Hector’s Dolphin

Cephalorhynchus hectori

Protection Status

Quick Facts

Hector’s dolphin, Banks Peninsula. ©Steve Dawson, NZ Whale and Dolphin Trust

Hector’s dolphin, Banks Peninsula. ©Steve Dawson, NZ Whale and Dolphin Trust

Hector’s dolphin, Banks Peninsula. ©Steve Dawson, NZ Whale and Dolphin Trust

About the Species

Hector’s dolphin, Banks Peninsula. ©Steve Dawson, NZ Whale and Dolphin Trust

Hector’s dolphin, Banks Peninsula. ©Steve Dawson, NZ Whale and Dolphin Trust

Hector’s dolphin, Banks Peninsula. ©Steve Dawson, NZ Whale and Dolphin Trust

Hector’s dolphin is one of the world’s smallest dolphins and is found only in the coastal waters of New Zealand. Two subspecies of Hector’s dolphins have been formally recognized based on multiple morphological distinctions and genetic evidence of reproductive isolation. One subspecies with the common name of Hector's dolphin occurs in the waters around the South Island of New Zealand. The other subspecies known as the Māui dolphin, or Maui’s dolphin, occurs only in waters off the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. Substantial declines in this species have been detected for most populations, mainly as a result of bycatch in gillnets. In 2017, NOAA Fisheries listed the Māui dolphin subspecies as endangered and the Hector’s dolphin subspecies as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Appearance

Hector's dolphins are among the smallest dolphins in the world. They have short and stocky bodies, no external beak, and a relatively large fluke. Both subspecies typically have a total body length of four to five feet at maturity, with Māui dolphins reaching a larger size than Hector’s dolphins and females of both subspecies reaching larger sizes than males. They have a very rounded dorsal fin and paddle-like pectoral fins. Their distinctive gray, black, and white coloring changes as the dolphin ages from a newborn calf into an adult. As an adult, the sides of the head, tail, dorsal fin, and flippers are black; the throat, lower jaw, and belly are white; and most of the rest of the body is gray. A thin black line also curves from the head to just behind the blowhole. They have 26 to 32 pairs of small, conical teeth in the upper and lower jaws.

Behavior and Diet

Hector’s dolphins occur in small groups averaging two to four dolphins and up to 20 dolphins. Hector’s dolphins display a wide range of behaviors, including body contacts, bubble-blowing, leaping, lobtailing (slapping the water surface with the fluke), and spyhopping (holding the body vertically with head above the water surface). Generally, they are less active in terms of jumping compared to some other species (e.g., spinner and dusky dolphins).

Hector's dolphins have a varied diet that includes cephalopods, crustaceans, and small fish species. Species such as red cod, ahuru, arrow squid, sprat, sole, and stargazer comprise the bulk of their diet.

