Long-Finned Pilot Whale

Globicephala melas

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Long-finned pilot whale. Credit: Howard Goldstein, courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography/ UCSD and R/V Roger Revelle

Long-finned pilot whale. Credit: Howard Goldstein, courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography/ UCSD and R/V Roger Revelle

Long-finned pilot whale. Credit: Howard Goldstein, courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography/ UCSD and R/V Roger Revelle

About the Species

Long-finned pilot whale. Credit: Howard Goldstein, courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography/ UCSD and R/V Roger Revelle

Long-finned pilot whale. Credit: Howard Goldstein, courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography/ UCSD and R/V Roger Revelle

Long-finned pilot whale. Credit: Howard Goldstein, courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography/ UCSD and R/V Roger Revelle

Long-finned pilot whales are very social, living in large schools of hundreds of animals separated into close-knit pods of 10 to 20 individuals. This structure made them easy targets for whaling in the 19th and 20th centuries. Whalers would drive and herd pilot whales together into tight groups to harpoon them, hunting them for their meat, oil, and blubber.

Long-finned pilot whales are one of two species of pilot whale, along with short-finned pilot whales. In the field and at sea, it is very difficult to distinguish the two species, which differ only slightly in physical size, features, coloration, and pattern.

Population Status

Long-finned pilot whales, like all marine mammals, are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Review the most recent stock assessment report with population estimates

