Shortnose Sturgeon

Shortnose Sturgeon

Acipenser brevirostrum

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River, CT. Copyright: Robert S. Michelson/Photography by Michelson, Inc.

Shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River, CT. Copyright: Robert S. Michelson/Photography by Michelson, Inc.

Shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River, CT. Copyright: Robert S. Michelson/Photography by Michelson, Inc.

About the Species

Shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River, CT. Copyright: Robert S. Michelson/Photography by Michelson, Inc.

Shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River, CT. Copyright: Robert S. Michelson/Photography by Michelson, Inc.

Shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River, CT. Copyright: Robert S. Michelson/Photography by Michelson, Inc.

Shortnose sturgeon live in rivers and coastal waters from Canada to Florida. They hatch in the freshwater of rivers and spend most of their time in the estuaries of these rivers. Unlike Atlantic sturgeon, shortnose sturgeon tend to spend relatively little time in the ocean. When they do enter marine waters, they generally stay close to shore. In the spring, adults move far upstream and away from saltwater to spawn. After spawning, the adults move rapidly back downstream to the estuaries, where they feed, rest, and spend most of their time.

Shortnose sturgeon have five rows of external, bony plates along the length of their body known as scutes, giving them the appearance they are covered in armor. Shortnose sturgeon are slow-growing and late-maturing, and they have been recorded to reach up to 4.5 feet in length and live 30 years or more.

Native American fishermen harvested shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon for their meat and eggs (roe) beginning some 4,000 years ago, and sturgeon are credited as the primary food source that saved the Jamestown settlers in 1607. In the mid-1800s, Atlantic and shortnose sturgeon began to support a thriving and profitable fishery for caviar, smoked meat, and oil. For the most part, historical landings records failed to differentiate between shortnose sturgeon and the larger Atlantic sturgeon, making it difficult to determine historical trends in abundance for populations of either species. By the late-1800s, sturgeon were being over-exploited. In 1890, over 7 million pounds of sturgeon were caught in 1 year alone. In 1920, only 23,000 pounds of sturgeon were caught.

Although shortnose sturgeon are no longer fished, threats remain that continue to affect recovery efforts. Bycatch in commercial fisheries and increased industrial uses of the nation’s large coastal rivers during the 20th century (e.g., hydropower, nuclear power, treated sewage disposal) became the primary barriers to shortnose sturgeon recovery.

Today, the shortnose sturgeon is in danger of extinction throughout its range and is listed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. The primary threats to this species are habitat degradation, water pollution, dredging, water withdrawals, fisheries bycatch, and habitat impediments (e.g., dams).

NOAA Fisheries and its partners are dedicated to conserving and rebuilding shortnose sturgeon populations along the East Coast. We use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and recover these endangered fish. Working closely with our partners, we develop regulations and management plans that preserve and restore sturgeon habitat, monitor bycatch, and promote population recovery.

