Olive Ridley Turtle

Lepidochelys olivacea

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Olive ridley sea turtle on beach. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

Olive ridley sea turtle on beach. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

Olive ridley sea turtle on beach. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Olive ridley sea turtle on beach. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

Olive ridley sea turtle on beach. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

Olive ridley sea turtle on beach. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

The olive ridley gets its name from the olive green color of its heart-shaped shell. This species is among the smallest, but the most widespread and abundant of the world’s sea turtles. Olive ridleys have two nesting strategies, solitary or mass nesting (arribada). An arribada refers to the phenomenon of synchronized mass nesting of thousands, if not tens of thousands, of olive ridleys.

Olive ridleys are found throughout the world primarily in the tropical regions of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans. The number of olive ridleys is greatly reduced from historical estimates, which suggest that up to 10 million olive ridleys once roamed the Pacific Ocean. Today, just a handful of mass nesting (arribada) beaches account for the largest numbers of nesting females. Bycatch in fishing gear and the direct harvest of turtles and eggs are the most significant threats facing olive ridleys.

NOAA Fisheries and our partners are dedicated to protecting and recovering olive ridley populations worldwide. We use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and recover these threatened and endangered populations. We engage our international partners as we develop measures and recovery plans that foster the conservation and implement recovery of olive ridleys and their habitats. NOAA Fisheries also funds research, monitoring, and conservation projects to implement priorities outlined in recovery plans.

Population Status

Olive ridley turtles are found worldwide and listed under the Endangered Species Act. Their breeding colony populations on the Pacific Coast of Mexico are listed as endangered; all others are listed as threatened. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List, there has been between a 30 to 36 percent reduction in global population size over the last century. Although some nesting populations have increased in the past few years or are currently stable, the overall reduction in some populations is greater than the overall increase in others.

In the western Atlantic Ocean, although there has been an over 90 percent reduction in certain arribada nesting populations in Suriname since 1967, Brazil and French Guiana have seen increases in their non-arribada nesting population. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, Gabon currently hosts the largest olive ridley nesting population in the region with 1,000 to 5,000 breeding females per year.

In the Pacific, large nesting populations occur in Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. For example, an arribada nesting beach in La Escobilla, Mexico hosts an estimated 450,000 nesting female turtles, and the Pacific coast of Costa Rica supports an estimated 600,000 nesting olive ridleys between its two major arribada beaches, Nancite and Ostional.

In the Indian Ocean, three arribada beaches occur in Odisha, India (Gahirmatha, Devi River mouth, and Rushikulya) with an estimated +100,000 nests per year. More recently, a new mass nesting site was discovered in the Andaman Islands, India, with more than 5,000 nests reported in a season. Declines in solitary nesting of olive ridleys have been recorded in Bangladesh, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Pakistan. In particular, the number of nests in Terengganu, Malaysia, has declined from thousands of nests to just a few dozen per year. Fortunately, increased monitoring activities in Southeast Asia over the past decade have identified new nesting beaches in the Philippines and Indonesia.

The 2014 ESA 5-year review of the olive ridley sea turtle provides additional information on abundance and population trends for this species.

