This study proposes a multi-target tracking method to automate TDOA tracking demonstrated on false…

Outreach & Education

NOAA Marine Wildlife Hotline Poster – Pacific Islands

Poster featuring the NOAA Fisheries hotline (888-256-9840) to report monk seal sightings, injured…

Viewing Marine Wildlife in Hawai'i Rack Card

A guide for viewing protected sea turtles, monk seals, dolphins, and whales responsibly in Hawai'i.

Valentine Cards to “Share the Love” for Marine Animals in the Pacific Islands Region

Eight valentine cards with drawings to color, fun facts, and viewing distances for humpback whales,…

Marine Mammal Strandings FAQ Rack Card for the Pacific Islands Region

Educational rack card designed to provide key information for the public in the event of a marine…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/24/2025