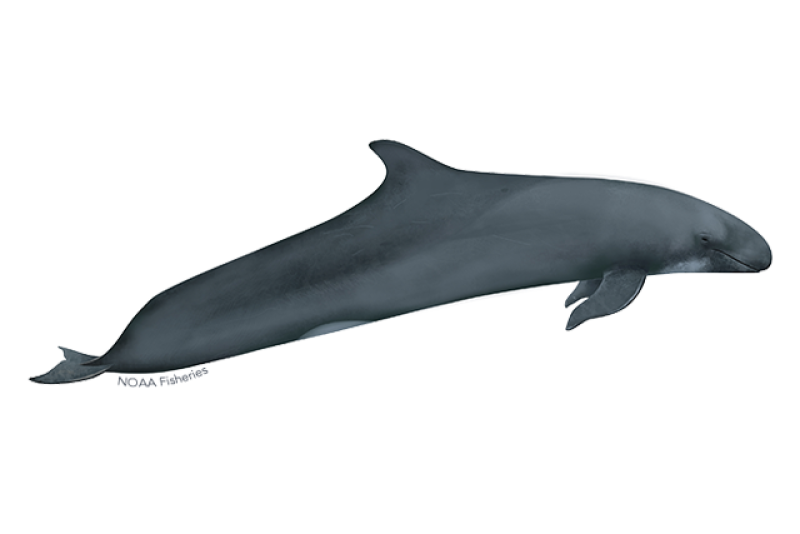

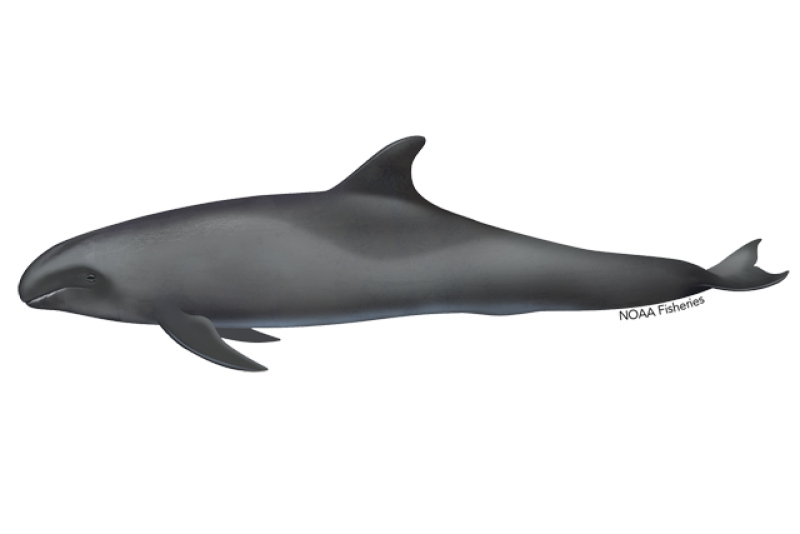

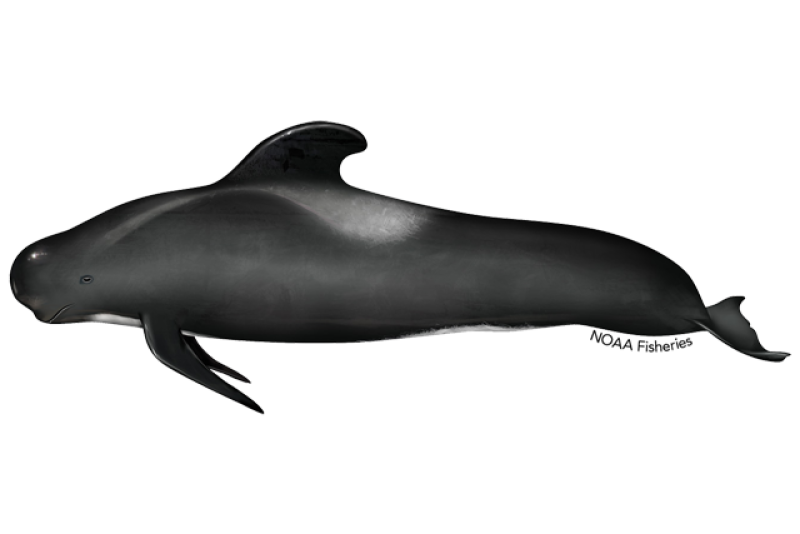

Appearance

Long-finned pilot whales are wide-ranging, medium-sized animals that have a stocky, sturdy body. They have a large bulbous or squarish forehead, known as a melon, that varies with age and sex. In some animals, the melon can develop a prominent crease. Long-finned pilot whales have 16 to 26 peg-like teeth in each jaw, which may be an evolutionary adaptation to consuming large amounts of soft squid. Their thick dorsal fin is located about a third of the body length behind the head. As they mature, their dorsal fin becomes broader and rounder.

This species gets its common name from the pair of long, tapered, sickle-shaped flippers on either side of its body. Long-finned pilot whales are dark black in color, but can sometimes appear dark gray or brownish. They have pale grayish or whitish marks, such as a diagonal eye-stripe, or a blaze, that extends from behind the eye and up towards the dorsal fin. They also have a large saddle behind the dorsal fin and an anchor-shaped patch that starts at the throat and extends down their underside.

Behavior and Diet

Long-finned pilot whales are commonly seen in tight, social pods and sub-groups (usually containing more females than males) of 10 to 20 individuals but have been reported in loose groupings of several hundred or even up to a thousand animals. Studies have shown that these established pods are maternally based. The strong social structure of these animals has been suggested by mass strandings on beaches. Long-finned pilot whales are known to associate with a variety of other dolphin and whale species and sometimes even sharks.

At the surface, these whales will often display various active behaviors such as raising their heads above the surface or lifting their flukes out of the water and splashing them down against the surface. They are also regularly seen resting or logging at the surface in a chorus-line or stacked formation and sometimes approach vessels moving at slow speeds. This species has a small, strong, low, bushy blow that is often visible.

Long-finned pilot whales can dive to depths of about 2,000 feet for 10 to 16 minutes to feed on fish (e.g., cod, dogfish, hake, herring, mackerel and turbot), cephalopods (e.g., squid and octopus) and crustaceans (e.g., shrimp). Most feeding occurs at night in deep water between depths of 650 and 1,650 feet. Like other members of the delphinid family, long-finned pilot whales echolocate when foraging for prey.