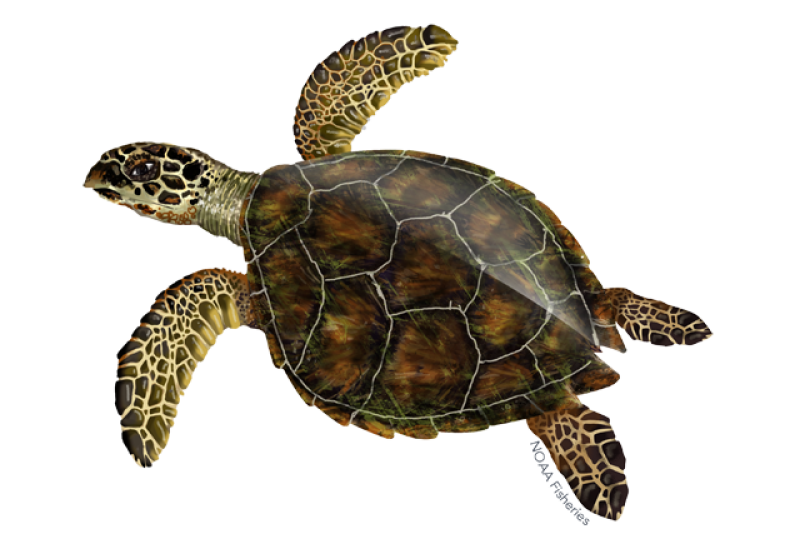

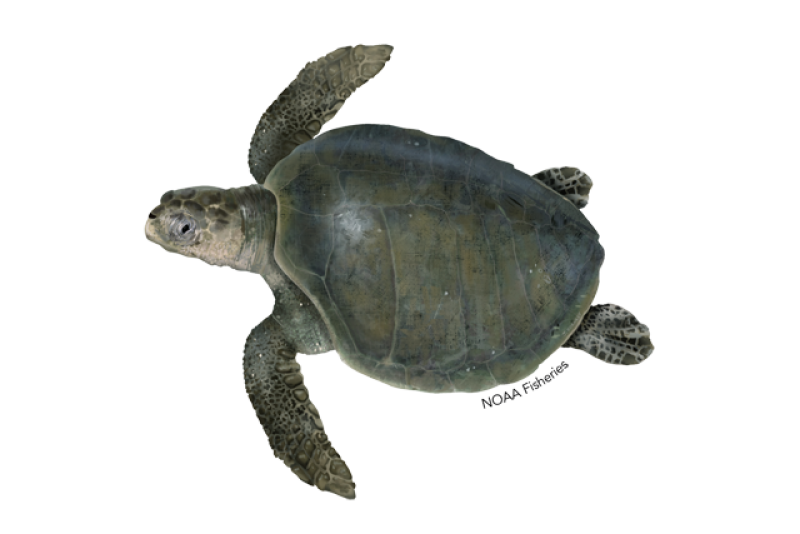

Appearance

Olive ridleys look very similar to Kemp’s ridley sea turtles. The two species are the smallest of all sea turtles. Olive ridley turtles are an olive/grayish-green with a heart-shaped carapace (top shell) having 5 to 9 pairs of lateral scutes. Each of the four flippers of an olive ridley has one or two claws. The size and form of the olive ridley varies from region to region, with the largest animals observed in West Africa.

Behavior and Diet

Olive ridley turtles, like all sea turtles, are marine reptiles and must come to the surface to breathe. Adult female sea turtles return to land to lay their eggs on sandy beaches—they are remarkable navigators and usually return to a beach in the general area where they hatched.

Arribada nesting is a behavior found only in the genus Lepidochelys which includes the Kemp's ridley and olive ridley sea turtles. Although other turtles have been documented nesting in groups, no other turtles (marine or land) have been observed nesting synchronously in such mass numbers. Solitary nesting also occurs extensively throughout this species' range, and nesting has been documented in approximately 40 countries worldwide. Arribada nesting, however, occurs on only a few beaches worldwide.

Olive ridleys often migrate great distances between feeding and breeding grounds. Using satellite tags, scientists have documented both male and female olive ridleys leaving the breeding and nesting grounds off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and migrating out to the deep waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Olive ridleys are omnivorous, meaning they feed on a wide variety of food items, including algae, crustaceans, tunicates, and mollusks. Olive ridleys can dive to depths of 500 feet to forage on benthic invertebrates (those that live on the bottom).

Where They Live

The olive ridley is mainly a pelagic (open ocean) sea turtle, observed by trans-Pacific ships over 2,400 miles from shore, but they are also known to inhabit coastal areas. Olive ridleys are globally distributed in the tropical regions of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. In the Atlantic Ocean, they are found along the coasts of West Africa and northern South America. In the Eastern Pacific, they occur from Southern California to Northern Chile.

World map providing approximate representation of the olive ridley's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the olive ridley's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

No one knows exactly how long olive ridleys live, but like other sea turtles, they likely live for decades. Olive ridleys reach maturity around 14 years of age at which point they display one of the most extraordinary behaviors in the natural world. Similar to Kemp’s ridleys, immense swarms of olive ridleys gather offshore of nesting beaches. Then, all at once, they come ashore and nest in what is known as an "arribada", meaning "arrival" in Spanish. During these arribadas, hundreds to thousands of females come ashore to lay their eggs in synchrony. At many nesting beaches, the nesting density is so high that previously laid egg clutches are dug up by other females while excavating the nest chamber to lay their own eggs.

