Rice's Whale

Rice's Whale

Balaenoptera ricei

Protection Status

Quick Facts

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's Whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rice's whales are members of the baleen whale family Balaenopteridae. With likely fewer than 100 individuals remaining, Rice's whales are one of the most endangered whales in the world. Recovery of the species depends upon the protection of each remaining whale.

The Rice's whale has been consistently located in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, along the continental shelf break between 100 and about 400 meters depth. They are the only resident baleen whale in the Gulf of Mexico and are most closely related to Bryde’s (pronounced “broodus”) whales. In 2021, scientists determined that the Rice’s whale was a unique species, genetically and morphologically distinct from Bryde’s whales.

Frequently asked questions about Rice's whales

Population Status

In 2019, NOAA Fisheries listed the Gulf of Mexico Bryde’s whale as an endangered subspecies under the Endangered Species Act. In 2021, NOAA Fisheries revised the common and scientific name of the listed entity to Rice’s whale, Balaenoptera ricei, and classification to species to reflect the new scientifically accepted taxonomy and nomenclature of the species. Like all marine mammals, the Rice’s whale is also protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and given its ESA listing, it is considered depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

When the comprehensive ESA status review was completed in 2016, the team of scientists conducting the ESA status review concluded that there were likely fewer than 100 individual Rice's whales throughout the Gulf, with 50 or fewer being mature individuals. NOAA Fisheries’ most recent abundance estimate from 2017–2018 surveys in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico is approximately 50 individual Rice's whales.

