Gray Whale

Eschrichtius robustus

Protected Status

Quick Facts

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Once common throughout the Northern Hemisphere, gray whales are now only regularly found in the North Pacific Ocean where there are two extant populations, one in the eastern and one in the western North Pacific.

Gray whales earned the nickname “devil fish” because of their aggressive reactions when harpooned. Commercial whaling rapidly brought both Pacific populations to near extinction. International conservation measures were enacted in the 1930s and 1940s to protect whales from over-exploitation, and in the mid-1980s the International Whaling Commission instituted a moratorium on commercial whaling.

Gray whales are known for their curiosity toward boats in some locations and are the focus of whale watching and ecotourism along the west coast of North America. Gray whales make one of the longest annual migrations of any mammal, traveling about 10,000 miles round-trip and in some cases upwards of 14,000 miles. On their migration routes they face threats from vessel strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and other sources of disturbance.

NOAA Fisheries works to conserve gray whales through collaborative management, integrated science, partnerships, and outreach. Our scientists use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and rescue gray whales in distress (e.g., disentanglement and stranding response). We strive to reduce the harmful effects of human activities, such as fisheries interactions, noise, and pollution, through management actions based on science, public input, and public outreach.

Population Status

NOAA Fisheries estimates the population size (also called a stock) for gray whales in its stock assessment reports. Shore-based observers have conducted systematic counts of eastern North Pacific gray whales migrating south along the central California coast in most years since 1967. All gray whale stocks are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The eastern stock or Distinct Population Segment (DPS) was once listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act but successfully recovered and was delisted in 1994. The western stock or DPS remains very low in number and is listed as endangered under the ESA and depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The western stock is estimated to include fewer than 300 individuals based on photo-identification data collected off Sakhalin Island and southeastern Kamchatka, Russia.

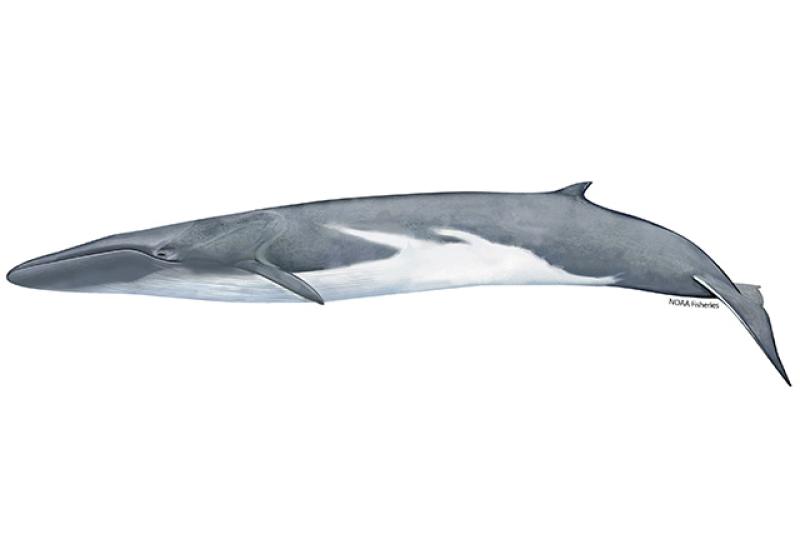

Appearance

These large whales can grow to about 49 feet long and weigh approximately 90,000 pounds. Females are slightly larger than males. Gray whales have a mottled gray body with small eyes located just above the corners of the mouth. Their pectoral flippers are broad, paddle-shaped, and pointed at the tips. Lacking a dorsal fin, they instead have a dorsal hump about two-thirds of the way back on the body, and a series of 6 to 12 small bumps, called “knuckles,” between the dorsal hump and the tail flukes. The tail flukes are nearly 10 feet wide with S-shaped trailing edges and a deep median notch.

Calves are typically born dark gray and lighten as they age to brownish-gray or light gray. All gray whales are mottled with lighter patches. They have barnacles and whale lice (i.e., cyamids) on their bodies, with higher concentrations found on the head and tail.

Behavior and Diet

Gray whales are frequently observed traveling alone or in small, mostly unstable groups. Although large aggregations may be seen in feeding and breeding grounds. Like other baleen whales, long-term bonds between individuals are thought to be rare.

They are primarily bottom feeders that consume a wide range of benthic (sea floor) and epibenthic (above the sea floor) invertebrates, such as amphipods. Gray whales suck sediment and food from the sea floor by rolling on their sides and swimming slowly along, filtering their food through 130 to 180 coarse baleen plates on each side of their upper jaw. In doing so, they often leave long trails of mud behind them and "feeding pits" on the seafloor. Killer whales prey upon gray whales.