There are many theories on what triggers an arribada, including offshore winds, lunar cycles, and the release of pheromones by females. However, scientists have yet to conclusively determine why exactly arribadas occur. Not all females nest during an arribada—some are solitary nesters while others employ a mixed nesting strategy. For example, a single female might nest during an arribada, as well as nest alone during the same nesting season.

Females nest every year, one to three times a season, laying clutches of approximately 100 eggs. When finished laying, most sea turtles cover their eggs with sand using their rear flippers to pack the sand firmly on top of their clutch. However, since the olive ridley is so small and relatively light, they do not have the power to use their rear flippers in this way—instead, they use their whole bodies, beating the sand down with their lower shells after covering the eggs. The sex of hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the sand during the second trimester of incubation. Once the turtles hatch out of their eggs and climb to the surface, the hatchlings make their way to the sea. Hatchlings orient seaward by moving away from the darkest silhouette of the landward dune or vegetation to crawl towards the brightest horizon. On developed beaches, this is toward the open horizon over the ocean.

Threats

Bycatch in Fishing Gear

A primary threat to olive ridleys is their unintended capture in fishing gear, which can result in drowning or cause injuries that lead to death or debilitation (for example, swallowing hooks or flipper entanglement). The term for this unintended capture is bycatch. Sea turtle bycatch is a worldwide problem. The primary types of gear that result in bycatch of olive ridleys include trawls, longlines, gillnets, and purse seines.

Direct Harvest of Turtles and Eggs

The principle cause of the worldwide decline of olive ridleys was long-term collection of eggs and mass killing of adult females on nesting beaches for meat. The arribada nesting behavior concentrates females and nests at the same time and in the same place, enabling the collection of an extraordinary number of nesting females and eggs for human consumption. Historically, egg collection for human consumption was a significant problem, but this threat has been diminished in some countries with bans on the killing of turtles and collection of eggs.

Loss and Degradation of Nesting Habitat

Coastal development and rising seas from changing environmental conditions are leading to the loss of nesting beach habitat for olive ridleys. Human-related changes associated with coastal development include beachfront lighting, shoreline armoring, and beach driving. Shoreline hardening or armoring (e.g., seawalls) can result in the complete loss of dry sand suitable for successful nesting. Artificial lighting on and near nesting beaches can deter nesting females from coming ashore to nest and can disorient hatchlings trying to find the sea after emerging from their nests.

Predation of Eggs and Hatchlings

The destruction and consumption of eggs and hatchlings by native and non-native beach predators (particularly feral pigs dogs, and cats, coyotes, coatis, birds, and crabs) can dramatically affect hatchling production and survival and is therefore a threat to olive ridley populations.

Vessel Strikes

Various types of watercraft can strike sea turtles when they are at or near the surface, resulting in injury or death. Vessel strikes are a threat to sea turtles near ports and waterways, and along developed coastlines throughout their range. High boat traffic areas such as marinas, boat ramps and inlets present a higher risk. Adult sea turtles, in particular nesting females, are more susceptible to vessel strikes when making reproductive migrations and while they are nearshore during the nesting season.

Ocean Pollution/Marine Debris

Increasing pollution of nearshore and offshore marine habitats threatens all sea turtles and degrades their habitats. Ingestion of marine debris is another threat to all species of sea turtles. Olive ridleys may ingest marine debris such as fishing line, balloons, plastic bags, plastic fragments, floating tar or oil, and other materials discarded by humans which they can mistake for food. They may also become entangled in marine debris, including lost or discarded fishing gear, which can lead to injury or death.

