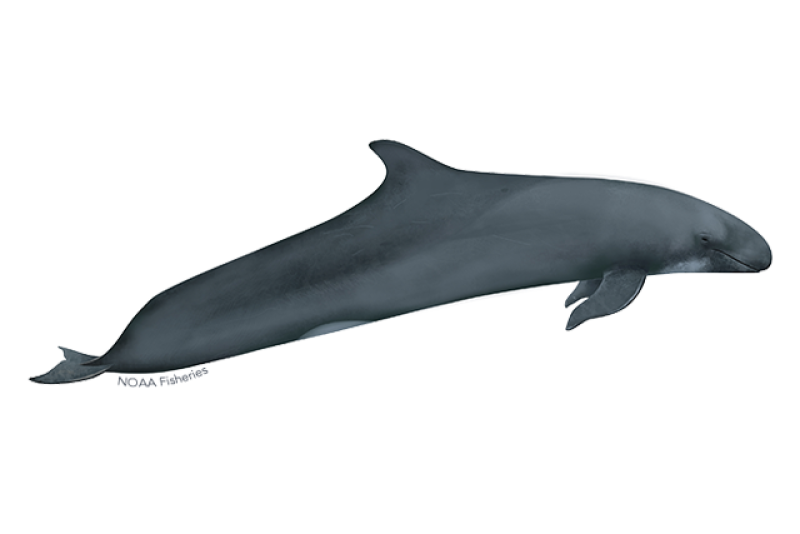

Risso’s Dolphin

Grampus griseus

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Risso's dolphin observed during the 2010 Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/J. Cotton

Risso's dolphin observed during the 2010 Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/J. Cotton

Risso's dolphin observed during the 2010 Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/J. Cotton

About the Species

Risso's dolphin observed during the 2010 Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/J. Cotton

Risso's dolphin observed during the 2010 Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/J. Cotton

Risso's dolphin observed during the 2010 Hawaiian Islands Cetacean and Ecosystem Assessment Survey. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/J. Cotton

Risso's dolphins, sometimes called gray dolphins, are found in the temperate and tropical zones of all the world’s oceans. These cetaceans generally prefer deeper offshore waters, especially near the continental shelf edge and slope, where they can dive to at least 1,000 feet and hold their breath for 30 minutes. They are also very active on the ocean surface.

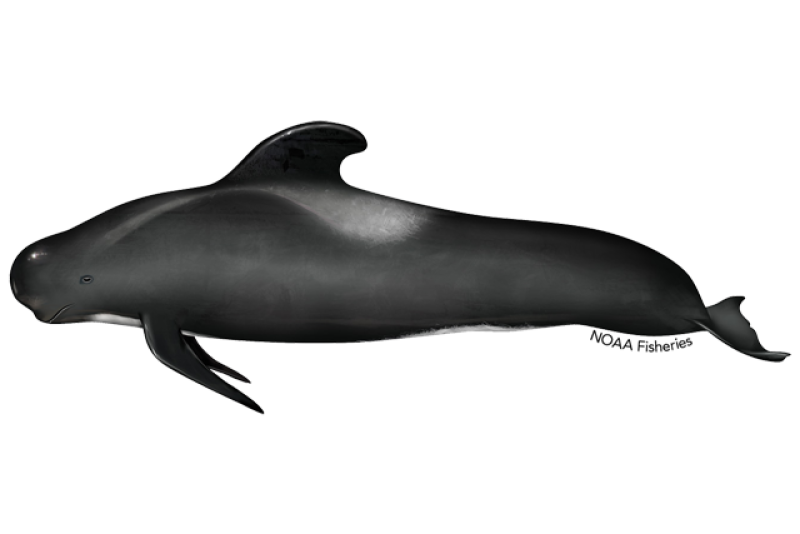

Risso's dolphins are typically found in groups of between 10 and 30 animals, though they have been reported as solitary individuals, in pairs, or in loose aggregations in the hundreds or thousands. Occasionally, this species associates with other dolphins and whales. They are sometimes considered part of a subfamily referred to as “blackfish,” which also includes false killer whales, pygmy killer whales, melon-headed whales, long-finned pilot whales, and short-finned pilot whales.

Risso’s dolphins in the United States are not endangered or threatened. Like all marine mammals, they are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). NOAA Fisheries and its partners are working to conserve Risso’s dolphins and further our understanding of this species through research and conservation activities.

Population Status

NOAA Fisheries estimates population size for each stock of Risso’s dolphin in its stock assessment reports.

Appearance

Risso's dolphins have a robust body with a narrow tailstock. These medium-sized cetaceans can reach lengths of approximately 8.5 to 13 feet and weigh 660 to 1,100 pounds. Males and females are usually about the same size. They have a bulbous head with a vertical crease and an indistinguishable rostrum. They have a tall, curved, sickle-shaped dorsal fin located mid-way down their back.