Where They Live

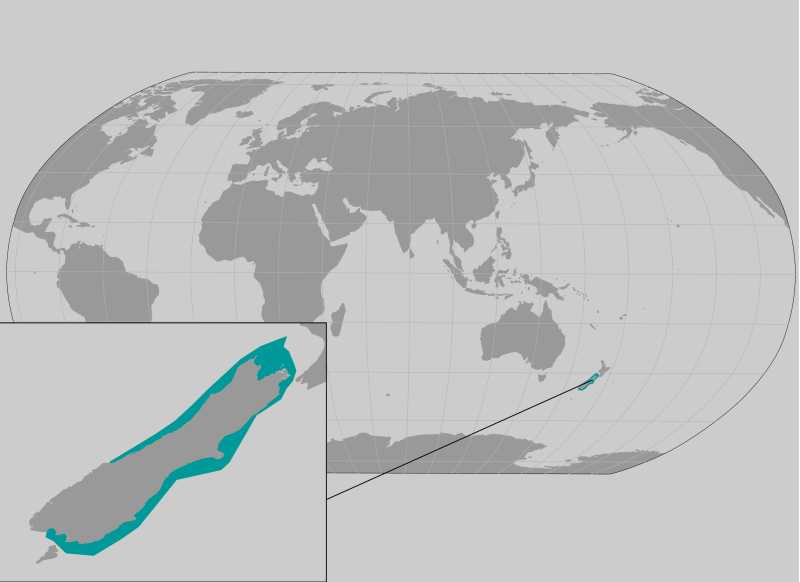

Hector’s dolphins are coastal dolphins native to New Zealand. Māui dolphins are currently found only along the northwest coast of the North Island, between Maunganui Bluff and Whanganui. The South Island Hector’s dolphins are found in the waters around the South Island and consist of at least three genetically distinct, regional populations. Hector’s dolphins are typically sighted within about 20 nautical miles of the coast and in water less than 328 feet deep. Hector’s dolphins have relatively small home ranges (typically less than about 31 miles) and high site fidelity, although some longer movements appear to be possible (e.g., over about 250 miles).

World map providing approximate representation of Hector's dolphin's range.

World map providing approximate representation of Hector's dolphin's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Maximum age is at least 22 years and sexual maturity is reached at about 6 to 9 years of age. Females typically produce single calves every 2 to 4 years, and calves remain with their mothers for 1 to 2 years, although 2 years is more common.

Threats

The largest threat to both subspecies is bycatch in commercial and recreational gillnets and trawls. Habitat-related threats, disease, and tourism may also negatively impact the dolphins. Fisheries restrictions and other management efforts have gradually increased over time; however, both subspecies are still expected to decline. Low population growth rates also contribute to the dolphins’ vulnerability.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetacea | Family | Delphinidae | Genus | Cephalorhynchus | Species | hectori |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/08/2022

Featured News

Pair of bottlenose dolphins. Credit: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center/Lisa Morse.

Pair of bottlenose dolphins. Credit: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center/Lisa Morse.

Gray whales were nearly hunted to extinction by commercial whaling. Protections under the MMPA, ESA, and the end of commercial whaling have allowed the species to recover. Credit: NOAA Fisheries (Permit #19091).

Gray whales were nearly hunted to extinction by commercial whaling. Protections under the MMPA, ESA, and the end of commercial whaling have allowed the species to recover. Credit: NOAA Fisheries (Permit #19091).

Finback whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Finback whales. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Management Overview

In 2017, NOAA Fisheries listed the Hector’s dolphin subspecies as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Conservation Efforts

Dolphin-Safe/Tuna Tracking and Verification Program

Dolphins, like other marine mammals, may become bycatch in fisheries. Some species of tuna are known to aggregate beneath schools of certain dolphin stocks. In some parts of the world, this close association led to the fishing practice of encircling a dolphin school to capture the tuna concentrated below. The Dolphin Protection Consumer Information Act established a national tuna tracking program to ensure that tuna imported into the United States meets certain requirements to ensure the safety of dolphins during tuna fishing operations.

Learn more about the Dolphin-Safe/Tuna Tracking and Verification Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event (UME) is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Regulatory History

In July 2013, NOAA Fisheries received a petition to list Hector's dolphin as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. In February 2014, we concluded that the petition presented substantial information that listing may be warranted for Hector’s dolphin and requested information on this species from the public. After completing a status review, we proposed to list the Māui dolphin as endangered and the South Island Hector’s dolphin as threatened. On September 19, 2017, after reviewing the best available data, NOAA Fisheries published a final rule listing the Māui dolphin as endangered and the South Island Hector’s dolphin as threatened.

Key Actions and Documents

Incidental Take Authorization: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Marine Geophysical Surveys in the Southwest Pacific Ocean

More Information

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/08/2022

Documents

Status Review Report For Hector's Dolphin (Cephalorhynchus hectori)

This document is the scientific review of the biology, status, and future outlook for…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/08/2022