Toxoplasmosis and Its Effects on Hawaiʻi Marine Wildlife

NOAA is responsible for managing endangered species, including the Hawaiian monk seal. One of the greatest population threats is the infectious disease toxoplasmosis, a threat many people haven't heard about. Learn how you can help protect Hawaiian monk seals from toxoplasmosis.

Understanding Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is an infectious disease that can cause serious health problems for wildlife and humans. It is caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), which reproduces in the intestines of cats. Infectious eggs, known as oocysts, are released into the environment through cat feces. While other animals can carry the T. gondii parasite, the parasite can reproduce—and develop infectious eggs—only in cats. Ingesting food or water contaminated by infectious eggs can cause toxoplasmosis in humans and animals.

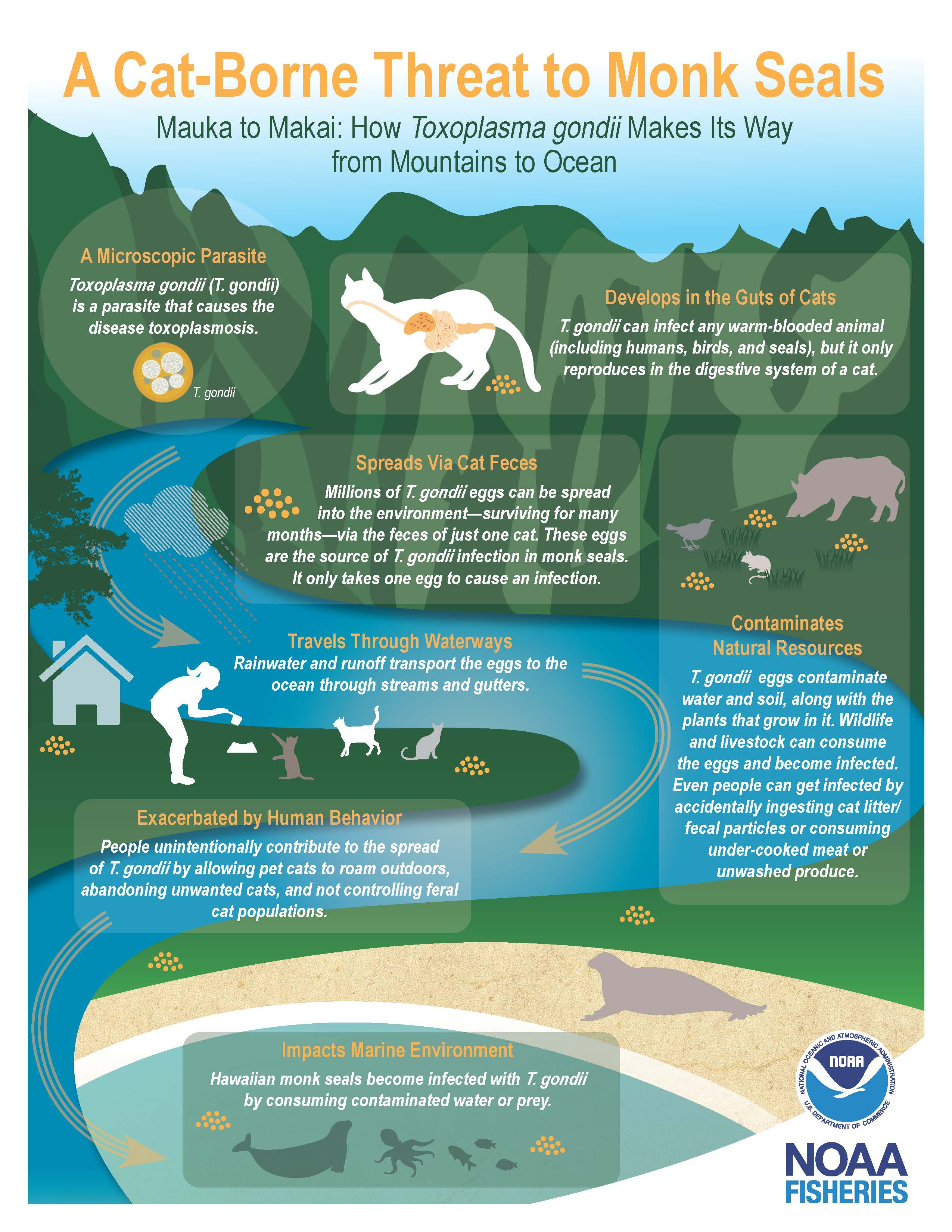

Infographic: A Cat-Borne Threat to Monk Seals

Toxoplasmosis and Hawaiian Monk Seals

Why does NOAA Fisheries care about Toxoplasmosis?