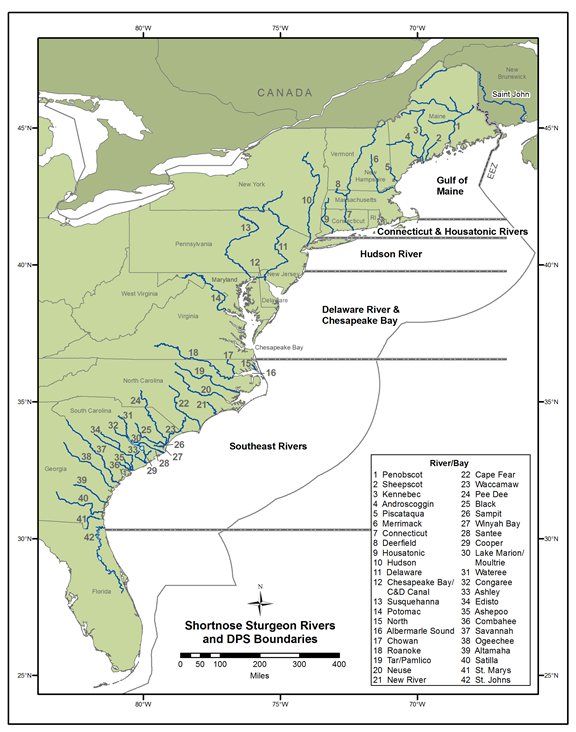

Distribution

Historically, shortnose sturgeon were found in the coastal rivers along the East Coast of North America—from the Saint John River in New Brunswick, Canada, to the St. Johns River in Florida, and perhaps as far south as the Indian River in Florida. Currently, shortnose sturgeon can be found in 41 bays and rivers along the East Coast, but their distribution across this range is broken up, with a large gap of about 250 miles separating the northern and mid-Atlantic metapopulations from the southern metapopulation. (A metapopulation is a group of separate but interacting populations such that there is gene flow occurring among the populations.) Because of this distance between the shortnose sturgeon in mid-Atlantic/northern metapopulations and the southern metapopulation, adults from the two regions may never meet to breed.

In the southern metapopulation, shortnose sturgeon are currently found in the Great Pee Dee, Waccamaw, Edisto, Cooper, Altamaha, Ogeechee, and Savannah rivers. They may also be found in the Black, Sampit, Ashley, Santee, Roanoke, and Cape Fear rivers, as well as Albemarle Sound and Pamlico Sound. Shortnose sturgeon used to be considered extinct in the Satilla, St. Marys, and the St. Johns rivers, but were recently found again in both the Satilla and St. Marys rivers. A single specimen was found in the St. Johns River by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission during extensive sampling of the river in 2002 and 2003; subsequent sampling by a different group in 2014 and 2015 found no shortnose sturgeon.

In the northern and mid-Atlantic metapopulations, shortnose sturgeon are currently found in the Saint John (Canada), Penobscot, Kennebec, Androscoggin, Piscataqua, Merrimack, Connecticut, Hudson, Delaware, and Potomac rivers. They have also been frequently spotted opportunistically foraging and transiting in the St. George, Medomak, Damariscotta, Sheepscot, Saco, Deerfield, East, and Susquehanna rivers. On rare occasions, they have been seen in the Narraguagus, Presumpscot, Westfield, Housatonic, Schuylkill, Rappahannock, and James rivers.

There are also two dam-locked populations of shortnose sturgeon that were trapped upstream of dams upon completion of their construction. Populations can be found above the Holyoke Dam on the Connecticut River. In South Carolina, shortnose sturgeon are also trapped in Lake Moultrie and Lake Marion above the dams on the Santee-Cooper river system (i.e., Pinopolis, Wilson, and St. Stephens dams). This population also uses the Congaree and Wateree rivers.

Population Status

The historical range of shortnose sturgeon included major estuaries (areas where rivers meet the sea) and river systems from Canada to Florida. No estimate of the historical population size of shortnose sturgeon is available. While shortnose sturgeon were rarely the target of a commercial fishery, they were often taken incidentally in the commercial fishery for Atlantic sturgeon. In the 1950s, sturgeon fisheries declined on the East Coast, which resulted in a lack of records of shortnose sturgeon. This led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that this species had been eliminated from the rivers in its historical range (except the Hudson River) and was in danger of extinction because of overharvest, both directly and incidentally, and other factors (e.g., pollution).

Currently, shortnose sturgeon are found in 41 rivers and bays along the East Coast, spawning in 19 of those rivers and comprising three “metapopulations,” or groups of interacting populations. These three metapopulations include the Carolinian Province (southern metapopulation), Virginian Province (mid-Atlantic metapopulation), and Acadian Province (northern metapopulation).

Learn more about the population status of the different metapopulations

Appearance

Shortnose sturgeon can grow to approximately 4.5 feet long and weigh up to 60 pounds. They are yellowish-brown and generally have a black head, back, and sides. Their bellies are white to yellow. They have five major rows of scutes (external, bony plates) along the length of their body and a protruding snout with four barbels (fleshy, whisker-like projections).

Shortnose sturgeon are similar in appearance to Atlantic sturgeon, but can be distinguished by their smaller size, larger mouth, smaller snout shape, and tail scute pattern.

Behavior and Diet

Spawning adults generally migrate upriver in spring, from January to April in the South, April to May in the Mid-Atlantic, and May to June in Canadian waters. After spawning, the adults typically move quickly back downstream to the lower river and estuaries. In most rivers, juveniles and adults show similar patterns of habitat use. For example, in the Southeast, juveniles make seasonal migrations like adults, moving upriver into relatively freshwater during warmer months where they shelter in deep holes, before returning to the fresh/saltwater interface when temperatures cool.