Changing Environmental Conditions

For all sea turtles, changing environmental conditions like higher sand temperatures can be lethal to eggs or alter the ratio of male and female hatchlings produced (due to temperature dependent sex determination). Rising seas and storm events change beach morphology and cause beach erosion, which may flood nests or wash them away. Changes in the temperature of the marine environment are likely to alter habitat suitability, as well as the abundance and distribution of food resources, leading to a shift in the migratory and foraging range and nesting season of olive ridleys.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Reptilia | Order | Testudines | Family | Cheloniidae | Genus | Lepidochelys | Species | olivacea |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 05/29/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

Since 1977, NOAA Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) have shared jurisdiction of sea turtles listed under the ESA. A Memorandum of Understanding outlines our specific roles: NOAA Fisheries leads the conservation and recovery of sea turtles in the marine environment, and the U.S. FWS leads conservation and recovery efforts for sea turtles and their nesting beaches.

We are committed to the protection and conservation of olive ridleys by:

- Working with partners to ensure compliance with national, state, and U.S. territory laws to protect sea turtles and their habitats.

- Cooperating with international partners to implement conservation measures supported by international treaties that protect sea turtles.

- Researching, developing, and implementing changes to fishing gear practices and/or fishing gear modifications (e.g., turtle excluder devices in trawl fisheries and using large circle hooks in longline fisheries), and implementing spatial or temporal closures to avoid or minimize bycatch.

- Protecting and monitoring olive ridleys in the marine environment and on nesting beaches.

- Conducting research on threats and developing conservation measures that reduce threats and promote recovery, and on the species biology and ecology to better inform conservation management strategies and to assess progress toward recovery.

- Conducting and supporting education and outreach efforts to the general public by raising awareness on threats to sea turtles, highlighting the importance of sea turtle conservation, and sharing ways people can help sea turtles.

- Working with partners to study and raise awareness about illegal sea turtle trade.

Science

We conduct various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of olive ridleys. The results of this research are used to evaluate population trends, inform conservation management strategies, and to assess progress toward recovery for this protected species. Our work includes:

- Monitoring populations through vessel-based or aerial surveys, nesting beach studies, satellite tracking, genetics, endocrinology, biomarker analysis, and mark-recapture (flipper tagging) studies.

- Studying foraging and reproductive behavior to understand life history traits demographics, physiology, habitat use, and resource requirements.

- Tracking individuals over time to understand important aspects of their life history such as growth and age to maturity.

- Evaluating life history, demographic, and population health information from stranding and fisheries bycatch datasets.

- Understanding impacts of change in environmental and ocean conditions on sea turtle abundance, distribution, and demographics.

- Estimating population abundance and analyzing trends.

- Monitoring fisheries impacts and working with the fishing industry to design fishing gear to minimize bycatch during commercial and recreational fishing operations.

- Building capacity and training to share the latest scientific techniques and tools to monitor sea turtle populations globally.

How You Can Help

Reduce Ocean Trash

Reduce marine debris and participate in coastal clean-up events. Responsibly dispose of fishing line - lost or discarded fish line kills hundreds of sea turtles and other animals every year. Trash in the environment can end up in the ocean and harm marine life.

Reduce plastic use to keep our beaches and oceans clean—carry reusable water bottles and shopping bags.

Refrain from releasing balloons—they can end up in the ocean where sea turtles can mistake them for prey like jellyfish or become entangled in lines.

Keep Your Distance

Admire sea turtles from a respectful distance by land or sea and follow these guidelines:

Don’t disturb nesting turtles, nests, or hatchlings. If interested, attend organized sea turtle watches that know how to safely observe sea turtles.

Never feed or attempt to feed or touch sea turtles as it changes their natural behavior and may make them more susceptible to harm.

Boat strikes are a serious threat to sea turtles. When boating, watch for sea turtles in the water, slow down, and steer around them. If you encounter them closer than 50 yards, put your engine in neutral to avoid injury. Remember, Go Slow, Sea Turtles Below!

Protect Sea Turtle Habitat

Beaches are paramount for healthy sea turtle populations since females come to the shore to deposit their eggs into nests.

Keep nesting beaches dark and safe at night. Turn off, shield, or redirect lights visible from the beach—lights disorient hatchlings and discourage nesting females from coming onto beaches to lay their eggs.

After a day at the beach, remove recreational beach equipment like chairs and umbrellas so sea turtles are not entrapped or turned away. Also, fill in holes and knock down sandcastles before you leave—they can become obstacles for nesting turtles or emerging hatchlings.