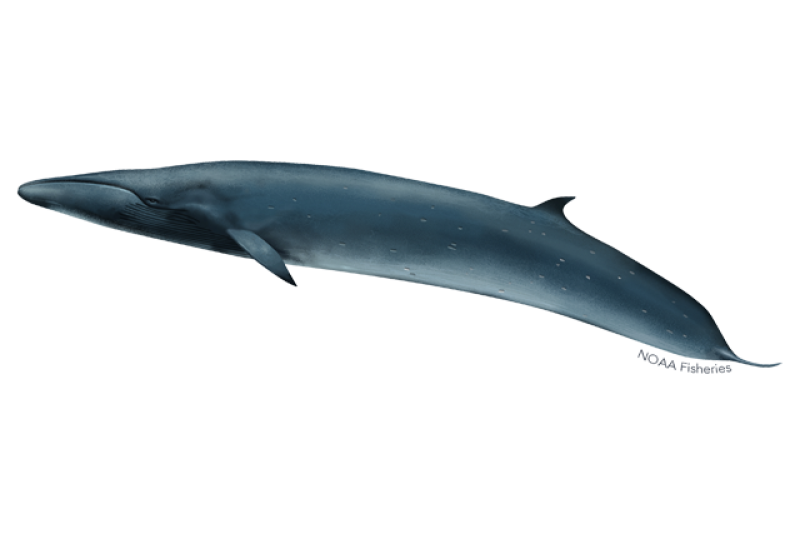

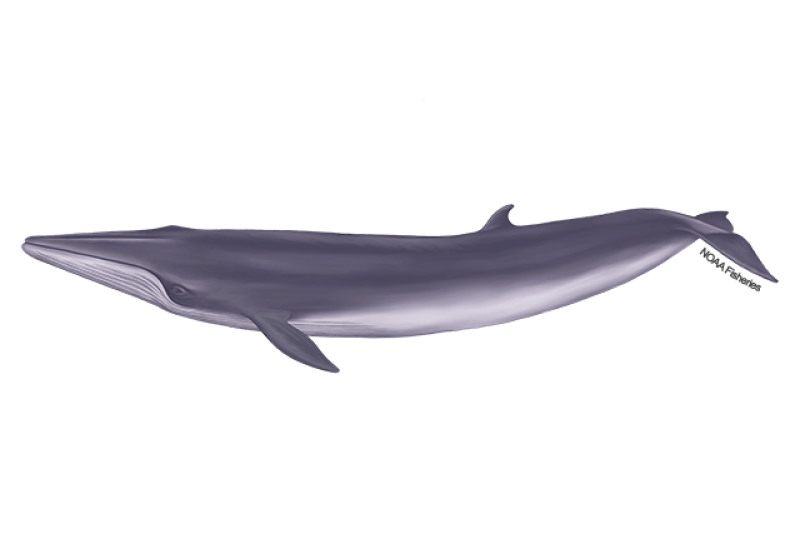

Appearance

Rice's whales, like Bryde’s whales, are smaller than sei whales. Unlike other rorquals, which have a single ridge on their rostrum, Bryde’s and Rice’s whales have three prominent ridges in front of their blowhole, though this feature can be difficult to observe at sea. Their body is sleek, and their pectoral fins are slender and pointed. Rice's whales are uniformly dark gray on top with a pale to pink belly. The head of a Rice's whale makes up about one quarter of its entire body length. The whale has a broad fluke, or tail, and a pointed and strongly hooked dorsal fin located about two-thirds of the way back on its body.

Like other baleen whales, Rice’s whales and Bryde’s whales engulf large amounts of water and strain it through baleen plates that hang inside their mouths to catch their prey. They have throat grooves that expand while feeding to increase the amount of seawater, and therefore prey, that they can engulf.

Behavior and Diet

Rice's whales are usually seen alone or in pairs, but may form larger, loose groups associated with feeding. Limited data suggest that Rice's whales spend the daytime diving near the seafloor bottom and spend the majority of their time at night within 50 feet of the water’s surface, similar to some Bryde’s whales.

Little is known about their foraging ecology and diet. However, data from a two Rice’s whales suggest they may mostly forage at or near the seafloor. This is in contrast to Bryde's whales that have been observed feeding in the water column and near the surface on small crustaceans and schooling fish such as anchovy, sardine, mackerel, and herring.

Baleen whales typically produce a variety of highly stereotyped, low-frequency tonal and broadband calls for communication purposes. NOAA Fisheries scientists are researching what call types the whales produce so that they can use special underwater sound recording instruments to learn more about where these whales go and when..

Where They Live

The historical distribution of Rice's whales may have once encompassed the northern and southern Gulf of Mexico. For the past 25 years, Rice’s whales in U.S. waters of the Gulf of Mexico have been consistently located in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico along the continental shelf between roughly 100 and 400 meters depth. A single Rice’s whale was observed in the western Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Texas, suggesting that their distribution may occasionally include waters elsewhere in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA Fisheries scientists are conducting research to better understand the whales’ distribution, for example, if they utilize the western Gulf of Mexico and Mexican waters of the southern Gulf of Mexico, and how frequently they may occur in these other areas. The Rice's whale is one of the few types of baleen whales to prefer warmer, tropical waters and that does not make long-distance migrations. They remain in the Gulf of Mexico year-round.

World map providing approximate representation of the Rice's whale range (updated June 2019).

World map providing approximate representation of the Rice's whale range (updated June 2019).

Lifespan & Reproduction

Based on information from closely-related Bryde’s whales, Rice's whales are likely able to reproduce every two to three years, reach sexual maturity at age 9, and mate year-round. Based on data from closely related Bryde’s whales, Rice’s whales may be pregnant for 10 to 12 months, and calves may nurse up to 12 months.

Threats

The Rice's whale’s very small population size and limited distribution increase its vulnerability to threats. The most significant threats they face are energy exploration and development, oil spills and spill response, vessel strikes, ocean noise, ocean debris, aquaculture, and entanglement in fishing gear. With such a small population size, the death of a single whale due to any of these stressors could have devastating consequences for the population’s recovery.

Vessel Strikes

Vessel strikes can injure or kill Rice's whales. The northern Gulf of Mexico experiences a high amount of vessel traffic where several commercial shipping lanes cross through Rice’s whale habitat. In 2009, a female Rice's whale was found dead in Tampa Bay. A necropsy was performed and its death was determined to be the result of being struck by a vessel. NOAA Fisheries scientists are studying photos of living whales to evaluate their health which includes estimating how many show evidence of having survived vessel strikes.

