I just got back from my first trip for this fall’s Gulf of Maine Cooperative Bottom Longline Survey. I sailed on the F/V Mary Elizabeth, a commercial fishing vessel we work with on the survey. It’s a boat I’ve been going out on since 2014, back when I was a fisheries observer.

We left Scituate, Massachusetts, and headed east to the edge of the Hague Line—the international boundary that divides U.S. and Canadian waters on Georges Bank. It’s about 200 nautical miles from land. As I waved goodbye to Old Scituate Lighthouse and left the safety of the harbor, the large swells started. My stomach was doing flips the entire 20-hour steam out, and I’ll admit I threw up more than once.

Usually on the steam out I like to watch for birds and whales. But it was chilly and I sat sullen at the galley table, where the warmth from the smokestack behind the wall warmed my back. I was also perfectly positioned near the door in case I needed to make a quick exit to the back deck again.

When I wasn’t feeling so ill, I passed the time reading Stephen King’s The Institute and telling groan-worthy jokes to survey chief scientist Dave McElroy, much to his chagrin. I also soaked in all the glorious sunsets that can’t be beat when you’re offshore! I always look forward to sailing on the F/V Mary Elizabeth, no matter the weather. I always have a fun time—that’s the difference a great captain and crew make.

Once we arrived at the first sampling station, the weather had calmed down, thankfully. We mostly caught Atlantic spiny dogfish, a good mix of white hake, cusk, barndoor skates, and a few nice sized Atlantic cod, which was great to see. We recorded weights and lengths on everything and took biological samples—otoliths and gonad tissue—from certain flagged species or individuals. Otoliths are ear bones in fish that have growth rings, like trees, that scientists use to age fish. We also gathered weight and tissue samples from the female ovaries to later help determine maturity.

Cutting open fish can get a bit messy, so we rotate between data recording and fish dissection. It helps keep the workload more evenly distributed, especially when your arms get tired cutting through hard-headed fish like cusk. True fact: whoever is doing the data recording gleefully laughs internally when a large haul of cusk comes up. That said, karma always seems to have a way of sorting things out in the end.

As we worked our way back west, the catches seemed to get progressively lighter and we caught some species that we don’t see as often, like monkfish and Acadian redfish. We also had to contend with a blue shark at our sampling site more than once. The captain tried to haul the longline gear faster to prevent the shark from stealing the catch, but it managed to mangle a few fish before we were able to get all the gear on deck. During one haul, the persistent shark even cut the longline.

Besides seeing a blue shark, we also saw dolphins and an ocean sunfish, but the sightings were too short to get any decent footage. However, we did get footage of something else, something really cool.

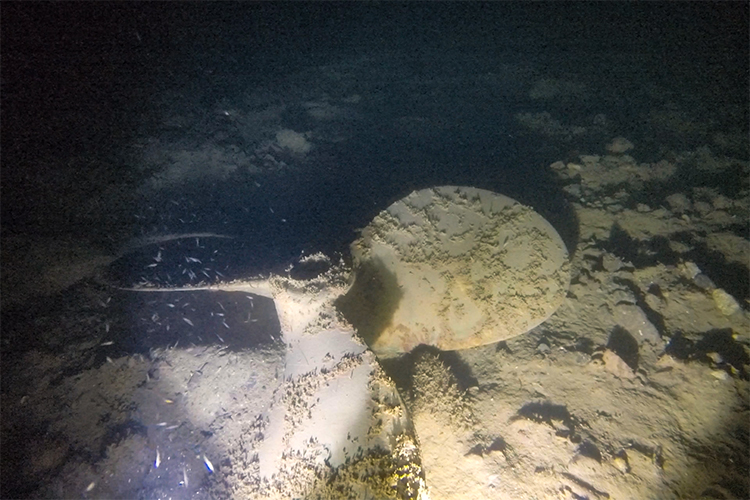

At every sampling station we send a camera down to record what the seafloor bottom looks like. This time we found a propeller! The captain estimated that it might be about 36 inches and from a boat that’s a similar size to the F/V Mary Elizabeth, roughly 50 to 60 feet long. It makes you wonder about the poor soul who lost it—so far away from land—and how long they waited for rescue. Not too many boats make it this far east. The chances that we would drop a camera in the exact same spot have to be incredibly low. It makes me excited for what we’ll find on the next trip.