A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

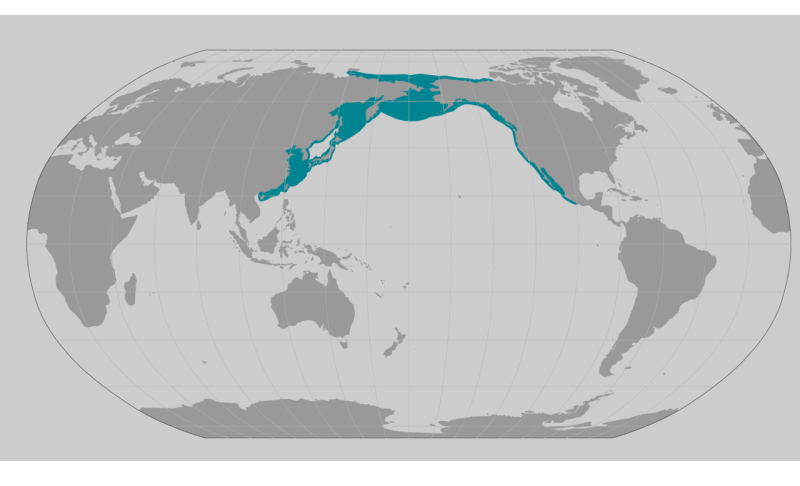

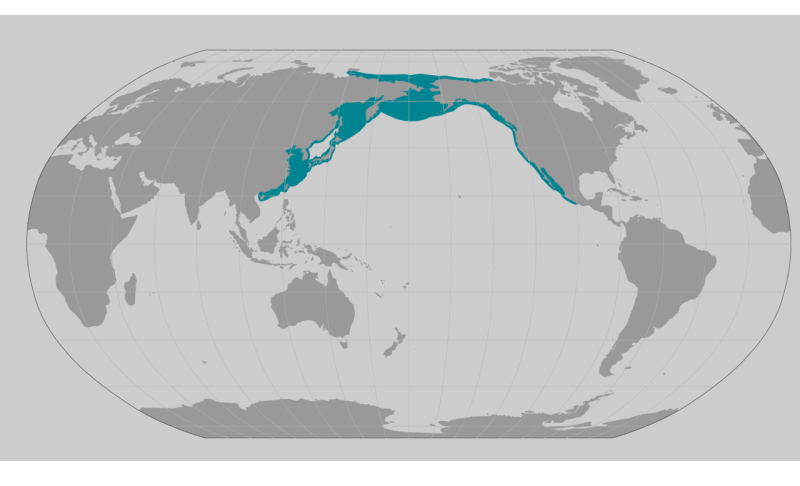

Once common throughout the Northern Hemisphere, gray whales are now only regularly found in the North Pacific Ocean where there are two extant populations, one in the eastern and one in the western North Pacific.

Gray whales earned the nickname “devil fish” because of their aggressive reactions when harpooned. Commercial whaling rapidly brought both Pacific populations to near extinction. International conservation measures were enacted in the 1930s and 1940s to protect whales from over-exploitation, and in the mid-1980s the International Whaling Commission instituted a moratorium on commercial whaling.

Gray whales are known for their curiosity toward boats in some locations and are the focus of whale watching and ecotourism along the west coast of North America. Gray whales make one of the longest annual migrations of any mammal, traveling about 10,000 miles round-trip and in some cases upwards of 14,000 miles. On their migration routes they face threats from vessel strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and other sources of disturbance.

NOAA Fisheries works to conserve gray whales through collaborative management, integrated science, partnerships, and outreach. Our scientists use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and rescue gray whales in distress (e.g., disentanglement and stranding response). We strive to reduce the harmful effects of human activities, such as fisheries interactions, noise, and pollution, through management actions based on science, public input, and public outreach.

Population Status

NOAA Fisheries estimates the population size (also called a stock) for gray whales in its stock assessment reports. Shore-based observers have conducted systematic counts of eastern North Pacific gray whales migrating south along the central California coast in most years since 1967. All gray whale stocks are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The eastern stock or Distinct Population Segment (DPS) was once listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act but successfully recovered and was delisted in 1994. The western stock or DPS remains very low in number and is listed as endangered under the ESA and depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The western stock is estimated to include fewer than 300 individuals based on photo-identification data collected off Sakhalin Island and southeastern Kamchatka, Russia.

