Where does the Atlantic surfclam grow the fastest? How will this species respond to global change, including ocean acidification, over the long term? These questions drive us to study surfclam growth around Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

March was a busy month at the Northeast Fisheries Sciences Center’s Milford Laboratory. Our team has been working to set up an experiment we’ve been planning all winter. Now that the ice has melted, we are ready.

Since last summer, we've been visiting a number of sites on Cape Cod. At each site we look for surfclams and sample the seawater. We’re interested in the environmental conditions that the clams live in, such as the water they pull through their mantles to filter feed. We also look at the water they’re exposed to within the sand, called sediment pore-water. We hope to find out if their growth rate correlates with the chemistry of the sediment they burrow into.

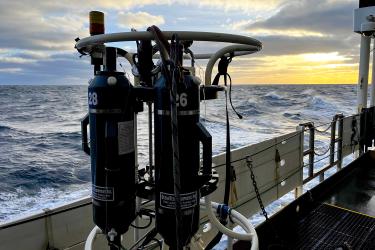

Massachusetts Maritime Academy students are a major part of our team. Along with their capable boating skills, these students bring their enthusiasm for environmental chemistry and marine operations.

This March we prepared for a transplant experiment in which we will grow two subspecies of surfclams in enclosures. This will help us to better understand the role of the environment versus population on their growth. To better understand the role of the environment on growth, we will compare the growth of the northern subspecies at different sites. At one southern Cape Cod site that has a large population of the southern subspecies we will also compare the growth of the two subspecies.

Meanwhile, I’ve been crushing surfclam shell into small (less than 4 millimeter) pieces. We will mix the shell into the sand within the enclosures. We think adding this calcium carbonate shell may change the chemistry of the water between the grains of sand.

One side effect of fossil fuel pollution is known as ocean acidification. When carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from fossil fuels dissolves into seawater, this increases the acidity of the seawater, making it less basic (or alkaline). We think that adding shell might alleviate stress on the surfclams caused by this change in chemistry of the seawater.

We made it out into the field to install our enclosures, but unfortunately our anchors did not arrive on time. This setback gave us time to test deploying the enclosures at the different sites before the final installation, which will include 32 enclosures at each site.

The transplant experiment will last 9 to 12 months and include at least three sampling periods. We’ll study the growth of the surfclams and monitor their environment during this time. We’ll use the data we collect to validate a model of surfclam growth and reproduction under different ocean conditions. We then plan to use this model to predict the effect of ocean warming and ocean acidification on surfclam growth at these sites.

The end!