Where They Live

Gray whales are found mainly in shallow coastal waters in the North Pacific Ocean, although during migration, they do sometimes cross deep waters far from shore. There are two geographic distributions of gray whales in the North Pacific:

- The eastern North Pacific stock or DPS, found along the west coast of North America

- The western North Pacific stock or DPS, primarily found along the coast of eastern Asia

Most of the eastern North Pacific stock gray whales spend the summer feeding in the northern Bering and Chukchi seas, but some feed along the Pacific coast during the summer, in waters off of Southeast Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. In the fall, eastern North Pacific gray whales migrate from their summer feeding grounds, heading south along the coast of North America to spend the winter in their wintering and calving areas off the coast of Baja California, Mexico. Calves are born during migration or in the shallow lagoons and bays of Mexico from early January to mid-February. From mid-February to May, eastern North Pacific gray whales can be seen migrating northward along the U.S. West Coast. Although western and eastern stocks of gray whales were thought to be relatively isolated from each other, recent satellite tagging data and photo-identification and genetic matches have shown that at least some western North Pacific gray whales migrate across the northern Gulf of Alaska, and along the west coast of British Columbia, the United States, and Mexico.

World map providing approximate representation of the gray whale's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the gray whale's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Gray whales become sexually mature between 6 and 12 years, with the average of maturity being about 8 to 9 years old. After 12 to 13 months of gestation, females give birth to a single calf. Newborn calves are approximately 14 to 16 feet long and weigh about 2,000 pounds. The average and maximum lifespan of gray whales is unknown, although one female was estimated at 75 to 80 years old after death.

Threats

Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Gray whales are at high risk of becoming entangled in fishing gear. Once entangled, whales may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances or be anchored in place and unable to swim. Events such as these result in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury, which may ultimately lead to death.

Vessel Strikes

Collisions with all sizes and types of vessels are one of the primary threats to marine mammals, particularly large whales. Gray whales are vulnerable to vessel strikes because they feed and migrate along the U.S. West Coast, which has some of the world’s heaviest vessel traffic associated with some of the largest ports in the country. Gray whales may also be vulnerable to vessel strikes in the inland waters of Washington and in feeding areas along the Pacific coast.

Disturbance from Whale Watching Activities

Whale watching has become an important recreational industry in several communities along the North American coast from British Columbia, Canada, to the gray whale wintering lagoons of Baja California, Mexico. Whale watching along this route may lead to disturbance and affect gray whale behavior.

Ocean Noise

Underwater noise can reduce the ability of whales to communicate with each other, increase their stress levels, interrupt their normal behavior and displace them from areas important to their survival.

Habitat Degradation

Habitat modification and degradation, such as that resulting from offshore oil and gas development may affect gray whale foraging habitat off Sakhalin Island, Russia. Platforms, pipelines, and other types of infrastructure construction activities have the potential of impacting gray whale prey communities.

Climate Change

The impacts of climate change on baleen whales are unknown, but it is considered one of the largest threats facing high latitude regions where many gray whales forage. Most notably, the timing and distribution of sea ice coverage is changing dramatically with altered oceanographic conditions. Any resulting changes in prey distribution could lead to changes in foraging behavior, nutritional stress, and diminished reproduction for gray whales. Additionally, changing water temperature and currents could impact the timing of environmental cues important for navigation and migration.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Chordata | Class | Mammalia | Order | Cetartiodactyla | Family | Eschrichtiidae | Genus | Eschrichtius | Species | robustus |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024

What We Do

Conservation & Management

All gray whales are protected under the MMPA. Our work strives to protect gray whales by:

- Reducing interactions with commercial and recreational fishing gear

- Responding to dead, injured, or entangled gray whales

- Encouraging responsible viewing of gray whales

- Minimizing the effects of vessel disturbance, noise, and other types of human impacts

Science

Our research projects have helped us better understand gray whales and the challenges they face. Our work includes:

- Stock assessments

- Noise-response measurement

- Satellite tagging and tracking

- Photo-identification

- Photogrammetric assessment of body condition and health

- Genetic population structure

- Passive acoustic monitoring of whale presence and ambient noise levels

How You Can Help

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all large whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Reduce Speed and Be on the Lookout

Vessel collisions are a major cause of injury and death for whales. Here are some tips to avoid collisions:

Be Whale Aware. Know where whales occur (habitat).

Watch your speed in areas of known marine mammal occurrence. Keep speeds to 10 knots or less to reduce potential for injury.

Keep a sharp lookout. Look for blows, dorsal fins, tail flukes, etc. However, be aware that most captains report never seeing a whale prior to colliding with it.

Protect your boat, protect your passengers. Boats can be heavily damaged and even "totalled" after colliding with a large whale. Collisions can also injure passengers.

Keep your distance. Stay at least 100 yards away.