Do not drive on sea turtle nesting beaches—vehicles can deter females from nesting, directly strike hatchlings and nesting turtles, damage incubating nests, and create ruts that prevent hatchlings from reaching the sea.

Report Marine Life in Distress

If you see a stranded, injured, or entangled sea turtle, contact professional responders and scientists who can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Featured News

Leatherbacks are the largest sea turtles in the world, but all major populations are rapidly declining around the world because of persistent threats on their nesting beaches and in the marine environment. Photo credit: Jason Isley/Scubazoo. Photo for NOAA Fisheries use only.

Leatherbacks are the largest sea turtles in the world, but all major populations are rapidly declining around the world because of persistent threats on their nesting beaches and in the marine environment. Photo credit: Jason Isley/Scubazoo. Photo for NOAA Fisheries use only.

Field response efforts for endangered marine life, such as the Hawaiian monk seal, are among the activities NOAA Fisheries funded in 2024. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Field response efforts for endangered marine life, such as the Hawaiian monk seal, are among the activities NOAA Fisheries funded in 2024. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A green sea turtle swims in the waters off O’ahu, Hawaii. These turtles are herbivores, eating mostly seagrasses and algae. This diet gives their fat a greenish color (not their shells), which is where their name comes from. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Ali Bayless

A green sea turtle swims in the waters off O’ahu, Hawaii. These turtles are herbivores, eating mostly seagrasses and algae. This diet gives their fat a greenish color (not their shells), which is where their name comes from. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Ali Bayless

Management Overview

The olive ridley turtle Mexico's Pacific coast breeding populations are listed as endangered and all the other populations are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Additionally, the olive ridley turtle is listed under:

- Vulnerable according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List

- Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

In the United States, NOAA Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have joint jurisdiction for sea turtles, with NOAA having the lead in the marine environment and U.S. FWS having the lead on the nesting beaches. Both federal agencies, along with many state, and U.S. territory agencies and international partners, are working together to conserve and recover sea turtles and have issued regulations to eliminate or reduce threats to sea turtles.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Action

To help identify and guide the protection, conservation, and recovery of sea turtles, the ESA requires NOAA Fisheries and the U.S. FWS to develop and implement recovery plans which provide a blueprint for conservation of the species and measurable criteria to gauge progress toward recovery.

The major recovery actions for olive ridley turtles include:

- Protect sea turtles on nesting beaches and in marine environments.

- Protecting nesting and foraging habitats.

- Reducing bycatch in commercial and artisanal fisheries.

- Reducing the effects of entanglement and ingestion of marine debris.

- Reducing vessel strikes in coastal habitats.

- Working with partners internationally to protect turtles in all life-stages.

- Supporting research and conservation projects consistent with Recovery Plan priorities.

The recovery plan to recover and protect the U.S. Pacific populations of the olive ridley turtle was published in 1998.

The highly migratory behavior of sea turtles makes them shared resources among many nations, so conservation efforts for sea turtle populations must extend beyond national boundaries. This necessitates international collaboration and coordination. Learn more about international conservation efforts below.

Implementation

NOAA Fisheries is working to minimize effects from human activities that are detrimental to the recovery of olive ridley turtle populations in the United States and internationally. Together with our partners, we undertake numerous activities to support the goals of the olive ridley turtle recovery plan, with the ultimate goal of species recovery.

Efforts to conserve olive ridley turtles include:

- Protecting habitat.

- Reducing bycatch.

- Rescue, disentanglement, and rehabilitation.

- Eliminating the killing of turtles and the collection of their eggs.

- Eliminating the harassment of turtles on nesting beaches and foraging habitats through education and enforcement.

- Consulting with federal agencies to ensure their activities are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species.

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Bycatch

NOAA Fisheries is working to reduce the bycatch of sea turtles in commercial and artisanal fisheries. Our efforts are focused on documenting bycatch, understanding how, why, and where sea turtles are bycaught, and how to reduce that bycatch. We work with partners and the fishing industry to develop modifications to fishing gear and practices to reduce bycatch and/or to reduce bycatch injuries. These modifications are required in certain U.S. commercial fisheries including gillnets, longlines, pound nets, and trawls that unintentionally capture sea turtles. Measures include:

- Gear modifications.

