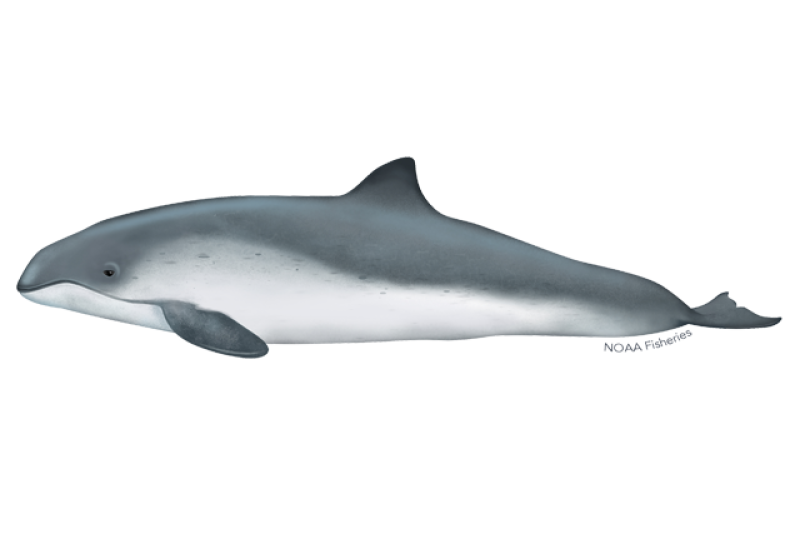

Vaquita

Phocoena sinus

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Vaquita. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Vaquita. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Vaquita. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Vaquita. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Vaquita. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Vaquita. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

The vaquita is a shy member of the porpoise family. Vaquitas are the most endangered of the world’s marine mammals. Less than 20 vaquitas remain in the wild, and entanglement in illegal gillnets is driving the species toward extinction.

Vaquitas have the smallest range of any whale, dolphin, or porpoise. They only live in the northern part of the Gulf of California, an area that is rich in fish and shrimp. Fishing is thus a major source of income for the people there, who almost exclusively use gillnets, but vaquitas can also become accidentally wrapped in the nets and drown.

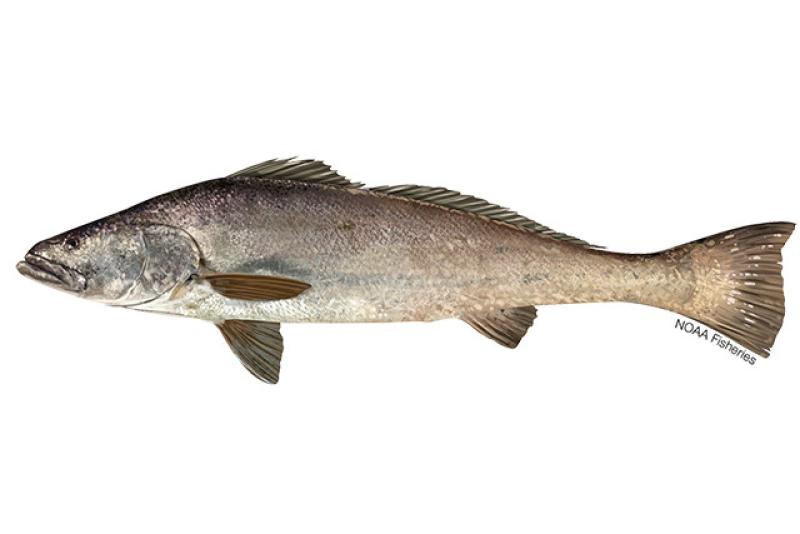

The decrease in the vaquita population is also related to the totoaba, a large fish that also only lives in the Gulf of California. The totoaba is listed as endangered in Mexico and the United States and is protected by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species. Because totoaba and vaquita are similar in size, gillnets illegally set for totoaba are the deadliest for vaquitas. Fishermen illegally catch totoaba for its swim bladder (an air-filled sac in the totoaba’s body that helps it float), which they sell to China at high prices. In China, the swim bladders are used in soup with purported medicinal value. Thousands of swim bladders are dried and smuggled out of Mexico—sometimes through the United States.

