Salmon Life Cycle and Seasonal Fishery Planning

The life cycles of salmon and steelhead along the West Coast are amazingly intricate. Understanding these complexities is important for predicting and reconstructing salmon and steelhead populations, and is vital for the management of seasonal fisheries.

Pacific salmon and steelhead have a diverse life cycle that begins in the rivers of Washington, Oregon, California, and Idaho where salmon spawn, or lay their eggs. Juveniles travel from freshwater to the Pacific Ocean and move great distances up and down the West Coast of North America. Salmon can spend up to several years at sea and cross international borders as they grow and mature. Some salmon are caught in ocean fisheries, some are caught in inland marine and freshwater fisheries, and some salmon complete their journey back to their freshwater spawning grounds to reproduce and begin the life cycle again. The migration pathways and return times vary between different salmon species and stocks. These differences are considered when estimating the returns of salmon and steelhead, and play an important role in planning for timing, type, location, and size of fisheries.

Knowledge of the different life cycles of Pacific salmon and steelhead can assist fishery managers in estimating the amount of harvest and developing management plans for each fishery. Co-managers of fisheries use information, such as the age when adult salmon return from the ocean to freshwater, to assess how many fish can be caught, how many fish could return, and to predict the vulnerability and resilience of these fish to environmental stressors.

Life Cycle of Salmon

The life histories of different salmon stocks along the West Coast is diverse and complex. While all salmon exhibit the same general life cycle components, different types or stocks of salmon can vary widely in how those components actually occur, or for how long.

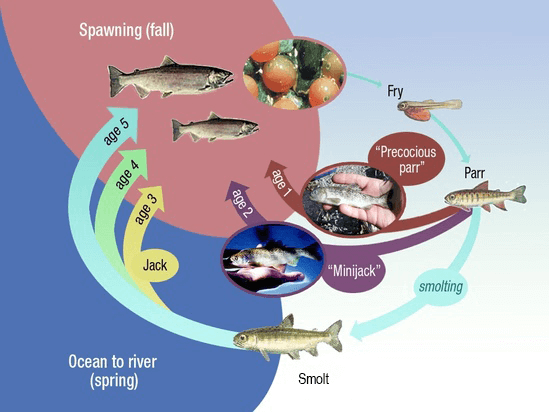

Adult salmon spawn in freshwater, where female salmon lay thousands of eggs that are fertilized by male salmon. Spawning can occur in spring, summer, fall, or winter and depends on the salmon species. After spawning, adult salmon die and their bodies provide nutrients for the freshwater ecosystem. Eggs are buried in gravel nests, called “redds,” and salmon can stay in their eggs for several weeks to months until they hatch. Once eggs hatch, the juvenile fish, called “fry,” can stay in the gravel nest to feed for 3-4 months. As juvenile salmon grow, they may remain in the freshwater rivers anywhere from a few hours to several years, depending on the species and other environmental factors. As juvenile salmon swim towards the ocean, they begin the process called smoltification–transitioning from living in freshwater to living in saltwater. The “smolts” may stay in estuaries from a few days to several weeks to feed, adapt, and prepare to enter the ocean.

Species of salmon can spend from 1 up to 6 years in the ocean as they mature and grow into adults. While in the ocean growing, salmon feed on small fish, squid, eels, and shrimp. When salmon are ready to reproduce, they migrate from the ocean back into freshwater rivers and streams to their spawning grounds. On their journey, they may encounter rapids, waterfalls, predators, and hydroelectric dams. Once salmon reach their freshwater spawning grounds, females dig a gravel nest, and the life cycle begins again.

Considerations in Fishery Plans

Learning about the life cycles of salmon and steelhead, the different ages of when they return, times of year and migration patterns, can help fishery managers target specific stocks and forecast the abundance of fish available in each fishery. Different salmon and steelhead life histories require different methods to estimate their abundance. The estimated abundance is used to regulate salmon fisheries and accurately plan the management of fisheries to ensure salmon stocks are managed sustainably.

The variety of movement and ages of salmon and steelhead can make them more vulnerable to environmental changes and stressors at different times of year, impacting their survival. Salmon and steelhead species with diverse life histories, with multiple ages returning to spawn, may be more resilient to climate and habitat changes because the generations of their species are spread over several years. In contrast, salmon species, such as coho and pink salmon, that return at consistent ages, may be more susceptible and impacted by catastrophic events, leading to the loss of whole generations of fish. With an understanding of salmon and steelhead reaction to stressors, management plans can be created that consider the size of fisheries, and aim to balance ecological and economic objectives.