Calves have a dark cape and saddle, with little or no scarring on their body. As Risso's dolphins age, their coloration lightens from black, dark gray, or brown to pale gray or almost white. Adult bodies are usually heavily scarred, with scratches caused from teeth raking between dolphins, as well as circular markings from prey (e.g., squid), cookie-cutter sharks, and lampreys. Mature adults swimming just under the water's surface usually appear white.

Risso’s dolphins have two to seven pairs of peg-like teeth in the front of their lower jaw to capture prey and usually none in their upper jaw. This low number of teeth is unusual when compared with other cetaceans.

Behavior and Diet

Risso's dolphins are typically found in groups that average between 10 and 30 animals, but they have been reported as solitary individuals, in pairs, or in loose aggregations of hundreds and thousands. Occasionally, this species associates with other dolphins and whales, such as bottlenose dolphins, gray whales, northern right whale dolphins, and Pacific white-sided dolphins.

When at the surface, they have a small inconspicuous blow if backlit (which is more distinct after long dives), and their head partially emerges at a 45° angle. Before diving, they usually take 10 to 12 breaths at 15- to 20-second intervals and will often display their tails (known as flukes). Risso’s dolphins are very active on the surface, often leaping out of the water, slapping their pectoral flippers or tails on the water's surface, and raising their heads vertically out of the water (known as spyhopping). They occasionally 'porpoise'—or move in and out of the water in a series of high-speed leaps—most often when being pursued or hunted by predators.

Risso's dolphins can dive to at least 1,000 feet and hold their breath for 30 minutes, but they usually make shorter dives of just a few minutes. They feed on fish (e.g., anchovies), krill, and cephalopods (e.g., squid, octopus, and cuttlefish) mainly at night, when their prey is closer to the surface. Most of their diet consists of squid, and they have been known to move into continental shelf waters when following their preferred prey.

Where They Live

Risso's dolphins have a cosmopolitan distribution, meaning they can be found worldwide in temperate, subtropical, and tropical oceans and seas from latitudes 64° North to 46° South. Their preferred habitats appear to be mid-temperate waters of the continental shelf and slope between 30° and 45° latitude. They prefer areas of deeper waters (3,300 feet) with steep bottom topography, but they are known to inhabit shallow coastal areas as well.

In the Northern Hemisphere, their range includes the Gulf of Alaska, Gulf of America, Gulf of Mexico, Northwest Atlantic from Florida to Newfoundland, Azores, Norway, Japan, Russia, and the Red Sea. In addition, they are known to inhabit the Mediterranean Sea, are rare in the Black Sea, and do not appear to inhabit the Persian Gulf and some other very shallow, enclosed bodies of water. In the Southern Hemisphere, their range includes Argentina, Australia, Chile, South Africa, and New Zealand.

Little is known of their migration patterns or movements, but Risso’s dolphins may be affected by movements of spawning squid and oceanographic conditions.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Risso’s dolphins have an estimated lifespan of at least 35 years. Individuals become sexually mature when they reach a length of about 8.5 to 9 feet. Breeding and calving may occur year-round and the gestation period lasts approximately 13 to 14 months. The peak of the breeding and calving season may vary geographically (especially in the North Pacific), with most animal births occurring from summer to fall in Japanese waters and from fall to winter in California waters. Newborn calves are usually 3.5 to 5.5 feet in length and weigh about 45 pounds.

Threats

Entanglement

One of the main threats to Risso’s dolphins is becoming entangled or captured in commercial fishing gear such as gillnets, longlines, and trawls.

Hunting

Risso’s dolphins are directly hunted for meat and oil in Indonesia, Japan, the Caribbean (the Lesser Antilles), Sri Lanka, and the Solomon Islands.

Ocean Noise

Underwater noise threatens Risso's dolphin populations, interrupting their normal behavior and driving them away from areas important to their survival. Increasing evidence suggests that exposure to intense underwater sound in some settings may cause this species to strand and ultimately die.

Contaminants

Contaminants enter ocean waters from many sources, including oil and gas development, wastewater discharges, urban runoff, and other industrial processes. Once in the environment, these contaminants move up the food chain and accumulate in predators at the top, such as Risso’s dolphins. Because of their long lifespan and blubber stores, Risso’s dolphins accumulate contaminants including trace metals and organochlorines like PCBs and DDTs in their bodies, threatening their immune and reproductive systems. Coastal populations generally are more susceptible.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Delphinidae | Genus | Grampus | Species | griseus |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/06/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

All Risso’s dolphins are protected under the MMPA. Our work protects Risso’s dolphins by:

- Reducing interactions with commercial fishing gear

- Issuing take reduction plans and implementing regulations to reduce serious injuries and mortalities

- Minimizing the effects of vessel disturbance, noise, and other types of human impacts

Science

Our research projects have helped us better understand Risso’s dolphins and the challenges they face. Our work includes:

- Stock assessments

- Aerial surveys

- Shipboard surveys

How You Can Help

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all dolphins and porpoises from a safe distance of at least 50 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Do Not Interact with Marine Animals in the Wild

Do not harass, feed, hunt, capture, kill, pursue, approach, surround, swim with, or attempt to touch protected marine wildlife. Never entice protected marine wildlife to approach you.