Limited data suggest that Rice’s whales spend most of their time within about 50 feet of the water’s surface. The risk of vessel strikes is significant given the location of commercial shipping lanes and other transiting vessel traffic and the whale’s swimming behavior.

Ocean Noise

A variety of human activities in the Gulf of Mexico produce underwater noise. Shipping traffic and energy exploration and development activities, such as seismic airgun surveys to find oil and gas fields, create low frequency noise, which overlaps with the hearing range of Rice’s whales. It is likely that the Rice's whales rely on their hearing to perform critical life functions such as communication, navigation, finding a mate, locating prey, and predator avoidance. As ocean noise levels increase, the resulting habitat degradation and disruption to these life functions can result in adverse physical and behavioral effects to Rice's whales.

Energy Exploration and Development

The Gulf of Mexico is highly industrialized due to expansive oil energy exploration and production that requires seismic surveys, drilling rigs, platforms, cables, pipelines, and vessel support, and in the future, it may also have wind energy development. Habitat in the north-central and western Gulf of Mexico, which likely includes the Rice's whales’ historical range, has already been substantially modified by the presence of thousands of oil and gas platforms and underwater pipelines. These activities also increase risk of vessel strike from support vessels and add noise to the environment from vessel traffic and seismic surveys, as described above.

Oil Spills and Responses

Oil spills are a common occurrence in the Gulf of Mexico. Exposure to oil spills may cause severe illness or death of marine mammals. Oil can coat the baleen that the Rice's whales use to eat. This makes it difficult for them to feed and can cause them to swallow oil. Exposure to oil spills can also lead to lung and respiratory issues (through inhalation), increased vulnerability to other diseases and infections (through ingestion), and irritation of the skin or sensitive tissue in the whale’s eyes and mouths (through absorption). Additionally, exposure to oil spills can have reproductive impacts.

Chemicals used to respond to oil spills, called dispersants, may also be toxic to Rice’s whales. Whales continue to face threats from continued exposure to oil and dispersants in the environment long after the oil spill and spill response are considered over. Additionally, their prey is often killed or contaminated by the spill.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill negatively affected Rice's whales. While the Deepwater Horizon platform was located outside Rice's whale habitat, scientists estimate nearly half of the oil spill footprint overlapped with the whales’ habitat. As a result, it is estimated that their population decreased by 22 percent.

Fisheries and Aquaculture Interactions

Like all large whale species, Rice’s whales can become entangled in fishing and aquaculture gear, which can cause serious injuries and even death. Historically, two Rice's whales stranded, entangled with fishing gear. Since 2003, there have been no known serious injuries or mortalities of Rice's whales due to interactions with fisheries. However, their primary habitat overlaps with several commercial fisheries and their foraging behavior may place them at risk for becoming entangled in certain types of gear. Aquaculture activities have largely been absent from their known habitat; however, that may change in the future as this industry is beginning to expand. NOAA’s Aquaculture Program has identified the Gulf of Mexico as one of the first regions for focused evaluation to find Aquaculture Opportunity Areas. In areas where Bryde’s whales (close relatives of Rice’s whales) and aquaculture gear overlap (e.g., New Zealand), entanglements of whales in aquaculture gear have occurred and led to mortality. Aquaculture activities also increase risk of vessel strike from support vessels, add noise to the environment from vessel traffic, may affect water quality, and attract predators.

Ocean Debris

Rice's whales are also at risk from ocean debris. For example, in 2019 a male Rice's whale washed up along Sandy Key in the Florida Everglades with a hard piece of plastic in its stomach, which is thought to have contributed to its death. Plastic often ends up in the stomachs of marine wildlife, though it is often difficult to determine if it was indeed the cause of death for stranded animals.