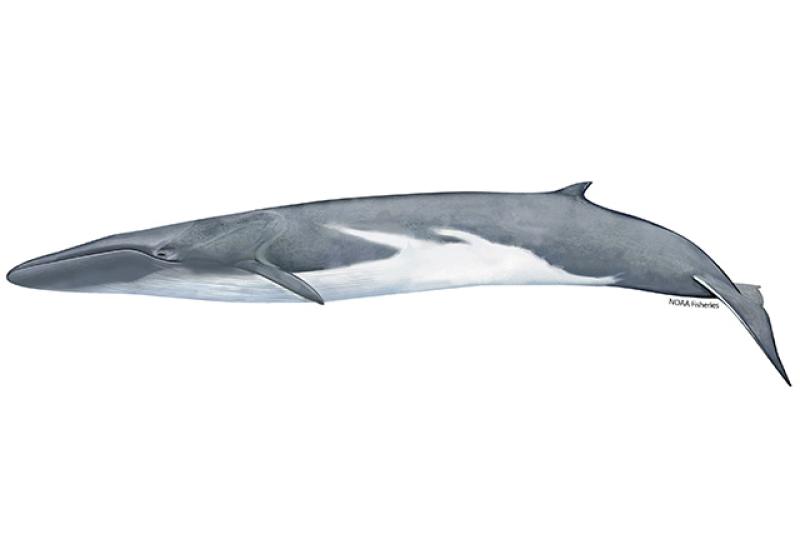

Appearance

These large whales can grow to about 49 feet long and weigh approximately 90,000 pounds. Females are slightly larger than males. Gray whales have a mottled gray body with small eyes located just above the corners of the mouth. Their pectoral flippers are broad, paddle-shaped, and pointed at the tips. Lacking a dorsal fin, they instead have a dorsal hump about two-thirds of the way back on the body, and a series of 6 to 12 small bumps, called “knuckles,” between the dorsal hump and the tail flukes. The tail flukes are nearly 10 feet wide with S-shaped trailing edges and a deep median notch.

Calves are typically born dark gray and lighten as they age to brownish-gray or light gray. All gray whales are mottled with lighter patches. They have barnacles and whale lice (i.e., cyamids) on their bodies, with higher concentrations found on the head and tail.

Behavior and Diet

Gray whales are frequently observed traveling alone or in small, mostly unstable groups. Although large aggregations may be seen in feeding and breeding grounds. Like other baleen whales, long-term bonds between individuals are thought to be rare.

They are primarily bottom feeders that consume a wide range of benthic (sea floor) and epibenthic (above the sea floor) invertebrates, such as amphipods. Gray whales suck sediment and food from the sea floor by rolling on their sides and swimming slowly along, filtering their food through 130 to 180 coarse baleen plates on each side of their upper jaw. In doing so, they often leave long trails of mud behind them and "feeding pits" on the seafloor. Killer whales prey upon gray whales.

Where They Live

Gray whales are found mainly in shallow coastal waters in the North Pacific Ocean, although during migration, they do sometimes cross deep waters far from shore. There are two geographic distributions of gray whales in the North Pacific:

- The eastern North Pacific stock or DPS, found along the west coast of North America

- The western North Pacific stock or DPS, primarily found along the coast of eastern Asia

Most of the eastern North Pacific stock gray whales spend the summer feeding in the northern Bering and Chukchi seas, but some feed along the Pacific coast during the summer, in waters off of Southeast Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. In the fall, eastern North Pacific gray whales migrate from their summer feeding grounds, heading south along the coast of North America to spend the winter in their wintering and calving areas off the coast of Baja California, Mexico. Calves are born during migration or in the shallow lagoons and bays of Mexico from early January to mid-February. From mid-February to May, eastern North Pacific gray whales can be seen migrating northward along the U.S. West Coast. Although western and eastern stocks of gray whales were thought to be relatively isolated from each other, recent satellite tagging data and photo-identification and genetic matches have shown that at least some western North Pacific gray whales migrate across the northern Gulf of Alaska, and along the west coast of British Columbia, the United States, and Mexico.

World map providing approximate representation of the gray whale's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the gray whale's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Gray whales become sexually mature between 6 and 12 years, with the average of maturity being about 8 to 9 years old. After 12 to 13 months of gestation, females give birth to a single calf. Newborn calves are approximately 14 to 16 feet long and weigh about 2,000 pounds. The average and maximum lifespan of gray whales is unknown, although one female was estimated at 75 to 80 years old after death.

Threats

Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Gray whales are at high risk of becoming entangled in fishing gear. Once entangled, whales may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances or be anchored in place and unable to swim. Events such as these result in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury, which may ultimately lead to death.

Vessel Strikes

Collisions with all sizes and types of vessels are one of the primary threats to marine mammals, particularly large whales. Gray whales are vulnerable to vessel strikes because they feed and migrate along the U.S. West Coast, which has some of the world’s heaviest vessel traffic associated with some of the largest ports in the country. Gray whales may also be vulnerable to vessel strikes in the inland waters of Washington and in feeding areas along the Pacific coast.

Disturbance from Whale Watching Activities

Whale watching has become an important recreational industry in several communities along the North American coast from British Columbia, Canada, to the gray whale wintering lagoons of Baja California, Mexico. Whale watching along this route may lead to disturbance and affect gray whale behavior.

Ocean Noise

Underwater noise can reduce the ability of whales to communicate with each other, increase their stress levels, interrupt their normal behavior and displace them from areas important to their survival.

Habitat Degradation

Habitat modification and degradation, such as that resulting from offshore oil and gas development may affect gray whale foraging habitat off Sakhalin Island, Russia. Platforms, pipelines, and other types of infrastructure construction activities have the potential of impacting gray whale prey communities.

Climate Change

The impacts of climate change on baleen whales are unknown, but it is considered one of the largest threats facing high latitude regions where many gray whales forage. Most notably, the timing and distribution of sea ice coverage is changing dramatically with altered oceanographic conditions. Any resulting changes in prey distribution could lead to changes in foraging behavior, nutritional stress, and diminished reproduction for gray whales. Additionally, changing water temperature and currents could impact the timing of environmental cues important for navigation and migration.

Scientific Classification

| Animalia |

Chordata |

Mammalia |

Cetartiodactyla |

Eschrichtiidae |

Eschrichtius |

robustus |

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024