Pacific Salmon and Steelhead Life Histories

Salmon and steelhead can return from the ocean to their freshwater habitats to spawn at any time of the year. Migration times and distance can fluctuate greatly within species. The fish “runs” may differ by species, seasons, and locations (though most of these fish return to the streams where they were born). This information is essential for fisheries managers to estimate population sizes, harvest amounts, and design fisheries management plans. When planning and managing fisheries, predictions about the different ages of returning fish, population sizes, and escapement objectives are considered. The variability in ages of returning salmon affects how many return each year and is an important consideration in estimating how many salmon will return to spawn each year, and to estimate the stock and harvest amount for the season. The analysis and evaluation of the potential number of salmon in the fishery is therefore complicated due to the various ages when salmon return.

Some fish may migrate far, some species may stay in the rivers for a long time before spawning, and other fish may be quick to return and spawn. The list below describes different salmon and steelhead species, and life cycle information used in fisheries management.

Pink salmon

Pink salmon are one of the fastest growing Pacific salmon species. After about 18 months in the ocean, pink salmon have reached maturity, and return to freshwater to spawn. Spawning occurs from August to October, when pink salmon are adult two-year-olds. Pink salmon mature and complete their life cycle in 2 years and this consistency has created distinct odd-year and even-year populations to use in planning their fisheries.

Chum salmon

Chum salmon are usually the last of the Pacific salmon that return to freshwater to spawn. After 3 to 4 years in the ocean, chum salmon reach full maturity and migrate back to their spawning grounds. Chum salmon spawn from generally late October to March, with peak spawning in early winter when the higher water flows in rivers. However, in some areas they can return as early as August. Chum salmon complete their life cycle between 3 to 6 years. The variety in ages of returning chum salmon is important when estimating population sizes and harvest amounts for fishery plans.

Sockeye salmon

Sockeye salmon mature and return to spawning grounds after 2 - 3 years in the ocean; some may stay longer and return after 4 – 5 years. Sockeye salmon spawn from July to late October when they are mature. Their lifespan is usually about 5 years; however, in the Pacific Northwest, sockeye salmon lifespan is more commonly 4 years. By understanding the general age of returning sockeye salmon, fishery managers can predict stock sizes and develop fishery proposals.

Learn more about Sockeye salmon

Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon can spend from 1 to 6 years growing in the ocean. Chinook salmon mature between the ages of 2 to 7; however, they are usually 3-4 years old when they return to spawn. The timing of when Chinook salmon migrate from the ocean to their spawning grounds divides Chinook salmon into four distinct population “runs”. These distinct populations are named for the season when most of the fish run return from the ocean to spawn: spring, summer, fall, or winter. Some Chinook salmon enter freshwater from the ocean and are ready to spawn soon after entering freshwater. Others come from the ocean and need to spend time maturing in freshwater before they are ready to spawn.

The distance and time it takes for Chinook salmon to migrate to their spawning grounds can range from relatively short to very long depending on the population. Knowledge of the varying distinct Chinook salmon populations, ages, and migration patterns can assist fishery managers in the estimation and reconstruction of populations, and plan fisheries.

Spring-run Chinook salmon return to their spawning grounds at different ages, from 3 to 5 years of age. The migration from the ocean to their spawning grounds begins in April through July, with peak migration occurring in May. Spawning begins in August and continues through early November.

Summer-run Chinook salmon may return to their spawning grounds from 2 to 5 years of age. Traveling back to their spawning grounds occurs from June to August. Spawning begins in late August until November.

Fall-run Chinook salmon are the most common group of Chinook salmon on the West Coast. Most fall-run Chinook salmon can spend 3-4 years in the ocean before migrating to their spawning grounds, however some can return at 2 or 5 years old. The journey to spawning grounds begins in late July, peaking in September, and ends in December. Spawning happens from October through December. The most common age of returning and spawning adults is 4 years old.

Winter-run Chinook salmon may return to their spawning grounds after 1 to 3 years in the ocean. The migration to their spawning grounds occurs from December through May, with peak migration in March. Spawning occurs from mid-April to early August.