Small Population Size and Limited Distribution

The Rice's whale’s very small population size and limited distribution increase its vulnerability to inbreeding (offspring may have traits that put the individual at risk), environmental change, decreased disease resistance, and habitat loss. Due to their limited distribution, these whales are vulnerable to catastrophic events that impact their core habitat, while even the loss of a single individual could prevent recovery due to the very small population size.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetartiodactyla | Family | Balaenopteridae | Genus | Balaenoptera | Species | Ricei |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/04/2024

What We Do

Conservation & Management

Our work to protect and recovery these whales includes:

- Developing recovery plan

- Reducing vessel strikes

- Addressing ocean noise

- Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

- Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Science

NOAA Fisheries continually conducts research to learn more about the biology, behavior, and ecology of Rice's whales to better inform management and policy decisions. Our work includes:

- Monitoring population abundance and distribution

- Stock assessments

- Investigating prey type, distribution, and energetics

- Identifying habitat requirements

- Investigating dive behavior and energy budgets

- Studying acoustics

- Assessing health

How You Can Help

Reduce Speed and Be on the Lookout

Vessel collisions are a major cause of injury and death for whales. Here are some tips to avoid collisions:

Be Whale Aware. Know where whales occur (habitat).

Watch your speed in areas of known marine mammal occurrence. Keep speeds to 10 knots or less to reduce potential for injury.

Keep a sharp lookout. Look for blows, dorsal fins, tail flukes, etc. However, be aware that most captains report never seeing a whale prior to colliding with it.

Protect your boat, protect your passengers. Boats can be heavily damaged and even "totalled" after colliding with a large whale. Collisions can also injure passengers.

Keep your distance. Stay at least 100 yards away.

Stop immediately if within 100 yards. Slowly distance your vessel from the whale.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all large whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

A Rice’s whale in the Gulf of Mexico. Permit #14450. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Laura Dias

A Rice’s whale in the Gulf of Mexico. Permit #14450. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Laura Dias

Three ridges on the rostrum (dorsal head) of this Rice’s whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Laura Dias (Permit #14450)

Three ridges on the rostrum (dorsal head) of this Rice’s whale. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Laura Dias (Permit #14450)

Mother and calf humpback whales near Maui, Hawaii. Humpback whales in the Pacific Ocean swim approximately 3,000 miles from Alaska to Hawaii to spend the winter in the warmer tropical waters. Credit: Jason Moore (NOAA permit #18786)

Mother and calf humpback whales near Maui, Hawaii. Humpback whales in the Pacific Ocean swim approximately 3,000 miles from Alaska to Hawaii to spend the winter in the warmer tropical waters. Credit: Jason Moore (NOAA permit #18786)

In the Spotlight

Rice’s Whale

The Rice’s whale is NOAA Fisheries’ newest Species in the Spotlight. This initiative is a concerted, agency-wide effort launched in 2015 to bring greater attention and marshal resources to save these highly at-risk species.

Scientists have known that these medium-sized baleen whales occur in the Gulf of Mexico for decades. For most of that time, the whales were believed to be a subpopulation of Bryde’s whale, which occurs in other temperate and tropical waters around the globe. After years of research, a team of scientists demonstrated in 2021 that Rice’s whales are genetically and morphologically distinct from Bryde’s whales. Rice’s whales are in fact a unique whale species only found in the Gulf of Mexico. The species was named in honor of Dale W. Rice, the first scientist to write about the whales in 1965.

Rice's whales grow to longer than 40 feet and weigh up to 30 tons. Like Bryde’s whales, Rice’s whales have three parallel ridges on top of their head. This feature distinguishes them from sei, fin, and minke whales, which have a single rostral ridge. They are uniformly gray on top, with a pale to pink belly, and have a strongly hooked dorsal fin. Acoustic research has shown that Rice’s whales communicate using unique vocalizations, or calls, which can be detected with passive acoustic monitoring devices.

NOAA Fisheries listed the Rice’s whale (then known as the Gulf of Mexico Bryde’s whale) as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act in 2019. Rice’s whales are also protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and are considered depleted. The species’ small population size and high extinction risk make it a priority for NOAA Fisheries and our partners to recover.