Do not engage, chase, or try to get a reaction from the animal. Disturbing wildlife interrupts their ability to perform critical functions such as feeding, breeding, nursing, resting, and socializing.

If you’re on a vessel and a marine animal approaches you, put the engine in neutral and allow the animal to continue on its way.

Featured News

Common dolphins. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Michelle Klein

Common dolphins. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Michelle Klein

Celebrating 15 Years of Surveying Protected Species in the Northwest Atlantic

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Protecting Species While Planning for Offshore Wind Development in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico

Pilot whales surface near the NOAA Ship Gordon Gunter. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Melody Baran (Permit # 14450)

Pilot whales surface near the NOAA Ship Gordon Gunter. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Melody Baran (Permit # 14450)

Deceased dolphin as a result of domoic acid poisoning. Credit: Channel Islands Marine & Wildlife Institute

Deceased dolphin as a result of domoic acid poisoning. Credit: Channel Islands Marine & Wildlife Institute

Toxic Algal Bloom Suspected in Dolphin and Sea Lion Deaths in Southern California

Management Overview

The Risso’s dolphin is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the Risso’s dolphin is listed under:

- Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Risso’s dolphins are caught as bycatch in fishing gear, leading to serious injuries and death. In 2005, NOAA Fisheries convened the Atlantic Pelagic Longline Take Reduction Team to address bycatch of Risso's dolphins in the mid-Atlantic region of the Atlantic pelagic longline fishery. The team submitted its recommendations for reducing bycatch to NOAA in 2006. NOAA Fisheries published a proposed rule to implement the Pelagic Longline Take Reduction Plan on June 24, 2008, and NOAA Fisheries published a final rule (74 FR 23349) on May 19, 2009.

Learn more about bycatch and fisheries interactions

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all dolphins and porpoises. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Risso’s dolphins have been part of a declared unusual mortality event in the past. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Get information on active and past UMEs

Get an overview of marine mammal UMEs

Addressing Ocean Noise

Underwater noise threatens whale and dolphin populations, interrupting their normal behavior and driving them away from areas important to their survival. Increasing evidence suggests that exposure to intense underwater sound in some settings may cause Risso’s some dolphins to strand and ultimately die. NOAA Fisheries is investigating all aspects of acoustic communication and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on dolphin behavior and hearing. In 2016, we issued marine mammal acoustic technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic (human-caused) sound on marine mammal hearing.

Regulatory History

Risso’s dolphins are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).

In 1999, the United States signed on as a Party to the Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program. In addition to other requirements, the AIDCP mandates the establishment of an international tuna tracking program for tuna caught in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The program helps minimize dolphin deaths during fishing for tuna destined for canning.

The International Dolphin Conservation Program Act (PDF, 19 pages) amended the MMPA to make the objectives and requirements of the AIDCP legally effective in the United States.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/06/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of Risso’s dolphins. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions for this species.

Stock Assessments

Determining the size of Risso’s dolphin populations helps resource managers determine the success of NOAA Fisheries’ conservation measures. Our scientists collect and present these data in annual stock assessment reports.

Shipboard Studies

NOAA Fisheries conducts research cruises to collect information on dolphin stocks, such as habit preferences and feeding ecology. For example, NOAA Fisheries has used oceanic research vessels to perform surveys of Risso’s dolphin movements and distribution. Information from this research can be used in management actions to protect these animals.

Aerial Surveys

Scientists have used small aircraft to observe and record Risso’s dolphin numbers and distribution. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center conducts population estimates every 2 to 5 years to monitor the health, status, and trends of the population in its region. By comparing numbers collected over multiple years, scientists can spot trends, such as whether the population is increasing, decreasing, or remaining stable.

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/06/2025

Documents

Injury Determinations for Marine Mammals Observed Interacting With Hawaii and American Samoa Longline Fisheries During 2015–2016

Marine mammal interactions (i.e., hookings and entanglements) with the Hawaii and American Samoa…

Research

Geographic variation in Risso's dolphin echolocation click spectra

This study investigates using clicks for species and population identification by characterizing…

California Current Marine Mammal Assessment Program

We assess the population status of marine mammals in the California Current.

Outreach & Education

Dolphin Friendly Fishing Tips Sign

This sign is often posted near boat ramps, piers, docks, marinas, and waterfront parks.

Protect Wild Dolphins Sign

This sign is often posted near boat ramps, piers, docks, marinas, and waterfront parks.

Don't Feed Wild Dolphin Sign

This sign is often posted near boat ramps, piers, docks, marinas, and waterfront parks.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/06/2025