Shortnose sturgeon use their four barbels to search for food in the sandy, muddy bottom of rivers. They use a vacuum-like mouth to suck up a variety of prey from the substrate, typically invertebrates such as insects, crustaceans, worms, and mollusks.

Where They Live

Historically, shortnose sturgeon were found in the coastal rivers along the East Coast of North America from the Saint John River, New Brunswick, Canada, to the St. Johns River, Florida, and perhaps as far south as the Indian River in Florida. Currently, shortnose sturgeon occur in 41 bays and rivers along the East Coast, reproducing in 19 of them.

For the most part, shortnose sturgeon are amphidromous fish—meaning they are born in freshwater, then live in their birth (natal) river, make short feeding or migratory trips into salt water, and then return to freshwater to feed and escape predation. All sturgeon, including shortnose sturgeon, spawn in freshwater.

World map providing approximate representation of the shortnose sturgeon range.

World map providing approximate representation of the shortnose sturgeon range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Lifespan is correlated with how far north or south shortnose sturgeon live, with adults reaching up to 60 years in Canada, but likely only 10 to 20 years in the Southeast. Southern populations tend to grow faster and reach sexual maturity at an earlier age than other populations. For example, shortnose sturgeon mature in South Carolina and Georgia rivers around 2 to 5 years of age, in the Hudson River at 7 to 10 years, and in the Saint John River (Canada) at 12 to 18 years.

Male shortnose sturgeon usually spawn every 1 to 2 years once they mature, while females typically spawn every 3 to 5 years. The number of eggs females can produce is correlated with age and body size and ranges from 30,000 to 200,000 per year.

Threats

The most significant threats to the species are dams that block access to spawning areas or lower parts of rivers, poor water quality, dredging, water withdrawals from rivers, and unintended catch in some commercial fisheries.

Habitat Impediments

Locks and dams on the Cape Fear River, North Carolina; Santee-Cooper River, South Carolina; Savannah River, South Carolina/Georgia; and the Connecticut River impede access to upstream spawning habitat. The dams on the Santee-Cooper system also prevent the dam-locked population of shortnose sturgeon from traveling downstream, below the dams, to areas with better food sources.

For the past several years, NOAA Fisheries has been working with Holyoke Gas and Electric to improve fish passage on the Holyoke Dam on the Connecticut River. In 2017, the station opened a modified fishway, which consists of two “lifts” that carry migrating fish up and over the dam. For the first time in 20 years, shortnose sturgeon passed upstream of the dam. Prior to this effort, from 1996 to 2015, the greatest number of shortnose sturgeon passed by the lift was 16 in 1996. Since the modified fishway became operational, the number of shortnose sturgeon passing upstream at the lift has increased. From 2016-2019, the number of shortnose sturgeon passed at the dam ranged from 20 (2019) to 94 (2016).

Habitat Degradation

Habitats can be altered, degraded, or destroyed because of various human activities, such as dredging, damming, groundwater pumping. Industrialization and development has also impacted water quality through introduction of nutrients and other contaminants.

Fisheries Interactions and Bycatch

Fishermen may accidentally capture shortnose sturgeon while trying to catch something else. This is called bycatch. Shortnose sturgeon are primarily bycaught in gillnet fisheries. Shortnose sturgeon have also been captured in pound nets, fyke/hoop nets, catfish pots, shrimp trawls, and even recreational hooks and lines.

The prevalence and likelihood of bycatch varies by time of year. Time of year also affects the life stages that are caught and the likelihood of the sturgeon’s survival, as (survival is more likely in colder water.. Fisheries conducted within rivers and estuaries may intercept any life stage, while fisheries conducted in nearshore and ocean areas are more likely to capture migrating adults. The likelihood that an accidentally caught shortnose sturgeon will die in a gillnet appears to be related to water quality, how the net is set, and how long the net is left before being tended. Overall, gillnets not tethered to anything (“drift gillnets”) have lower capture rates than those attached to the bottom. The longer a net is in the water the greater the chance a captured shortnose sturgeon will die, and death is more likely when the water is warm.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Actinopterygii | Order | Acipenseriformes | Family | Acipenseridae | Genus | Acipenser | Species | brevirostrum |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/25/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

We are committed to the protection and recovery of shortnose sturgeon by implementing various conservation, management, and enforcement measures. Our work includes:

- Preserving existing habitats

- Improving existing habitat and restoring access to historical habitat (e.g., dam removals)

- Establishing benthic fish passage at dams that have not been removed

- Monitoring bycatch and stock recovery

- Educating the public

Science

We conduct research or work with research partners to gain understanding of the biology, behavior, and ecology of shortnose sturgeon. These research results are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this imperiled fish species. Our work includes:

- Collecting population information

- Tracking individuals over time to monitor important behaviors

- Studying genetic relationships among individuals and populations

- Studying migratory pathways and source/sink dynamics

How You Can Help

Know the Law Before You Fish

It is illegal to fish for, catch, or keep sturgeon—including Atlantic, Shortnose, and Gulf. If you accidently hook a sturgeon, be prepared to catch and release with care.

Report a Stranded, Injured, or Dead Sturgeon

If you find a stranded, injured, or dead sturgeon, please report it to NOAA Fisheries at (978) 281-9328 or in the Southeast at (844) STURG-911 or (844) 788-7491, or send us an email at noaa.sturg911@noaa.gov.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Learn About Bycatch

One of the main threats to marine animals is entanglement in fishing gear, especially gillnets. Fishermen sometimes catch and discard animals they do not want, cannot sell, or are not allowed to keep. This is collectively known as bycatch.

Featured News

A coho salmon swims up the Sol Duc river on the Olympic Peninsula. Credit: Adobe Stock.

A coho salmon swims up the Sol Duc river on the Olympic Peninsula. Credit: Adobe Stock.

Eric catches an American eel for an educational event about migratory fish. (Photo: Samuel Coulbourn)

Eric catches an American eel for an educational event about migratory fish. (Photo: Samuel Coulbourn)

Southern Resident killer whale swimming with calf. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Southern Resident killer whale swimming with calf. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Recommended 2024 Species Recovery Grants Projects

Populations

The historical range of shortnose sturgeon included major estuaries and river systems from Canada to Florida. Currently, shortnose sturgeon are found in 41 rivers and bays along the East Coast. They comprise three “metapopulations,” or genetically similar groups, suggesting that more interbreeding occurs in rivers within these metapopulations rather than between them. These three metapopulations include:

- Carolinian Province (Southern metapopulation)

- Virginian Province (Mid-Atlantic metapopulation)

- Acadian Province (Northern metapopulation).

Each group constitutes important genetic diversity.

Shortnose sturgeon metapopulations. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Southern Metapopulation

The current status of shortnose sturgeon in the Southern Metapopulation depends on the river in which they live. Overall, populations within the Southern Metapopulation are relatively small compared to their northern counterparts. The Altamaha and Savannah rivers support the largest known shortnose sturgeon population in the Southeast. Total population estimates for the Altamaha River ranged from 468 fish (1993) to over 5,550 fish (2006), with estimates in the Savannah River ranging from 1,390 (2009) to 2,432 (2013).

Abundance estimates indicate the shortnose sturgeon population in the Ogeechee River is considerably smaller, with the highest estimate of the total population being 404 individuals (2007). Since 2007, sampling in this river suggests the population might be declining.

Spawning is also occurring in the Cooper, Congaree, and Yadkin-Pee Dee rivers. While active spawning is occurring in South Carolina’s Winyah Bay complex (Black, Sampit, Yadkin-Pee Dee, and Waccamaw rivers), the population status there is unknown. The most recent estimate for the Cooper River suggests a population of approximately 220 spawning adults. The status of the other riverine populations within the Southern Metapopulation is currently unknown.

Northern and Mid-Atlantic Metapopulations

The population estimates of shortnose sturgeon in the northern and mid-Atlantic metapopulations vary by river. The Hudson, Saint John (New Brunswick, Canada), and Delaware rivers support the largest known shortnose sturgeon populations in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. For the Hudson River, the total population estimates ranged from 5,837 fish (1979) to 80,026 (1995). In the Saint John River, the total adult population was estimated at 18,000 adults (1970s), but the confidence intervals are wide (7,200 to 28,800 adults), suggesting uncertainty. Estimates in the Delaware River are at approximately 12,047 adults (2006). Available data suggests that the Hudson population has increased over the past several decades, and the Saint John and Delaware populations may be stable.

One of the smaller populations in these regions is in the Merrimack River. The highest estimate of adults was 2,000 individuals (2009). This is significantly higher than the estimate 20 years before (32 adults), but telemetry studies have shown that most of these adults return to spawn in the Kennebec River.