Stop immediately if within 100 yards. Slowly distance your vessel from the whale.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

Gray whale mother and calf on northbound migration. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Gray whale mother and calf on northbound migration. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Eastern North Pacific Gray Whales Continue Decline After Downturn During Unusual Mortality Event

Responders approach the entangled whale off the Palos Verdes Peninsula, using a long pole with specialized blade to reach and sever the net and lines entangling the whale. Photo by Marine Mammal Care Center Los Angeles, under NOAA Fisheries Permit #24359.

Responders approach the entangled whale off the Palos Verdes Peninsula, using a long pole with specialized blade to reach and sever the net and lines entangling the whale. Photo by Marine Mammal Care Center Los Angeles, under NOAA Fisheries Permit #24359.

Trained Team Releases Gray Whale Entangled in Gillnet off California’s Palos Verdes Peninsula

The Makah Tribe long hunted whales in hand-carved canoes, such as this one landing at Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula about 1900. They voluntarily stopped hunting gray whales in 1928 as commercial whaling depleted the species, which has since recovered in the eastern Pacific. Photo courtesy Museum of History and Industry, Negative Number 88.33.122.

The Makah Tribe long hunted whales in hand-carved canoes, such as this one landing at Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula about 1900. They voluntarily stopped hunting gray whales in 1928 as commercial whaling depleted the species, which has since recovered in the eastern Pacific. Photo courtesy Museum of History and Industry, Negative Number 88.33.122.

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Scientists are using an unmanned aerial vehicle to produce very precise overhead images of gray whales, then analyzing the images to understand how environmental conditions affect the health of adult females and ultimately the reproductive success of the population. Credit: NOAA

A gray whale and her calf migrate north along the California coast on their way to summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. Scientists are using an unmanned aerial vehicle to produce very precise overhead images of gray whales, then analyzing the images to understand how environmental conditions affect the health of adult females and ultimately the reproductive success of the population. Credit: NOAA

Management Overview

The gray whale western North Pacific distinct population segment (DPS) is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

The gray whale is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

The western North Pacific DPS is depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Additionally, the gray whale is listed under:

- Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Conservation Efforts

Reducing Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Gray whales are incidentally caught as bycatch and entangled in fishing gear, leading to deaths and serious injuries. We work with fishermen, industry, non-government organizations, and academia to find approaches and strategies for reducing bycatch in U.S. fisheries.

Learn more about bycatch and fisheries interactions

Reducing Vessel Strikes

Collisions between whales and large vessels often go unnoticed and unreported, even though whales can be injured or killed, and vessels can sustain damage. We have taken steps to reduce the threat of vessel collisions to gray whales. For example, NOAA Fisheries has collaborated with NOAA Sanctuaries and the U.S. Coast Guard to effect changes in shipping lanes that should help reduce the risk of vessels striking large whales.

NOAA Fisheries has also worked with the Southern California Marine Exchange to coordinate meetings with shipping industry leaders to discuss the issue of large whale vessel strikes. NOAA works with the U.S. Coast Guard, industry representatives, and the NOAA Weather Service to prevent strikes by alerting mariners of the presence of large whales to raise awareness and help prevent strikes.

We recommend that operators of large vessels do the following to help reduce the risk of ship strikes:

- Learn when the seasonal abundance of large whales is in shipping lanes

- Listen for and heed advisories

- Consult the Local Notice to Mariners or Coast Pilot for more information

- Keep a sharp look-out for whales; post extra crew on the bow to watch, if possible

- Reduce speeds while in the advisory zones or in areas of high seasonal or local whale abundance

- Re-route the vessel to avoid areas of high whale abundance

Minimizing Whale Watching Harassment

Admiring whales from a distance is the safest and most responsible way to view them in their natural habitat. NOAA Fisheries supports responsible viewing of marine mammals in the wild and has adopted a guideline to observe all large whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards by sea or land. NOAA Fisheries’ West Coast Region encourages the public to be “whale wise” and has also published its own safe viewing guidelines and outreach materials for boaters, paddlers, and drone operators on the West Coast. NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Region has also created Marine Mammal Viewing Guidelines for reducing disturbance while watching whales, sea lions, seals, dolphins, and porpoise from boats, planes, and helicopters.

Learn more about marine life viewing guidelines

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Gray whales have been part of declared unusual mortality events in the past. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Get information on active and past UMEs

Get an overview of marine mammal UMEs

Addressing Ocean Noise

Noise pollution can threaten whale populations, interrupting their normal behavior and displacing them from areas important to their survival. NOAA Fisheries is investigating all aspects of acoustic communication and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on whale behavior and hearing. In 2018, we issued revised technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic sound on marine mammal hearing.

Regulatory History

Beginning in the mid-1930s, gray whales were protected under a commercial hunting ban adopted by the League of Nations. This ban was the first international agreement to protect a whale species from commercial whaling operations. The ban on commercial gray whale catches has continued since the late 1940s under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, administered by the International Whaling Commission (IWC). Gray whales are still hunted by native people of Chukotka, Russia and are subject to catch limits under the IWC's aboriginal subsistence whaling scheme.