Where Rice’s Whales Live

Rice’s whales are resident and occur only in the Gulf of Mexico, where they live year-round. Most sightings have been concentrated in the northeastern Gulf off the West Coast of Florida. They have also been seen and heard in the western Gulf offshore of Louisiana and Texas. Areas of predicted habitat exist in the southern Gulf, along the shelf break of Mexico; the extent to which the whales inhabit Mexican waters is unknown. Records of “finback whales” from whaling logbooks in the 18th and 19th centuries suggest Rice’s whales may have been more widely distributed throughout the Gulf of Mexico historically.

Population Status

The species likely numbers fewer than 100 individuals, making it among the most endangered species of whale in the world. The most recent abundance estimate from 2017–2018 surveys in the eastern Gulf of Mexico is approximately 50 individuals. Rice’s whales are one of the marine mammal species that was most heavily impacted by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. A modeling study conducted after the spill estimated that 48 percent of Rice’s whale habitat in the eastern Gulf was exposed to oil. The population declined by as much as 22 percent compared to its pre-spill size. Few calves have been seen during surveys since 2010. There have been frequent observations of individual whales in poor body condition, suggesting there may be lingering effects on reproduction and population growth.

Habitat

Most visual sightings and acoustic detections of Rice’s whales have occurred along the Gulf of Mexico shelf break, in waters that are 100–400 meters deep. Recent tagging and foraging studies indicate the whales dive toward the seafloor during daylight hours. They seek out high-energy prey fish, like the silver-rag driftfish, which occur in large schools along the bottom. At night, the whales appear to spend most of their time near the surface, a behavior that could place them at greater risk of vessel strikes.

Threats

The Gulf of Mexico is highly industrialized and impacted by many human activities. These activities can pose risks to Rice’s whales and their habitat through:

- Vessel strikes

- Noise from vessels and energy exploration

- Oil spills and other pollutants, including lingering effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Ingestion of and entanglement in marine debris

- Climate change and its effect on prey

- Entanglement in fishing gear

The species’ low genetic diversity, small population size, and restricted range further reduces its resilience to threats.

Examples of Threats

In 2009, an adult female Rice’s whale was struck and killed by a ship. Her body was carried into Tampa Bay draped across the ship’s bow. Researchers determined that she was lactating at the time of her death. If she was nursing a calf, her calf probably also died, during or after the strike. In 2019, NOAA scientists photographed a free-swimming Rice’s whale with a severely deformed spine that was likely caused by a vessel strike. In that same year, an adult male Rice’s whale died after ingesting marine debris and washed ashore in southwest Florida. These three observed deaths represent only a fraction of actual mortalities. It is difficult to effectively monitor deaths of Rice’s whales because the whales live far from shore, and we do not regularly conduct surveys in their known habitat.

Species Recovery

We have made tremendous strides in our understanding of Rice’s whales in a short period of time. Several challenges still complicate Rice’s whale recovery, such as:

- Gaps in our scientific knowledge about Rice’s whale life history, demographics and distribution

- Understanding how existing and emerging human activities impact Rice’s whales and their habitat, and how to reduce those impacts

- Limited awareness about the species amongst the public and regional stakeholders

To begin addressing these challenges NOAA Fisheries released a Rice’s Whale Recovery Outline in 2020. It serves as an interim conservation strategy until a full recovery plan is developed. The recovery outline summarizes the key factors that are known (and unknown) about their:

- Biology

- Population status

- Primary threats

- Conservation actions taken to date

It also establishes an interim recovery strategy and action plan, including actions that are needed for research, outreach, and to manage threats.