NOAA Fisheries is responsible for conserving and protecting the endangered Hawaiian monk seal (Neomonachus schauinslandi). The population overall had been declining for six decades. But, it is currently experiencing an upward trend, due in part to recovery efforts. The Hawaiian monk seal is one of NOAA Fisheries' Species in the Spotlight. This initiative is a concerted, agency-wide effort launched in 2015 to spotlight and save the most highly at-risk marine species.

Toxoplasmosis poses a significant threat to monk seals. It may cause the loss of a fetus and often leads to inflammation and dysfunction of internal organs, which can lead to debilitation and death. Infected monk seals may also display behavioral changes, such as floating listlessly (logging), which often happens before death. Logging is generally understood to be a sign of pain from the inflammation associated with an infection or injury.

All monk seals diagnosed with toxoplasmosis have died from the disease, even with treatment. There is currently no successful treatment or vaccine for toxoplasmosis, either in the host cats or in other animals that become infected with the disease. Preventing initial exposure and raising awareness of the disease are essential to controlling the spread of toxoplasmosis. Hawaiian monk seals are an important part of the coral reef ecosystem and act as sentinels to ocean health.

Learn more about Hawaiian monk seals

How does toxoplasmosis compare to other threats to the Hawaiian monk seal?

The three leading threats to Hawaiian monk seals in the main Hawaiian Islands are all tied back to people:

- Intentional killings, including ballistic and blunt-force trauma

- Fisheries interactions with nearshore recreational and subsistence fisheries (such as hookings and gill net entanglements)

- Toxoplasmosis

These threats are not just for adult seals. They also affect weaned pups, juveniles, and subadults, preventing seals from reaching adulthood and hindering the growth of the population. Worse yet, toxoplasmosis is disproportionately affecting females, which means an even greater reproductive loss for an already slow-reproducing species.

Although resources are in place to help reduce intentional killings and entanglements, not many people know about the dangers of toxoplasmosis affecting marine mammals. NOAA hopes to raise awareness about the effects of toxoplasmosis and highlight actions that can be done to reduce its impact on wildlife.

How many Hawaiian monk seals have been killed by toxoplasmosis?

As of 2023, there have been 15 confirmed cases of seals dying due to toxoplasmosis in Hawai‘i. There have been two clusters of deaths in Hawaiian monk seals in recent years. Three seals died within the span of one week in May 2018 and two seals stranded with toxoplasmosis from December 2019 to January 2020, with one succumbing to the disease after months of treatment. The actual number of toxoplasmosis-induced deaths is likely to be higher because some monk seal carcasses are not found, unable to be brought in for examination, or are too decomposed to determine the cause of death.

It is important to note that more female seals are killed by toxoplasmosis than males. When we lose even one female seal, we also lose their reproductive potential for future generations. For example, the family tree of Hawaiian monk seal R006 (“Mama Eve”) shows 85 seals resulting from her single lineage (her pups, grandpups, great grandpups, and great-great grandpups). The loss of just one female could mean a loss of almost 100 seals to the population over time.

Although 15 confirmed cases of toxoplasmosis may not seem like a large number, there are only approximately 380 seals in the main Hawaiian Islands. Because toxoplasmosis is one of the leading causes of monk seal deaths, managing it is a top priority. The recovery of the species, especially in the main Hawaiian islands, will rely on human behavior change and reducing the risks from cats on the landscape.

A potentially life-saving action is to call our Marine Wildlife Hotline at (888) 256-9840. This is the most effective and fastest way to get information to our teams. Calling the hotline to report a seal and informing us about logging concerns allows us to evaluate the seal’s condition as soon as possible. Logging is not necessarily a cause for alarm, and some seals may exhibit this behavior for short periods of time even when they appear healthy. However, it is often an indicator of injury or other health problems like toxoplasmosis.

How do monk seals contract toxoplasmosis?

T. gondii sexually reproduces only in the digestive tract of cats, producing infectious eggs that are shed into the environment through cat feces. These eggs can be transported from anywhere on the landscape to the ocean by watershed runoff. This exposes marine mammals to the infectious eggs either through consuming infected prey or direct exposure to eggs in the water. These eggs are hardy and can survive in water and soil for 24 months, possibly longer. Cats are the definitive hosts of T. gondii that can infect monk seals with toxoplasmosis (via oocysts or infected prey).

Can other animals besides cats spread toxoplasmosis?

Only members of the family Felidae (domestic cats and their relatives) can spread toxoplasmosis because the parasite reproduces solely within cats’ digestive systems. Cats can shed 3 to 800 million eggs into the environment through their feces in the weeks after they are initially infected. It only takes the ingestion of a single egg to cause an infection.