- Changes to fishing practices.

- Time/area closures.

In the United States, NOAA Fisheries has worked closely with the shrimp trawl fishing industry to develop Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) to reduce the mortality of sea turtles bycaught in shrimp trawls. TEDs are required in the shrimp otter trawl fishery and, in early 2021, in larger vessels participating in skimmer trawl fishery.

Since 1989, the U.S. has prohibited the importation of shrimp harvested in a manner that adversely affects sea turtles. The import ban does not apply to nations that have adopted sea turtle protection programs comparable to that of the United States (i.e., require and enforce the use of TEDs) or to nations where bycatch in shrimp fisheries does not present a threat to sea turtles (for example, nations that fish for shrimp in areas where sea turtles do not occur). The U.S. Department of State is the principal implementing agency of this law while NOAA Fisheries serves as technical advisors and provides extensive TED training throughout the world.

We are also involved in cooperative gear research projects, implementation of changes to gear and fishing practices, and safe handling protocols designed to reduce sea turtle bycatch and mortality in the Gulf of America (formerly Gulf of Mexico) and Atlantic pelagic longline fisheries and the American Samoa and Hawaii-based longline fisheries.

Fisheries Observers

Bycatch in fishing gear is the primary human-caused source of sea turtle injury and mortality in U.S. waters. The most effective way to learn about bycatch is to place observers aboard fishing vessels. Observers collect important information that allows us to understand the amount and extent of bycatch, how turtles interact with the gear, and how bycatch reduction measures are working.

NOAA Fisheries determines which fisheries are required to carry observers, if requested to do so, through an annual determination. Observers may also be placed on fishing vessels through our authorities under the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

Responding to Strandings and Entanglements

A stranded sea turtle is one that is found on land or in the water and is either dead or is alive but unable to undergo normal activities and behaviors due to an injury, illness, or other problem. Most strandings are of individual turtles, and thousands are documented annually along the coasts of the United States and its territories. Organized networks of trained stranding responders are authorized to recover dead turtles or assist live turtles and document important information about the causes of strandings. These networks include federal, state, and private organizations. The actions taken by stranding network participants improve the survival of sick, injured, and entangled turtles while also helping scientists and managers expand their knowledge about threats to sea turtles and causes of mortality.

Because sea turtles spend most of their life at sea and out of sight, information learned from strandings are an important way for us to identify and monitor problems that threaten sea turtle populations.

Within the United States and its territories, there are three regional networks that serve to document and rescue stranded and entangled sea turtles:

- Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of America, and Caribbean: Coordinated under the Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN).

- Pacific Ocean (continental U.S. West Coast): Coordinated by NOAA’s West Coast Regional Office.

- Pacific Islands (Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands): Coordinated by NOAA’s Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center and the Pacific Islands Regional Office.

Male olive ridley sea turtle found on a Pacific Grove beach on October 5, 2011. Photo: Bob Yerena, NOAA.

The actions taken by stranding network participants improve the survivability of sick, injured, and entangled turtles while also helping scientists and managers to expand their knowledge about diseases and other threats that affect sea turtles in the marine environment and on land.

International Conservation Efforts

The conservation and recovery of sea turtles requires international cooperation and agreements to ensure the survival of these highly migratory animals. We work closely with partners in many countries across the globe to promote sea turtle conservation and recovery. Two international agreements specifically focused on sea turtle conservation are:

- Indian Ocean - South-East Asian (IOSEA) Marine Turtle Memorandum of Understanding

- Inter-American Convention (IAC) for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles

Additional international treaties and agreements that also protect sea turtles include:

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES): Listed in Appendix I, which prohibits international trade of wild flora and fauna.

- Cartagena Convention: Protected under Annex II of the Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) Protocol.

The Mexican government has played a vital role in the conservation of the olive ridley sea turtle. In 1990, Mexico declared a total ban on killing sea turtles, outlawing both the killing of turtles and the collection of eggs.

Regulatory History

The olive ridley turtle was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1978. The breeding populations in the Pacific coast of Mexico are listed as endangered—all other olive ridleys are listed as threatened.

