Bryde’s Whale

Balaenoptera edeni

Protected Status

Quick Facts

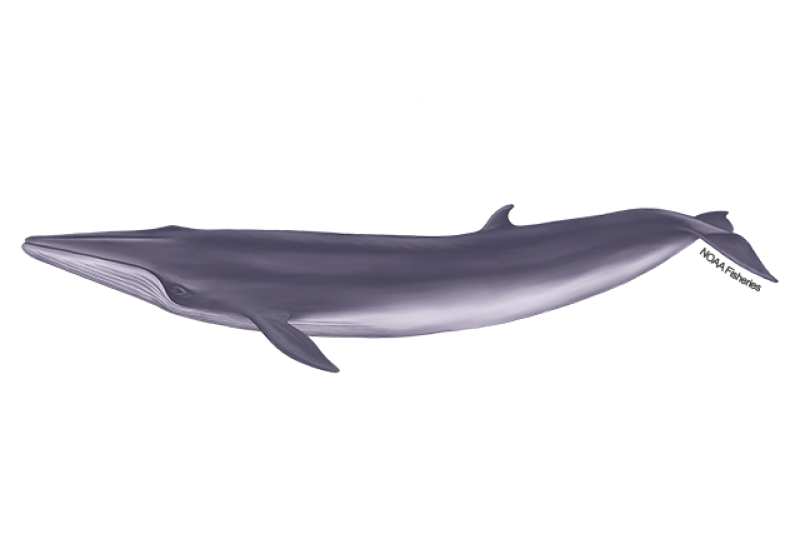

Bryde's whale swimming in the ocean. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Bryde's whale swimming in the ocean. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Bryde's whale swimming in the ocean. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Bryde's whale swimming in the ocean. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Bryde's whale swimming in the ocean. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Bryde's whale swimming in the ocean. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Bryde's (pronounced "broodus") whales are members of the baleen whale family. They are considered one of the "great whales," or rorquals, which is a group that also includes blue whales and humpback whales. Bryde’s whales are named for Johan Bryde, a Norwegian who built the first whaling stations in South Africa in the early 20th century.

Bryde’s whales are found in warm, temperate oceans including the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific. Some populations of Bryde's whales make short migratory movements with the seasons, while others do not migrate, making them unique among other migrating baleen whales.

Bryde’s whales are vulnerable to many stressors and threats, including vessel strikes, ocean noise, and whaling outside the United States.

All Bryde’s whales are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Population Status

NOAA Fisheries estimates population size and trends in our stock assessment reports. At this time, there is not enough information to estimate population trends for the Bryde’s whale species as a whole.

Bryde’s whales are currently considered monotypic (belonging to one species). Currently, there are two subspecies of Bryde’s whales. Eden’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni) is a smaller form found in the Indian and western Pacific oceans, primarily in coastal waters. The Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni brydei) is a larger form, found primarily in pelagic waters. The Bryde's whale's "pygmy form" was identified in the late 1970s and early 1980s has been described as a separate species, Omura's whale (Balaenoptera omurai).

Each subspecies has a different geographic distribution, genetic makeup, habitat, and physical appearance. Researchers are discussing whether the science supports recognizing the two subspecies as full species or whether additional data are needed to make that determination.

Appearance

Bryde’s whales look similar to sei whales but are smaller and prefer warmer waters. Unlike other rorquals, which have a single ridge on their rostrum, Bryde’s whales have three prominent ridges in front of their blowhole. Their bodies are sleek and their flippers are slender and pointed.

The head of a Bryde's whale makes up about one quarter of its entire body length. The whales have a broad fluke, or tail, and a pointed and strongly hooked dorsal fin located about two-thirds back on the body. Bryde’s whales have 40 to 70 throat grooves on their underside that expand while feeding and 250 to 410 gray, coarse baleen plates on each side of their mouths that act as strainers while they feed. Male Bryde’s whales are usually slightly smaller than females.

Behavior and Diet

Bryde’s whales are usually seen alone or in pairs. Nonetheless, there have been reports of up to 20 whales loosely grouped together in feeding areas.

Research suggests that Bryde’s whales spend most of the day within 50 feet of the water’s surface. They commonly swim at 1 to 4 miles per hour but can reach speeds of 12 to 15 miles per hour. They dive for about 5 to 15 minutes, with a maximum dive duration of 20 minutes, and can reach depths up to 1,000 feet. They do not display their flukes when diving.