In 2021, we hosted a virtual, multi-session Rice’s Whale Recovery Planning Workshop (PDF, 49 pages) to gather information, facts, and perspectives on how to recover Rice’s whales. Participants included federal and state agencies, scientific experts, commercial fishery representatives, conservation partners, and non-governmental organizations. Information gleaned from the workshop is being considered as NOAA Fisheries develops the Rice’s Whale recovery plan. We will also be developing a Species in the Spotlight Priority Action Plan to identify priority activities over the next 5 years, which will complement the recovery planning effort.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/04/2024

Management Overview

Rice’s whales are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. NOAA Fisheries listed the Gulf of Mexico Bryde’s whale subspecies in 2019 as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In 2021, we revised the common and scientific name to Rice’s whale, Balaenoptera ricei, and its classification to species to reflect the scientifically accepted taxonomy and nomenclature of the whales. This change to the species and common names does not affect its ESA listing status.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries is required to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. We are committed to the protection and recovery of the Rice’s whale, with the ultimate goal of helping this species recover from its very low population size. This would allow the species to be reclassified from endangered to threatened and ultimately be removed from the list of threatened and endangered species.

Recovery Outline

NOAA Fisheries has developed a recovery outline to serve as an interim guidance document to direct recovery efforts, including recovery planning, for the Rice’s whale until a full recovery plan is developed and approved. The recovery outline presents a preliminary strategy for recovery of the species and recommends high priority actions to stabilize and recover the species.

Recovery Planning Workshops

We conducted a series of virtual recovery planning workshop sessions for the Rice’s whale in October and November 2021. The purpose of the workshops was to gather information, facts, and perspectives on how to recover the Rice’s whale, including identifying potential recovery criteria and actions to address the threats to Rice’s whales. Participants included federal and state agencies, scientific experts, commercial fishery representatives, conservation partners, and non-governmental organizations. The sessions covered the following topics:

- October 18, 2021 – Introduction to Recovery Planning, Species and Threats Overview, ESA Section 7 Effects Analysis Overview, Discussion on Session Topic-Related Recovery Actions and Recovery Criteria

- November 1, 2021 – Climate Change and Renewable Energy, Prey, Entanglement and Fisheries Interactions, Threats Rankings, Discussion on Session Topic-Related Recovery Actions and Recovery Criteria

- November 10, 2021 – Environmental Pollutants and Disease/Health Indicators, Marine Debris, Threats Rankings, Discussion on Session Topic-Related Recovery Actions and Recovery Criteria

- November 16, 2021 – Anthropogenic Noise/Acoustic Habitat, Vessel Collisions, Threats Rankings, Discussion on Session Topic-Related Recovery Actions and Recovery Criteria

- November 18, 2021 – Workshop Recap: Threat Rankings, Recovery Criteria Review and Discussion, Next Steps

Recovery Planning Workshop Summary

Recovery Planning Workshop Summary Appendices

Critical Habitat

Once a species is listed under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries evaluates and identifies whether any marine areas meet the definition of critical habitat. Those areas may be designated as critical habitat through a rulemaking process. A critical habitat designation does not set up a marine preserve or refuge. Rather, federal agencies that undertake, fund, or permit activities that may affect designated critical habitat areas are required to consult with NOAA Fisheries to ensure that their actions do not adversely modify or destroy these designated critical habitats.

On July 24, 2023, NOAA Fisheries proposed to designate critical habitat for the endangered Rice’s whale.

- Proposed rule; request for comments. The comment period has been extended and will now close on October 6, 2023 (88 FR 62522).

- Proposed Rice’s whale critical habitat map

- Draft critical habitat report (PDF, 85 pages)

NOAA Fisheries, Southeast Regional Office held a virtual public hearing on the proposed rule on Thursday, August 24, 2023 from 7:00 p.m.–9:00 p.m (EDT). The public hearing that was canceled due to hurricane Idalia has been rescheduled for Thursday, September 28, 2023, from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. (EDT).

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Vessel Strikes

Collisions between whales and large vessels can injure or kill the whales and damage the vessels, but they often go unnoticed and unreported. The most effective way to reduce collision risk is to keep whales and vessels apart. When this is not possible, the next best thing is for vessels to slow down and keep a lookout for whales to reduce both the likelihood of collisions as well as the potential severity of impact if one occurs. In all but one instance when captains have self-reported a collision with a North Atlantic right whale, the crew reported they never saw a whale before the collision happened.