Where They Live

Long-finned pilot whales prefer deep temperate to subpolar oceanic waters, but they have been known to occur in coastal waters in some areas. Larger groupings of animals have been documented on the continental edge and slope, depending on the season. This species has been described as "anti-tropical." Three distinct populations or subspecies of long-finned pilot whales are recognized:

- Southern Hemisphere

- North Atlantic

- An unnamed extinct form in the western North Pacific

In the Southern Hemisphere, their range extends from 19° S to 60° S, but they have been regularly sighted in the Antarctic Convergence Zone (47° to 62° south) and in the Central and South Pacific as far south as 68° south. They have been documented near the Antarctic sea ice and associated with the colder Benguela and Humboldt Currents, which may extend their normal range, as well as the Falklands. The southern subspecies range includes Cape Province, South Africa; Chile; southern Australia; New Zealand; and Sao Paulo, Brazil. In the Northern Hemisphere, their range includes the U.S. east coast, Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Azores, Madeira, North Africa, western Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Greenland and the Barents Sea. In the winter and spring, they are more likely to occur in offshore oceanic waters or on the continental slope. In the summer and autumn, long-finned pilot whales generally follow their favorite foods farther inshore and on to the continental shelf.

World map providing approximate representation of the long-finned pilot whale's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the long-finned pilot whale's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Males become sexually mature at 12 to 13 years and females at 8 years. Breeding and mating usually takes place between the months of April and September in the Western North Atlantic and between October and April in the Southern Hemisphere. Every 3 to 6 years a single calf is born after a gestation period of 12 to 16 months. This is one of the longest known birth intervals of all cetaceans. At birth, calves measure about 5 to 6.5 feet and weigh about 165 pounds. After 18 to 44 months, the calf stops nursing and is weaned by the cow. Older and/or non reproductive females help care for calves in the social group. The lifespan of long-finned pilot whales is 35 to 45 years for males and at least 60 years for females.

Threats

Entanglement

Long-finned pilot whales can become entangled or hooked in fishing gear, either swimming off with the gear attached or becoming captured in the gear. They can become entangled in many different gear types, including gillnets, longlines, and trawls. Once entangled, whales may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances, ultimately resulting in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury, which may lead to reduced reproductive success and death.

Whaling

Historically, whalers benefited from pilot whales’ strong social structure and would drive and herd them together into tight groups during hunts. In the 19th and 20th centuries, American sperm whalers in the North Atlantic harpooned them, while a drive fishery in Newfoundland targeted them for meat, blubber, and oil. Drive fisheries for this species also historically occurred in the Falkland Islands, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Scotland (Orkney Islands and Hebrides Islands), and the United States (Cape Cod, Massachusetts). Currently, shore-based hunters in the Faroe Islands (Denmark) continue to directly target long-finned pilot whales.

Disease

Morbillivirus has affected pilot whales in the North Atlantic and certain strains of the virus may be native to specific areas. The historical prevalence of morbillivirus in the blood of these whales suggests that they may have increased contact with the virus. This increased exposure means that enough of the population is immune to the virus to prevent serious outbreaks of infectious disease from occurring in areas of the western Atlantic.

Contaminants

Contaminants enter ocean waters and sediments from many sources, such as wastewater treatment plants, sewer outfalls, and pesticide application. Once in the environment, these substances move up the food chain and accumulate in species such as long-finned pilot whales. Pollutants and various contaminants in the marine environment have been found in their blubber. These pollutants can harm their immune and reproductive systems.

Despite modern pollution controls, chemical contamination through the food chain continues to threaten long-finned pilot whales. These controls have reduced, but not eliminated, many contaminants in the environment. Additionally, some of these contaminants persist in the marine environment for decades and continue to threaten marine life.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Delphinidae | Genus | Globicephala | Species | melas |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/14/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

NOAA Fisheries is committed to protecting long-finned pilot whales. Targeted management actions taken to secure protections for these whales include:

- Reducing interactions with fishing gear

- Minimizing the effects of noise disturbance

- Responding to stranded pilot whales

- Educating the public about pilot whales and the threats they face

- Monitoring population abundance and distribution

Science

Our research projects have discovered new aspects of pilot whale biology, behavior, and ecology and helped us better understand the challenges that all pilot whales face. This research is especially important in maintaining populations. Our work includes:

- Undertaking stock assessments to determine the status of populations and/or subpopulations

- Measuring the response of animals to sound using digital acoustic recording tags

How You Can Help

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all small whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Do Not Interact with Marine Animals in the Wild

Do not harass, feed, hunt, capture, kill, pursue, approach, surround, swim with, or attempt to touch protected marine wildlife. Never entice protected marine wildlife to approach you.