Scientists agree that for vaquitas to survive in the wild, gillnet fishing must end within vaquita habitat. The Mexican government has worked with scientists, nongovernmental agencies, and foundations to ban most gillnets. Unfortunately, their actions did not stop the population decline. In April 2015, President Peña Nieto traveled to San Felipe, one of the main fishing towns off the Gulf of California, to announce a 2-year emergency gillnet ban throughout vaquita habitat. The President also announced that the government would pay fishermen for their loss of income. In September 2015, the Mexican government conducted a survey of the vaquita population using both ship-based monitoring and sound-based detectors throughout vaquita habitat.

In July 2017, a federal agreement permanently banned all gillnets except those used for fishing two species: curvina and sierra. But the illegal use of gillnets continues.

Population Status

From 1997, the year of the first complete survey, to 2008, vaquitas declined from around 600 to about 200 individuals as a result of legal fishing. The fishing was largely for shrimp that was mostly exported to the United States. The increased incidence of illegal fishing for a large fish called totoaba around 2011 caused a catastrophic decline of vaquita close to 50 percent of the population per year. Vaquita now number as few as ten animals.

Appearance

The vaquita is about 5 feet long and is one of the smallest members of the dolphin, whale, and porpoise family. Females are longer than males, but males have larger fins.

Vaquitas have small, strong bodies with a rounded head and no beak. They have black patches around their eyes and lips and small, spade-shaped teeth. Vaquitas also have triangle-shaped dorsal fins in the middle of their backs, which are taller and wider than in other porpoises. These fins might allow vaquitas to reduce their body temperatures in warm water. Vaquita backs are dark gray, while their bellies are a lighter gray.

Behavior and Diet

Vaquitas are often found alone or in pairs. These shy animals usually avoid boats with active engines. They are difficult to observe because of their small size, inconspicuous and slow surface rolls, small group size, and avoidance of motorized vessels.

Vaquitas feed on small fish, crustaceans (such as shrimp), and cephalopods (such as squid and octopuses).

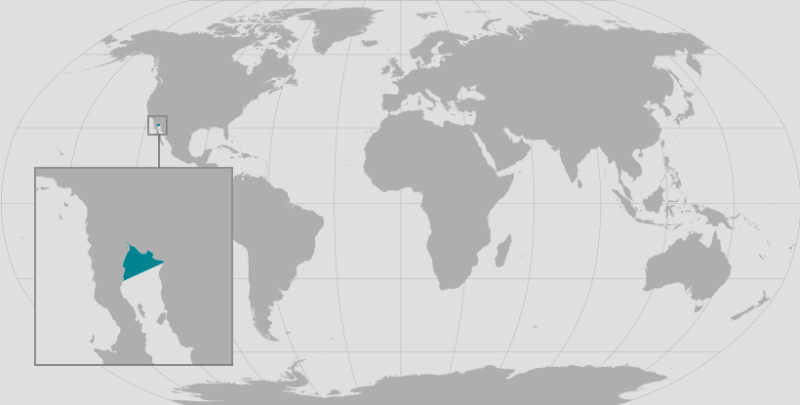

Where They Live

The vaquita has the smallest geographical range of any marine mammal. It only lives in the northern part of the Gulf of California in Mexico. Most vaquitas live east of the town of San Felipe, Baja California, within a 1,519-square-mile area that is less than one-fourth the size of metropolitan Los Angeles. This area also includes the Delta of the Colorado River Biosphere Reserve, one of the earth’s most diverse marine habitats. The delta includes many types of fish, birds, marine reptiles, and marine mammals.

World map providing approximate representation of the vaquita's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the vaquita's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Vaquitas can live for at least 21 years. They reach sexual maturity when they are 3 to 6 years old. Pregnancy lasts about 10 to 11 months, and females are thought to give birth every other year to a single calf that is about 2.5 feet long and 16 pounds. Females usually give birth between February and April.

Threats

Entanglement in Fishing Gear

The only known threat to the vaquita is getting caught in fishing gear, especially gillnets.

Once scientists recognized the vaquita as a species, they also realized that small-scale and commercial fisheries were accidentally catching vaquitas. From the mid-1930s to the mid-1970s, the gillnet fishery for totoaba severely overfished vaquita. Even after this fishery closed in 1975, many vaquitas continued to die in illegal totoaba nets and gillnets set for shrimp and fish.