Today, gray whales are protected under the MMPA. The eastern North Pacific stock was once listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act but was delisted in 1994 based on evidence that the population had nearly recovered to its estimated original population size and was not in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. In 1999, NOAA Fisheries conducted a review of the status of the eastern North Pacific stock of gray whales (PDF, 106 pages) and recommended the continuation of its classification as non-threatened based on the continued growth of the population. We continue to monitor the abundance and calf production of the stock, especially in light of recent climatic changes occurring in their arctic feeding grounds. The western North Pacific stock or DPS of gray whales has not recovered. It is listed as endangered under the ESA and depleted under the MMPA.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research on the biology, behavior, and ecology of gray whales. The results are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this species.

Stock Assessments

Determining the size of gray whale populations helps resource managers gauge the success of NOAA Fisheries’ conservation measures. Our scientists collect and present these data in annual stock assessment reports. NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fisheries Science Center conducts regular surveys of eastern North Pacific gray whale abundance and calf production. The data time series for abundance estimation extends from 1967 to 2020 and most recently has integrated use of fixed-wing Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) platforms and infrared cameras to aid visual observers. The calf production time series has been collected every year 1994 to 2020 and combines visual observations with UAS photogrammetry overflights.

Satellite Tagging

Eastern North Pacific gray whales migrate annually between wintering grounds in the lagoons of Baja California, Mexico, and summer feeding grounds in the Arctic. This migration follows the coast of North America and overlaps with areas of heavy coastal shipping, commercial fishing, and resource exploration. Evaluating risk from these activities requires fine-scale data on precise migration routes. In March 2012, scientists from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fisheries Science Center and Mexican collaborators deployed small satellite dart tags on adult gray whales to monitor their fine-scale migration route through the coastal waters off Baja California, Mexico, and southern California.

UAV Photo-Identification and Body Condition Assessment

The Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) program at NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center has been at the forefront of the development and application of UAS technologies within the marine wildlife research community for over a decade. Photographic assessment of eastern North Pacific gray whale body condition and individual identification using photogrammetry sampling with an unmanned octocopter has been conducted 2015 to 2020. Vertical images are used to measure the condition of mothers and the growth of their calves. UAS photographs are also being evaluated for matching individual whales from aerial and shore-based photo-identifications based on their natural markings. Once validated, this approach will enable aerial identifications to be linked to longer-term oblique-view photo-identification catalogs to more precisely quantify calving intervals and relate photogrammetry measurements to population identity and life history parameters.

Photo-Identification Studies

NOAA Fisheries' West Coast Regional Office and Marine Mammal Laboratory fund photo-identification studies to better understand gray whale stock structure, distribution and abundance. This information allows us to follow the animals over time and learn about their use of habitat and their feeding patterns. It can also provide information on the relationship between the eastern and western populations.

Gray Whales in Alaska

Our research on the population dynamics, diet and foraging behavior, distribution, and movement patterns of gray whales provides information crucial for understanding and protecting gray whale populations in Alaska.

More Information

Recent Science Blogs

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024

Documents

Biological Opinion NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources, Permits and Conservation Division, Eareckson Air Station Long-term Fuel Pier Repairs, Shemya Island, Alaska

This opinion considers the effects of all in-water activities including vessel transit of materials…

Makah Tribe Permit Application to Hunt Gray Whales

Application for a Hunt Permit under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and Regulations Governing the…

DPS Analysis of Western North Pacific Gray Whales under the ESA

NOAA Technical Memo

Western North Pacific DPS of Gray Whale 5-Year Review

This document is the ESA 5-year review of the species based on the best available data.

Data & Maps

2019 Aerial Surveys Of Arctic Marine Mammals

Distribution and Relative Abundance of Marine Mammals in the Eastern Chukchi Sea, Eastern and…

Research

Marine Mammal Life History

Data collected from stranded and bycaught marine mammals are critical to understanding their life history

International Collaboration To Monitor And Respond To Tagged Gray Whale

NOAA Fisheries and Canadian partners working together, sharing information and expertise to respond to gray whale.

Outreach & Education

Actividad sobre residuos marinos en una ballena gris (en español)

En esta actividad, los participantes examinarán el contenido del estómago de una ballena gris que…

Gray Whale Marine Debris Activity

In this activity, participants will examine the stomach contents of a gray whale that stranded on…

U.S. Whale Entanglement Response Level 1 - Alaska Region First Responder Training

Level 1 First Responder training to prepare recreational and commercial boaters to report whale…

Acoustic Studies Sound Board Of Marine Mammals In Alaska

This resource features passive acoustic sound clips of many amazing marine mammals that can be…

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/26/2024