Do not engage, chase, or try to get a reaction from the animal. Disturbing wildlife interrupts their ability to perform critical functions such as feeding, breeding, nursing, resting, and socializing.

If you’re on a vessel and a marine animal approaches you, put the engine in neutral and allow the animal to continue on its way.

Featured News

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Protecting Species While Planning for Offshore Wind Development in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico

A Rice’s whale just under the surface of the water in the Gulf of Mexico. This endangered whale was recognized as a separate species from the Bryde’s whale in 2021. Credit: NOAA Fisheries under NOAA Permit No. 21938.

A Rice’s whale just under the surface of the water in the Gulf of Mexico. This endangered whale was recognized as a separate species from the Bryde’s whale in 2021. Credit: NOAA Fisheries under NOAA Permit No. 21938.

Celebrate Whale Week with Us: A Message from Janet Coit, Assistant Administrator of NOAA Fisheries

Pair of bottlenose dolphins. Credit: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center/Lisa Morse.

Pair of bottlenose dolphins. Credit: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center/Lisa Morse.

Management Overview

The long-finned pilot whale is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the long-finned pilot whale is listed under:

- Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Interactions with Fishing Gear

Bycatch in fishing gear is a leading cause of long-finned pilot whale deaths and injuries. To reduce deaths and serious injuries from certain commercial fisheries in the western North Atlantic, NOAA Fisheries implemented the Atlantic Pelagic Longline Take Reduction Plan. Representatives from NOAA, the fishing industry, regional fishery management councils, state and federal resource management agencies, the scientific community, and conservation organizations worked together to develop the plan. The plan includes a special research area, gear modifications, outreach material, observer coverage, and captains' communications.

Learn more about bycatch and fisheries interactions

Addressing Ocean Noise

Underwater noise threatens whale populations, interrupting their normal behavior and driving them away from areas important to their survival. Increasing evidence suggests that exposure to intense underwater sound in some settings may cause some whales to strand and ultimately die. NOAA Fisheries is investigating all aspects of acoustic communication and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on whale behavior and hearing. In 2016, we issued technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic (human-caused) sound on marine mammal hearing.

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Long-finned pilot whales have been part of a declared unusual mortality event in the past. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Get information on active and past UMEs

Get an overview of marine mammal UMEs

Educating the Public

NOAA Fisheries aims to increase public awareness and support for pilot whale conservation through education, outreach, and public participation. We regularly share information with the public about the status of pilot whales, as well as our research and efforts to promote their recovery.

Regulatory History

In 2009, NOAA Fisheries implemented the Pelagic Longline Take Reduction Plan, which includes a mainline length requirement as well as research and observer coverage recommendations. The Atlantic Pelagic Longline Take Reduction Team continues to meet and develop recommendations for further reducing bycatch of pilot whales and achieving MMPA goals.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/14/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the long-finned pilot whale. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions for this species.

Stock Assessments

Determining the number of long-finned pilot whales in each population—and whether a stock is increasing or decreasing over time—helps resource managers assess the success of enacted conservation measures. Our scientists collect information and present these data in annual stock assessment reports.

Acoustic Science

Other research is focused on the acoustic environment of cetaceans, including pilot whales. Acoustics is the science of how sound is transmitted. This research involves increasing our understanding of the basic acoustic behavior of whales, dolphins, and fish; mapping the acoustic environment; and developing better methods to locate cetaceans using autonomous gliders and passive acoustic arrays.

Acoustics are used to monitor hearing levels in long-finned pilot whales and feeding behavior. We also study how underwater noise affects the way pilot whales behave, eat, interact with each other, and move within their habitat.

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/14/2025

Research

2024 Northeast Spring Ecosystem Monitoring Cruise Completed

Sampling was expanded off the Mid-Atlantic to capture more plankton for studying ocean acidification.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/14/2025