Bryde’s whales eat an estimated 1,320 to 1,450 pounds of food per day. Their diet consists of krill, copepods, red crabs, shrimp, as well as a variety of schooling fish, such as herring, mackerel, pilchards, and sardines. Bryde's whales use different methods to feed in the water column, including skimming the surface, lunging, and creating bubble nets.

Bryde’s whales can blow water 10 to 13 feet into the air when at the water’s surface. They sometimes exhale while underwater as well. Additionally, Bryde’s whales can change directions unexpectedly when swimming. They sometimes generate short, powerful sounds that have low frequencies and sound like "moans."

Where They Live

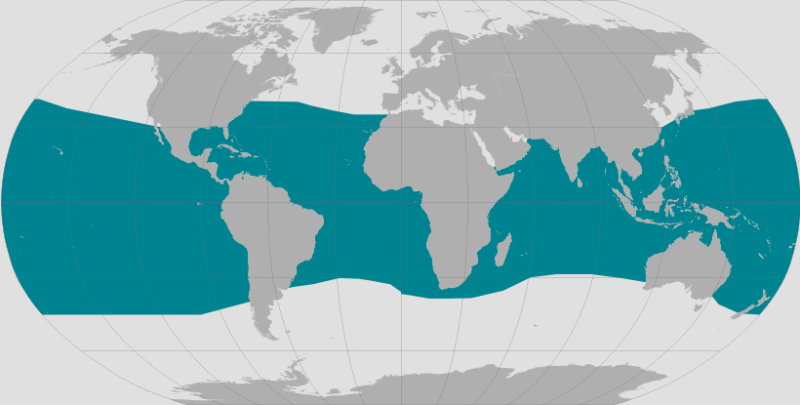

Bryde's whales have a wide distribution and occur in tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate waters (61° to 72°F) around the world. They live in all oceans from 40° south to 40° north. Some populations of Bryde's whales migrate with the seasons, moving away from the equator during the summer and towards the equator during the winter. Other populations of Bryde's whales are residents, meaning that they do not migrate.

World map providing approximate representation of the Bryde's whale range

World map providing approximate representation of the Bryde's whale range

Lifespan & Reproduction

Bryde's whales become sexually mature at around nine years of age and can mate year-round. The peak of the breeding and calving season occurs in autumn, and females give birth to a single calf every two to three years. Pregnancy lasts 10 to 12 months, and calves nurse for about 12 months.

Threats

Bryde’s whale populations are exposed to a variety of stressors and threats, including vessel strikes, ocean noise, and whaling outside the United States.

Vessel Strikes

Accidental vessel strikes can injure or kill Bryde’s whales. They are vulnerable to vessel strikes throughout their range, but the risk is much higher in coastal areas with heavy vessel traffic. Bryde's whales are the third most commonly reported species struck by vessels in the southern hemisphere.

Ocean Noise

Low-frequency underwater noise pollution can interrupt Bryde’s whales’ normal behavior by hindering their ability to use sound, causing a disruption of their ability to communicate, choose mates, find food, avoid predators, and navigate.

Whaling (Outside the United States)

Historically, Bryde’s whales were not major targets for commercial whaling. However, whalers have recently hunted Bryde’s whales off the coasts of Indonesia and the Philippines. Additionally, some hunters in Japan continue to take Bryde’s whales as part of their scientific research whaling program.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Balaenopteridae | Genus | Balaenoptera | Species | edeni |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 06/23/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

All Bryde’s whales are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Our work supports the protection and conservation of the Bryde’s whale by:

- Minimizing the effects of vessel disturbance, noise, and other types of human effects

- Responding to stranded Bryde’s whales

- Educating the public about Bryde’s whales and the threats they face

Science

NOAA Fisheries conducts scientific research to learn more about the biology, behavior, and ecology of Bryde’s whales to better inform management and policy. Our work includes:

- Stock assessments

- Monitoring population abundance and distribution

How You Can Help

Reduce Speed and Be on the Lookout

Vessel collisions are a major cause of injury and death for whales. Here are some tips to avoid collisions:

Be Whale Aware. Know where whales occur (habitat).

