Much of the seafloor in the Gulf of Alaska is covered in mud and sand. While most corals and sponges do not occur in large numbers in these habitats because the soft sediment can clog their feeding processes, or does not provide a place for attachment, it doesn’t mean these areas are lifeless. Tunnels, boroughs and all sorts of fish and invertebrates can be found in these habitats, and they are an important part of the Gulf of Alaska ecosystem.

While most corals and sponges do not occur in large numbers in these habitats because the soft sediment can clog their feeding processes, or does not provide a place for attachment, it doesn’t mean these areas are lifeless.

At another site located near the U.S./Canada border we came across extensive aggregations of sponges growing on underwater rock cliffs and ledges.

Most of these sponges were a type of Hexactinellids, or “glass sponge”, named for the internal silica skeleton, that elevates the sponge above the seabed so it can feed, grow, and reproduce.

[Glass sponges] provide structural habitat for new generations of glass sponge. They also provide a refuge and foraging ground for other species. They filter vast quantities of seawater for the bacteria that nourish them and expel nutrients.

Dense aggregations of glass sponges can transform a relatively homogenous reef into a complex and unique marine ecosystem. They provide structural habitat for new generations of glass sponge. They also provide a refuge and foraging ground for other species. They filter vast quantities of seawater for the bacteria that nourish them and expel nutrients. When upwelled, this contributes to photosynthesis.

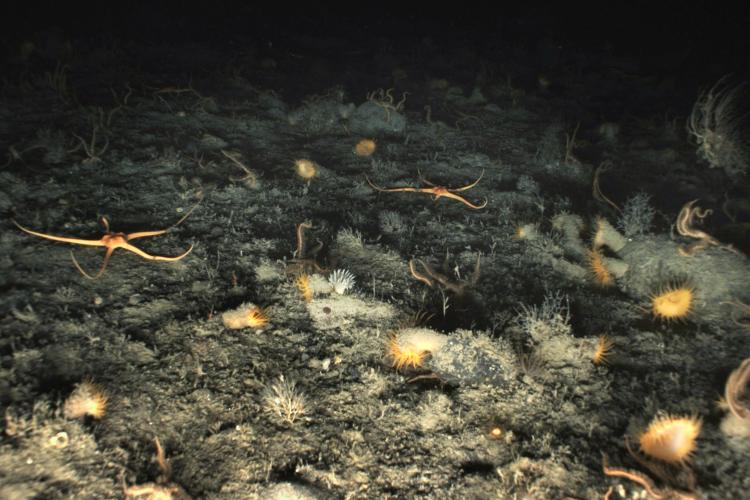

Sometimes we come across the unexpected. At one station near the mouth of Chatham Strait we came across a vast pile of logs covered by hydroids (moss like animals), brittle stars, and other invertebrates.

How these logs came to rest here we don’t know. It is just one of the unexpected surprises we have encountered on this expedition.

The region we are working in is surrounded by the Tongass National Forest. This is a vast forest that has a long history of logging. Logs were often transported via water to sawmills. How these logs came to rest here we don’t know. It is just one of the unexpected surprises we have encountered on this expedition.

Finally, on another dive as the drop camera descended we came across a halibut swimming in the water column many feet above the bottom. When the camera landed on the seafloor, about thirty more halibut were observed.

Normally, we may see one or two halibut per dive, so this was an unusual observation.

Normally, we may see one or two halibut per dive, so this was an unusual observation. What made it even more unusual is that in a nearby dive at the same depth and habitat, we did not see any halibut. We speculate the difference was due to a school of baitfish, likely Pacific herring. These fish were observed on the ship’s sounder above where the halibut were spotted.