A study dedicated to estimating the mortality rate of vaquitas from gillnets demonstrated that vaquitas die in every type of gillnet. The highest rate was in totoaba nets, but for many years the numbers of totoaba and totoaba nets were so low that the highest numbers of vaquita deaths were inferred to come from the much more common gillnets set for shrimp. The rate of decline between 1997 and 2008—derived from both visual and acoustic monitoring—is consistent with the level of fishing in this period without inferring any other threat to the species.

Illegal fishing for totoaba has significantly increased since about 2011 due to Chinese demand for its swim bladder. Fishermen can earn up to $8,500 for each kilogram of totoaba swim bladder. This amount is equal to a large percent of a year’s pay from legal fishing.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Artiodactyla | Family | Phocoenidae | Genus | Phocoena | Species | sinus |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 02/28/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

NOAA Fisheries is committed to the protection and recovery of the vaquita. We have focused our conservation efforts on totally eliminating fishing with gillnets within vaquita habitat. NOAA Fisheries, the international recovery team (CIRVA) and the Mexican government recognize that saving vaquitas will require the following actions:

- Permanently banning all gillnets throughout the vaquitas’ range

- Stopping illegal fishing

- Using passive acoustics to annually test the effectiveness of vaquita conservation actions

Science

NOAA Fisheries has provided technical expertise in a close collaboration with Mexican researchers for over 30 years. Early necropsies provided life history and all abundance estimates, both visual and acoustic, have been close collaborations.

The ability to closely monitor this rare and cryptic species has been essential timely science upon which the Government of Mexico can make critical management decisions. Our collaborative work includes:

- Stock assessments

- Ship-based visual monitoring

- Acoustic monitoring

- Genetic research

How You Can Help

Learn About Bycatch

One of the main threats to the vaquita is entanglement in fishing gear, especially gillnets. Fishermen sometimes catch and discard animals they do not want, cannot sell, or are not allowed to keep. This is collectively known as bycatch.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Do Not Interact with Marine Animals in the Wild

Do not harass, feed, hunt, capture, kill, pursue, approach, surround, swim with, or attempt to touch protected marine wildlife. Never entice protected marine wildlife to approach you.

Do not engage, chase, or try to get a reaction from the animal. Disturbing wildlife interrupts their ability to perform critical functions such as feeding, breeding, nursing, resting, and socializing.

If you’re on a vessel and a marine animal approaches you, put the engine in neutral and allow the animal to continue on its way.

Featured News

A timeline of one totoaba specimen’s journey from the illegal wildlife trade to its final resting place as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Fish Collection. Credit: Sandra Graubard/NOAA Fisheries

A timeline of one totoaba specimen’s journey from the illegal wildlife trade to its final resting place as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Fish Collection. Credit: Sandra Graubard/NOAA Fisheries

The Endangered Species Act: 50 Years of Conserving Species

Pair of bottlenose dolphins. Credit: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center/Lisa Morse.

Pair of bottlenose dolphins. Credit: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center/Lisa Morse.

U.S. Proposes Strong Protections for Sea Turtles, Totoaba, and Vaquita at CITES Meeting

Management Overview

The vaquita is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

The vaquita is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

The vaquita is depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the vaquita is listed under:

- Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Recovery Planning and Implementation

A U.S. recovery plan has not been written because an international recovery team is responsible for providing recommendations to the Mexican government (see Conservation Efforts section).

Conservation Efforts

Creating the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita

The Mexican government has created the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA). NOAA Fisheries and its partners participate in CIRVA. Because vaquitas are so close to extinction, CIRVA has met every 5 to 6 months since 2015 to discuss the status of the vaquita population and explore conservation efforts. Some of CIRVA’s most recent recommendations for protecting vaquita from extinction are detailed below.

Increasing Enforcement and Prosecution

Fishermen continue to fish illegally for totoaba in the Gulf of California. The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, in collaboration with the Mexican Navy, has removed many totoaba nets from the gulf. Because illegal fishing is still a problem, CIRVA recently recommended that the Mexican government and its partners increase enforcement efforts to stop illegal totoaba fishing.

Banning Gillnets

Scientists agree that the only way to save the vaquita in the wild is to totally end gillnet fishing within its habitat. Mexico is responding to this crisis and breaking new ground in conservation activities. The Mexican government has worked with scientists, nongovernmental agencies, and foundations to ban gillnets. In April 2015, President Peña Nieto traveled to San Felipe, one of the main fishing towns off the Gulf of California, to announce a 2-year emergency gillnet ban throughout vaquita habitat.