Learn more about reducing vessel strikes

Addressing Ocean Noise

Low-frequency underwater noise may threaten Rice’s whales by interrupting their normal behavior and driving them away from areas important to their survival, such as feeding areas. NOAA Fisheries is investigating all aspects of acoustic communication and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on whale behavior and hearing. In 2018, we revised technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic (human-caused) sound on marine mammal hearing.

Learn more about underwater noise and marine life

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Rice's whales have been part of a previous unusual mortality event. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Get information on active and past UMEs

Get an overview of marine mammal UMEs

Educating the Public

NOAA Fisheries aims to increase public awareness and support for Rice's whale conservation through education, outreach, and public participation. We share information with the public about the status of Rice's whales, our research, and efforts to promote their recovery.

Key Actions and Documents

Incidental Take Authorization: U.S. Air Force Eglin Gulf Testing and Training

Incidental Take Authorization: U.S. Navy Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing (AFTT) along Atlantic and Gulf Coasts (2018-2025)

Incidental Take Authorization: U.S. Navy Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing (2013 -2018)

Incidental Take Authorization: Oil and Gas Industry Geophysical Survey Activity in the Atlantic Ocean

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/04/2024

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the Rice's whale. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions for this species.

Trophic Interactions and Habitat Requirements of Gulf of Mexico Rice’s Whales

As part of the RESTORE Science Program-funded Gulf of Mexico Rice’s Whale Trophic Ecology Project, we worked with Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Florida International University on a multi-year study to develop a comprehensive ecological understanding of the endangered Rice's whale. In 2018 and 2019, we collected data on the physical, oceanographic, and biological features that may influence Rice’s whale distribution in the Gulf of Mexico. We surveyed mostly within the species’ current core distribution area using a multifaceted approach to collect data.

More about trophic interactions and habitat requirements of Gulf of Mexico Rice's Whales

Stock Assessments

Information from marine mammal stock assessment reports are used to identify and evaluate the status of marine mammal populations and help to design and conduct appropriate conservation measures. Continuing data collection, analysis, and interpretation of Rice's whales is updated and incorporated into annual stock assessment reports.

Shipboard Studies

In addition to surveys supporting stock assessments, we also conduct research cruises to investigate the whales’ habitat preferences, feeding ecology, and to conduct photographic and genetic identification. This research is used to inform management actions that protect the Rice's whale.

Acoustic Science

Acoustics is the science of how sound is transmitted, and NOAA Fisheries works to understand the basic acoustic behavior of whales, dolphins, and fish; map the acoustic environment; and develop better methods to locate cetaceans

Learn more about acoustic science

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/04/2024

Documents

Meet the Rice's Whale

An infographic about the newly described species and one of the most endangered whales in the world

Recovering Threatened and Endangered Species Report to Congress (FY 2021-2022)

This Report to Congress summarizes efforts to recover all transnational and domestic species under…

Rice's Whale Recovery Outline

This document serves as an interim guidance document to direct recovery efforts for the Rice's…

Biological Opinion on the Federally Regulated Oil and Gas Program Activities in the Gulf of Mexico

Programmatic biological opinion on the Gulf of Mexico oil and Gas Program in federal waters…

Research

A density surface model describing the habitat of the Critically Endangered Rice’s whale Balaenoptera ricei in the Gulf of Mexico

This research characterizes habitat for endangered Rice’s whales based on oceanographic parameters…

Rice's Whale Occurrence in the Western Gulf of Mexico from Passive Acoustic Recordings

This research summarizes acoustic detections of Rice’s whales in the western Gulf of Mexico,…

Frequently Asked Questions—Rice’s Whales

Learn about Rice’s whales—their population status, habitat, threats, and other frequently asked questions.

Critically Endangered Rice’s Whales (Balaenoptera ricei) Selectively Feed on High-quality Prey in the Gulf of Mexico

Results from this study indicate that Rice’s whales are selective predators consuming schooling…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 03/04/2024