In 1992, we finalized regulations to require turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawl fisheries to reduce sea turtle bycatch. Since then, we have updated these regulations as new information became available and TEDs were modified to improve their turtle exclusion rates.

We have implemented other measures to reduce sea turtle bycatch through regulations and permits under both the ESA and Magnuson-Stevens Act. These requirements include the use of large circle hooks in longline fisheries, time and area closures for gillnets, and modifications to pound net leaders.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 05/29/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the olive ridley sea turtle. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for the species.

Population Assessments

Sea turtle population assessments include information on the species’ abundance and distribution, life history, and human impacts. This information can help NOAA Fisheries evaluate the effectiveness of conservation and recovery measures, and can help guide actions to enhance recovery. To estimate population abundance, researchers conduct aerial and vessel-based surveys of selected areas and capture and mark turtles in the water and on beaches. We also incorporate data collected on nesting beaches, via stranding networks and from fisheries observer programs. Other information that informs sea turtle population assessments includes population structure (genetic analyses), age to maturity, survivorship of the various life stages (e.g., hatchling, juvenile, adult), foraging and reproductive behavior, movement and distribution, and habitat studies.

Tagging and Tracking Studies

Satellite telemetry allows researchers to track sea turtles as they migrate between and within foraging and nesting areas. Tags are designed and attached in a manner that minimizes disturbance and/or harm to the turtle. The data help us understand migration patterns, identify feeding areas, and identify where turtles overlap with their primary threats (e.g., fisheries, vessel traffic).

Olive ridley sea turtles nesting en masse during an "arribada" on Playa Ostional, Costa Rica on September 9, 2004. Photo: Michael Jensen.

Research to Reduce Bycatch in Fishing Gear

We observe fisheries to understand the level of sea turtle bycatch and the ways in which turtles interact with fishing gear. We work with partners and industry to develop modifications to fishing gear and/or fishing practices to reduce sea turtle bycatch while at the same time retaining a sustainable catch of targeted species. These efforts include the development of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) for use in trawl fisheries, use of circle hooks and certain bait types in longline fisheries, time and area closures/mesh size restrictions and low profile designs for gillnets, and modifications to pound net leaders.

Learn more about our fishing gear research

Sea Turtle Genetics

NOAA Fisheries’ National Sea Turtle Molecular Genetics Center serves as a worldwide central repository for sea turtle tissue and DNA samples and constitutes a major area of research supporting sea turtle conservation. For example, a turtle’s genetic “fingerprint” can be used to determine which nesting population it originated from.

Learn more about our turtle genetics and isotope studies

Life History Studies

Life history studies include gathering information on such things as migration patterns, where turtles nest and forage, growth rates, age to maturity, and sex ratios. This information is important in understanding key biological parameters that influence population trends and conservation status.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 05/29/2025

Documents

Biological Opinion on Continued Operation of the Hawaiʻi Deep-Set Longline Fishery, 2017

NOAA Fisheries issued a supplement in March 2017 to the biological opinion on the continued…

Turtle Excluder Device (TED) Compliance Policy

The April 18, 2014, biological opinion is the current Endangered Species Act (ESA) authorization…

Olive Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys Olivacea) 5-Year Review : Summary and Evaluation

The review is based on new information since the 2007 review and through January 2014. The review…

Southeastern Shrimp Otter (TED) Inspections Compliance Sea Turtle Capture Rates and TED Effectiveness

When legally-constructed Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) operate correctly in shrimp otter trawls, a…

Data & Maps

Recovery Action Database

Tracks the implementation of recovery actions from Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans.

Research

Sex Ratios of Olive Ridley Sea Turtles in the North Pacific High Seas: Implications for Climate Change Research

The first sex ratio estimates for olive ridleys foraging in the high seas of the North Pacific…

Southwest Fisheries Science Center Stock Assessments

Our stock assessments provide information on the dynamics of fish populations and scientific information to fishery managers regarding stock status, historical and future biomass, and recruitment trends.

Sea Turtle Research in the Pacific

Researching sea turtles across the U.S. Pacific Islands region.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 05/29/2025