Unfortunately, their actions did not stop the vaquita’s decline. CIRVA then recommended that the government extend the ban to include nearby areas. The Mexican government published regulations that permanently banned the sale or possession of most gillnets, with exemptions for two fish species, in June 2015. In addition, the Mexican government also passed a law making some illegal fishing practices a felony punishable by imprisonment; however, as of June 2017, no one has been jailed for illegal totoaba activities.

Exploring Alternative Fishing Gear

Gillnets are the only threat to vaquitas. Mexican fisheries researchers have developed and tested some alternative fishing gear, with limited help from NOAA Fisheries and its partners. The objective is to create new fishing methods that do not use gillnets and to train fishermen to use these new fishing methods.

Establishing a Protective Sanctuary

In April 2017, CIRVA recommended that as many vaquitas as possible be removed as quickly as possible and taken into protective sanctuary. Mexico worked with the National Marine Mammal Foundation to form a new team of scientists—the Consortium for Vaquita Conservation, Protection and Recovery (VaquitaCPR)—to carry out this effort. NOAA Fisheries supports VaquitaCPR by providing expertise in finding vaquitas and helping to care for them along with a team of 40 scientists from Denmark to Hong Kong. This effort aims to capture vaquitas and bring them into human care in late 2017, protecting them from entanglement until the Upper Gulf is gillnet-free and it is safe to release vaquitas into the wild again.

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event (UME) is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Regulatory History

In 1985, vaquita were listed as endangered under the ESA.

In July 2017, a federal agreement permanently banned all gillnets within the vaquita's range in the Gulf of California, except those used for fishing two species: curvina and sierra.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 02/28/2025

Science Overview

NOAA and Mexican scientists collaborate to answer key questions about the vaquita. Current research focuses on abundance and abundance estimation. These efforts include:

- Population assessments

- Bycatch estimates

- Ship-based visual monitoring

- Acoustic monitoring

Bycatch Estimates

Fishermen sometimes catch and kill animals that are not their target species, such as vaquitas. This is known as bycatch. Fishermen can accidentally catch vaquitas in gillnets for fish and shrimp. Vaquitas drown once entangled in these nets. Only one study has tried to count the number of vaquitas that died in gillnets. This study took place from 1993 to 1994 at one of the three main fishing ports in the Gulf of California. The authors gathered data from observations and interviews with fishermen and estimated that 39 vaquitas were killed in gillnets that year in the port.

Learn more about bycatch estimates

Ship-Based Visual Monitoring

Scientists conducted full abundance estimates of vaquitas in 1997, 2008, and 2015. The last full survey took place from September to December 2015. Scientists came from Mexico, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany to participate in the expedition. They surveyed the deeper water distribution of vaquitas from a research ship using six huge binoculars, called “big eyes.” These binoculars allow scientists to see the shy vaquitas before they react to the ship.

Learn more about ship-based visual monitoring

Acoustic Monitoring

Acoustics monitoring estimates vaquita abundance trends by studying the echolocation clicks that vaquitas use to find their food. Mexico is a world leader in acoustic monitoring of vaquitas. Scientists use a device called a CPOD, which can pick up the high-pitch vaquita clicks for months at a time, to gather over 3,000 days of data each year. In 2015, scientists placed 134 CPODs in a grid around the vaquita habitat. Because the CPODs can be placed in shallow water, they allow scientists to monitor vaquitas in areas where ships cannot go. In the area of greatest vaquita density, scientists conducted both acoustic monitoring and visual surveys, calibrating the acoustic monitoring to the densities of vaquitas seen. The CPODs allow researchers to develop new estimates of vaquita abundance each year. For example, only about half the number of clicks were detected in 2016. Since vaquitas were estimated to have only about 60 individuals in 2015, the acoustic data mean there were only about 30 individuals in 2016. Scientists will continue this important research to collect more information about current population status.

Learn more about acoustic science

Read the research summary of the 2015 expedition

Population Assessments

Determining the number of vaquita in the wild—and how the population is changing over time—helps resource managers measure the effects of conservation actions. Data are collected using visual line transect surveys and passive acoustic monitoring.

More Information

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 02/28/2025