Learn more about Chinook salmon

Coho salmon

Coho salmon remain in the ocean for about 18 months to 2 years, and begin their migration back to spawning grounds from September through December. Coho salmon spawn in November and December, and the lifespan of coho salmon is usually 3 to 4 years. However, some male coho reach maturity early and migrate back to freshwater streams as 2-year-old “jacks.” The “jack” returns may provide an estimate of adult abundance for the following year and assist in fishery plans.

Steelhead

Steelhead can spend from 1 to 4 years in the ocean before traveling to their spawning grounds. There are two general types of steelhead runs, named for the season when most of the fish run return from the ocean: winter and summer.

Winter-run Steelhead return from the ocean at age 4 or 5 years, and travel to their spawning grounds from November to April. Winter-run steelhead are very mature fish and begin spawning soon after they arrive.

Summer-run Steelhead usually return from the ocean at age 3 and migrate to their spawning grounds from April to September. The summer-run steelhead are typically immature fish and need several months of maturing in the freshwater before spawning.

Both steelhead stocks spawn from winter to early spring (January to April). The lifespan of steelhead varies from 5 up to 11 years.

Steelhead are different from Pacific salmon because steelhead do not all die once they spawn. Steelhead can survive after spawning and can migrate to the ocean and back to their spawning grounds again in the future, laying eggs more than once in their lifespan. The seasonal differences in steelhead migrations and multiple trips to spawning grounds are considered when predictions are made about the number of returning steelhead for the season and their fisheries management.

Learn more about Pacific salmon on the West Coast:

- The incredible journey of salmon educational resources

- Pacific Salmon Life History Research

- Salmon Survival Game

Salmon returns and seasonal fishery strategies

Pacific salmon fisheries have cultural, economic, and social importance to many communities. Salmon fisheries can fluctuate yearly depending on the number of salmon that return that year, the consideration of ecosystem shifts, and coastal communities’ priorities. To navigate yearly changes and involve interested parties, fisheries on the West Coast are co-managed by tribal governments and the states of Washington, Oregon, California, and Idaho. Co-management is a continuous and cooperative process that works towards the goals of conservation of salmon fisheries and the fostering of strong coastal communities.

Fisheries are managed to ensure enough salmon return to their home streams to spawn and contribute to the next generation. Salmon are caught in ocean fisheries (i.e. commercial, recreational, tribal) at different times and places because salmon migrate back to freshwater at different seasonal periods. Some salmon and steelhead may return in the spring and summer, while others may return in the fall or winter. This diversity in life cycles is considered in the estimation processes used to plan seasonal fishery management, and fisheries are shaped to harvest the stronger salmon returns and minimize harvest on weaker stocks.

Salmon life histories contribute to the strength, endurance, and resiliency of salmon. The variety of salmon and steelhead life cycles allows salmon and steelhead to handle changes in the environment.

Predicting when salmon groups will return to freshwater helps to guide managers on when specific salmon fisheries should be opened and closed. By understanding when salmon will return to their freshwater spawning grounds, fishery managers can estimate the number of salmon that may be caught in fisheries, may be eaten by predators, and may return to their spawning grounds. Predictions about salmon returns can also help when managing interactions between multiple fisheries in the same location. Understanding the differences in life cycles between salmon populations helps with the design of fishery management plans that encourage sustainability and also meet fisheries’ needs.

Abundance-based Fisheries Management

Salmon fishery management is based on the abundance of salmon each year. In years with low abundance, there is a reduction in fishing, while an increase in fishing occurs during years of high abundance. This strategy is called abundance-based fisheries management.

Salmon fisheries are located in the ocean and inland waters throughout the fishery season. During the season, catch records are kept and shared among fishery co-managers. The catch records are used to determine the total amount of fish caught, and to ensure that the fishery is staying within the catch limits. Collection of harvest information allows changes to be made during the fishing season to update the number of fish harvested and to make adjustments to season length, fisheries regulations, and allowable catch. There is also extensive postseason management and reporting used to forecast for the next season. The active approach of monitoring fisheries helps the co-managers reduce the chances of overharvesting.

More Information

More Information

- West Coast Salmon and Steelhead Fisheries Management

- Salmon and Steelhead Fisheries in the Mainstem Columbia River and Snake River

- Puget Sound Salmon and Steelhead Fisheries

- Pacific Fishery Management Council

- Pacific Salmon Treaty and the Pacific Salmon Commission

- Ecosystem Interactions and Pacific Salmon

- West Coast Salmon and Steelhead Fisheries Management Map

- Pacific Salmon and Steelhead Fisheries Management Glossary