Spawning also occurs in the Saint John (Canada), Androscoggin, Kennebec, and Connecticut rivers, and it may occur in the Potomac River. The most recent population estimate for the Saint John River was 18,000 adults (1979). The Kennebec System has an estimated population size of 9,488 adults (2003). For the Connecticut River, the downstream segment (below Holyoke Dam) was estimated to have 1,600 adults (2004), and the upstream segment (above Holyoke Dam) was estimated to have 328 adults (2012). The population estimate for the Potomac River is currently unknown because few shortnose sturgeon have been captured there since they were listed under the Endangered Species Act. Telemetry studies suggest these fish might have moved through the Chesapeake Delaware Canal and spawned in the Delaware River.

More Information

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/25/2025

Management Overview

The shortnose sturgeon is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Additionally, the shortnose sturgeon is listed under:

- Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Action

In 1998, NOAA Fisheries approved the shortnose sturgeon recovery plan. Drafted by a team of federal, state, and academic scientists and resource managers, the plan identifies actions that would promote the recovery and delisting of shortnose sturgeon. Specifically, the recovery plan seeks to recover shortnose sturgeon populations to levels of abundance at which the species would no longer require protection under the ESA. Specific recovery activities are organized under four broad recovery actions:

- Develop criteria for assessing the status of shortnose sturgeon populations

- Protect shortnose sturgeon and their habitats

- Rehabilitate shortnose sturgeon populations and habitats

- Implement recovery tasks

Implementation

NOAA Fisheries has completed some of the actions described in the 1998 recovery plan and continues to implement others. These actions range from improving our understanding of shortnose sturgeon genetics, to reducing bycatch in fisheries by researching ways bycatch occurs and what factors make interactions more deadly. We are also working, along with our partners, to reduce man-made impacts, for instance by determining how pollution affects shortnose sturgeon and investigating ways for shortnose sturgeon to get around man-made barriers. Along with our partners, we are also restoring degraded shortnose sturgeon habitat, for instance by removing barriers to their migration.

Species Recovery Contacts

Southeast Region

Andrew Herndon, Species Recovery Coordinator

Greater Atlantic Region

Lynn Lankshear, Species Recovery Coordinator

Conservation Efforts

Restoring Habitat and Fish Passage

Sturgeon and other migrating fish, such as salmon, shad, and alewives, need access to freshwater habitat for spawning and rearing. In some cases, shortnose sturgeon need to swim long distances to reach their destination, but man-made barriers such as dams may block them from completing their journey. These barriers have had serious impacts on shortnose sturgeon spawning runs, particularly in the Southeast, and their habitats along the entire East Coast. Removing certain outdated dams or providing ways for fish to get around those dams can greatly improve shortnose sturgeon access to their historical habitats. NOAA Fisheries works with conservation organizations, hydroelectric power companies, states, tribes, and citizens to evaluate barriers—big and small—to fish passage. Most barriers have the same general impact on fish (blocking migrations), but each requires a specific set of conservation actions.

Learn more about improving fish passage

Providing Captive Breeding Programs

Some shortnose sturgeon are bred and held in captivity at research facilities in accordance with specific permits. These captive-bred animals can provide important insight into the physical, chemical, and biological parameters necessary for the optimal growth, survival, and reproduction of shortnose sturgeon in the wild. Some captive-bred animals are also used in permanent educational displays that promote public awareness of the plight of the species.

Educating the Public

One of the best ways to help save this amazing species is through outreach. Our biologists work with students and teachers to share information about the movements, behavior, and threats to Atlantic and shortnose sturgeons along the East Coast. The SCUTES program—Students Collaborating to Undertake Tracking Efforts for Sturgeon—provides lesson plans, educational kits, and an opportunity for classrooms to adopt a tagged sturgeon.

Learn more about the SCUTES program

Cooperating Internationally

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) protects shortnose sturgeon and other sturgeons by regulating international trade in listed species of plants and animals.

Regulatory History

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service originally listed shortnose sturgeon as an endangered species on March 11, 1967, under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, the precursor to the ESA. NOAA Fisheries assumed jurisdiction for shortnose sturgeon from the U.S. FWS under a 1974 government reorganization plan. The ESA was enacted in 1973 and all species that were listed as endangered in the 1969 Endangered Species Conservation Act were deemed endangered under the ESA. Shortnose sturgeon currently remain listed as endangered throughout their range along the U.S. East Coast.