Any cat has the potential to acquire the infection and spread infectious eggs. The likelihood of this happening in indoor-only pet cats is low because they have limited opportunities to contract or spread the infection. But outdoor domestic cats (pet cats allowed to roam outdoors and cats living outdoors on their own) can spread infectious eggs.

Besides monk seals, what other animals can be infected with toxoplasmosis?

Any warm-blooded animal, including humans, can be infected with toxoplasmosis. While we present facts and figures primarily pertaining to Hawaiʻi, it is important to keep in mind that toxoplasmosis is a global issue. In Hawaiʻi, toxoplasmosis also poses a threat to the Hawaiian spinner dolphin and several species of native birds, including the Hawaiian goose (nēnē) and the Hawaiian crow (ʻalalā).

There have been confirmed cases of toxoplasmosis causing death in spinner dolphins. But with a carcass recovery rate of only 5 percent, the number of spinner dolphin deaths due to toxoplasmosis could be closer to 60 over the past 30 years. The rate of exposure and the indirect effects caused by toxoplasmosis to spinner dolphins remains unknown. Hawaiian spinner dolphins and other nearshore species are likely at increased risk of mortality from toxoplasmosis as T. gondii eggs are carried to nearshore waters via estuaries, sewage systems, stormwater drainage, and surface water runoff.

Toxoplasmosis is the most common infectious disease encountered by the nēnē goose and causes approximately 4 percent of nēnē mortalities. The disease may also have non-lethal or behavioral effects that could make the nēnē more susceptible to death from other causes. Toxoplasmosis had a large impact on the ʻalalā and seems to have been at least partially responsible for initial failures to re-establish wild ʻalalā populations. In 1998, seven out of 11 released crows died over a 4-month period. The remaining birds were recaptured, with one recaptured crow and four carcasses exhibiting infection with T. gondii parasite. The ʻalalā is now extinct in the wild and survives only in captivity.

Beyond Hawai‘i, toxoplasmosis impacts other threatened and endangered species. In California, this disease has been shown to affect sea otters and contributes to one of the threats to recovery for the California sea otter population.

Free-Roaming Cats in Hawaiʻi

With the large population of cats on the landscape in Hawai‘i, cats continue spreading infectious eggs into the watershed. Free-roaming cats also cause harm to other native species, including birds and sea turtles. There are an estimated 300,000 free-roaming cats on the island of Oʻahu alone. This includes domestic cats that are feral, abandoned, lost to their owners, or live indoors but are allowed outside.

Trap, neuter, and return/release (TNR) is being used by many animal welfare organizations. Research has shown that 70 to 90 percent of the cats in an outdoor cat colony must be sterilized, and no new cats must join the colony, for the population to begin to decline because of TNR efforts. These conditions are difficult to achieve in most situations because cat colonies aren’t often isolated. Cats that live indoors but are let outdoors or are lost, abandoned from another colony, or born to an outdoor cat regularly contribute to colony growth.

TNR does not stop the spread of toxoplasmosis, or reduce predation on native bird species and sea turtles. But, sterilization of cats in fully closed colonies, such as sanctuaries, could help reduce those populations.

More practically, Hawai‘i needs a multi-pronged approach that includes promoting responsible pet ownership, curtailing the number of animals abandoned by residents, and reducing the number of at-large cats on the landscape.

Help Care for Cats, Wildlife, and Hawaiʻi

The single most important thing people can do to help prevent toxoplasmosis from spreading in the environment is to make sure pets are spayed or neutered and kept indoors, or at least confined. This is beneficial for native wildlife and for cats as well. Indoor cats live longer and are at lower risk for illness and injury.

The transition from outdoor cat to indoor cat can be challenging, but there are many ways to successfully keep your cat indoors. Check out the Pono Cat Parent resources to learn more.

Ultimately, keeping your cat indoors is highly beneficial:

- Your cat will likely live longer

- You will be keeping your family and your pet safe from harmful diseases and parasites

- You will be helping reduce the free-roaming cat population in the islands

- You will help ensure the conservation of many species in Hawaiߵi, including some only found in the Hawaiian Islands

More Resources About Toxoplasmosis

More Information

More Information

- Shining a Light on Toxoplasmosis in Hawaiʻi

- Disease Causes Three Hawaiian Monk Seal Deaths

- Taking a Deep Dive into a Land-based Threat to Hawaiian Monk Seals

- The Toll of Toxoplasmosis: Protozoal Disease Has Now Claimed the Lives of 12 Monk Seals and Left Another Fighting to Survive

- Monk Seal RO28 Brought in for Evaluation and Observation

- Pohaku Passes Away After Fight Against Toxoplasmosis

- RO28 (Pohaku) Chronicles Podcast

- Further Analysis Reveals Toxoplasmosis as Cause of Death for RK40