Watch your speed in areas of known marine mammal occurrence. Keep speeds to 10 knots or less to reduce potential for injury.

Keep a sharp lookout. Look for blows, dorsal fins, tail flukes, etc. However, be aware that most captains report never seeing a whale prior to colliding with it.

Protect your boat, protect your passengers. Boats can be heavily damaged and even "totalled" after colliding with a large whale. Collisions can also injure passengers.

Keep your distance. Stay at least 100 yards away.

Stop immediately if within 100 yards. Slowly distance your vessel from the whale.

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all large whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

Kathi George participating in whale disentanglement training. Credit: Bill Hunnewell/The Marine Mammal Center

Kathi George participating in whale disentanglement training. Credit: Bill Hunnewell/The Marine Mammal Center

Pilot whales surface near the NOAA Ship Gordon Gunter. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Melody Baran (Permit # 14450)

Pilot whales surface near the NOAA Ship Gordon Gunter. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Melody Baran (Permit # 14450)

Management Overview

The Bryde’s whale is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the Bryde’s whale is listed under:

- Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Vessel Strikes

Collisions between whales and large vessels can injure or kill the whales and damage the vessels, but they often go unnoticed and unreported. The most effective way to reduce collision risk is to keep whales and vessels apart.

Learn more about reducing vessel strikes

Addressing Ocean Noise

Low-frequency underwater noise may threaten Bryde’s whales by interrupting their normal behavior and driving them away from areas important to their survival, such as feeding waters. Mounting evidence suggests that exposure to intense underwater sound in some settings may cause some whales to strand and ultimately die. NOAA Fisheries is investigating all aspects of acoustic communication and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on whale behavior and hearing. In 2016, we issued technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic (human-caused) sound on marine mammal hearing.

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Bryde’s whales have never been part of a declared unusual mortality event. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Regulatory History

All marine mammals, including Bryde’s whales, are protected in the United States under the MMPA.

Key Actions and Documents

Incidental Take Authorization: Scripps Institution of Oceanography's Marine Geophysical Survey in the Nauru Basin of Greater Micronesia in the NW

Incidental Take Authorization: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Marine Geophysical Survey of the Chain Transform Fault in the Equatorial Atlantic

Incidental Take Authorization: U.S. Navy Hawaii-Southern California Training and Testing (HSTT) (2018-2025)

- Final Rule (2025)

- Proposed Rule (2023)

- Notice of Receipt of Application for Revision to 7-Year Rule and LOAs (2022)

- Final 7-Year Rule (2020)

- Proposed 7-Year Rule (2019)

Incidental Take Authorization: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Marine Geophysical Surveys of the Guerrero Gap off the Coast of Mexico in the Eastern

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 06/23/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the Bryde’s whale. The results are used to inform management decisions for this species.

Stock Assessments

Determining the size of Bryde’s whale populations helps resource managers determine the success of conservation measures. Our scientists collect population information and present the data in annual stock assessment reports.

Acoustic Science

Acoustics is the science of how sound is transmitted. NOAA researchers measure the acoustic environment of cetaceans to increase our understanding of the basic acoustic behavior of whales, dolphins, and fish; mapping the acoustic environment; and developing better methods to locate cetaceans using autonomous gliders and passive acoustic arrays.

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 06/23/2025

Documents

Rice's Whale Recovery Outline

This document serves as an interim guidance document to direct recovery efforts for the Rice's…

Status Review of Bryde's Whales in the Gulf of Mexico Under the Endangered Species Act

This status review responds to a September 18, 2014 petition from the Natural Resources Defense…

Research

Bryde’s Whales Produce Biotwang Calls, Which Occur Seasonally in Long-Term Acoustic Recordings From the Central and Western North Pacific

Results provide evidence for a pelagic western North Pacific population of Bryde’s whales with…

An Unknown Nocturnal Call Type in the Mariana Archipelago

In spring/summer of 2018 and 2021, the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center Cetacean Research…

Genetic Evidence Reveals a Unique Lineage of Bryde's Whales in the Northern Gulf of Mexico

Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships were characterized for this unique group of whales…

Spatial Distribution and Dive Behavior of Gulf of Mexico Bryde's Whales: Potential Risk of Vessel Strikes and Fisheries Interactions

Evaluating the potential overlap of commercial shipping and commercial fisheries with Gulf of…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 06/23/2025