Although the original listing notice did not cite reasons for listing shortnose sturgeon, a 1973 U.S. Department of Interior resource publication stated that the species was “in peril... gone in most of the rivers of its former range [but] probably not as yet extinct." Pollution and overfishing, including bycatch in the shad fishery, were listed as principal reasons for the species' decline.

Key Actions and Documents

Incidental Take Permit to Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc

Incidental Take Permit to Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Incidental Take Permit to North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries (Sea Turtles and Sturgeon)

- Notice; Issuance of Permit (89 FR 82573, 10/11/2024)

- Notice of Availability - Draft Environmental Assessment (88 FR 54303, 08/10/202…

- Correction to Receipt of Application (88 FR 859, 01/05/2023)

- Receipt of application (87 FR 78659, 12/22/2022)

Incidental Take Permit to Midwest Biodiversity Institute

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/25/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of shortnose sturgeon. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for endangered shortnose sturgeon populations.

Tagging and Tracking

Scientists use various tagging techniques to learn about the migration patterns of shortnose sturgeon and identify important juvenile habitats. Commonly used tags are T-bar, passive integrated transponder, radio, satellite, pop off, and acoustic tags (tags detected using sound). T-bar, dart, and PIT tags allow other researchers to identify an individual fish when it is captured. Acoustic and satellite telemetry tags (tags using radios to locate) let researchers learn where shortnose sturgeon travel, at what depths, and at what speeds.

Genetics

Shortnose sturgeon researchers take small fin clips from sturgeon they catch to better understand the genetic composition of the populations. In 2010, geneticists determined that all shortnose sturgeon can be identified as belonging to one of three regional groups or metapopulations. Shortnose sturgeon that are accidentally captured or killed can be identified to one of these metapopulations using information in their DNA (genotype). By comparing the differences in the DNA of animals within a population, researchers can work backward to determine how many genetically different spawning adults would be needed to create that amount of genetic difference. All this information helps us learn more about where animals come from and their family history. NOAA Fisheries, in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey, has been maintaining stored tissue and DNA samples and records of shortnose sturgeon, as well as Atlantic sturgeon.

Side Scan Sonar

Recently, researchers and managers have used a type of sonar known as side scan sonar to estimate the number of sturgeon that appear on the sonar image. While promising, this approach is still being perfected. Most rivers are wide enough that multiple passes are needed to cover the entire width. Likewise, most rivers are so long that sampling the entire river is not possible. Therefore, an equation to account for unsampled areas and fish counted multiple times is needed to correct the estimate. Additionally because shortnose sturgeon are smaller than other sturgeon species, their images can sometimes be hard to differentiate from large gar, catfish, or juvenile Atlantic sturgeon. As a result, researchers and managers will need to refine this approach to make sure they accurately detect shortnose sturgeon.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/25/2025

Documents

What Happens After Dam Removals - Resources

What Happens After Dam Removals: Collaborative research on Penobscot dam removals show initial…

Biological Assessment of Shortnose Sturgeon Acipenser Brevirostrum

A 2010 5-year status review which includes the most current complete biological assessment of…

Biological Opinion on the Issuance of Permit No. 14604 for Research on Shortnose Sturgeon in the Delaware River

NOAA Fisheries' biological opinion evaluating proposed scientific research of shortnose sturgeon in…

Biological Opinion on the Issuance of Permit No. 14754 for Research on Hatchery Produced Shortnose Sturgeon

NOAA Fisheries' biological opinion of the proposed research of hatchery-produced shortnose sturgeon…

Data & Maps

Recovery Action Database

Tracks the implementation of recovery actions from Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans.

Research

Fisheries Ecology in the Northeast

We study the relationship between marine life and their environment to support sustainable wild and farmed fisheries on the Northeast shelf, creating opportunities and benefits for the economy and ecosystem.

Outreach & Education

SCUTES: Students Collaborating to Undertake Tracking Efforts for Sturgeon

Lesson plans to help you instruct and inform your students about Atlantic and shortnose sturgeon.

Report a Sturgeon Sign

This sign is often posted near boat ramps, piers, docks, marinas, and waterfront parks. Signs may…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 04/25/2025