White Abalone

White Abalone

Haliotis sorenseni

Protected Status

Quick Facts

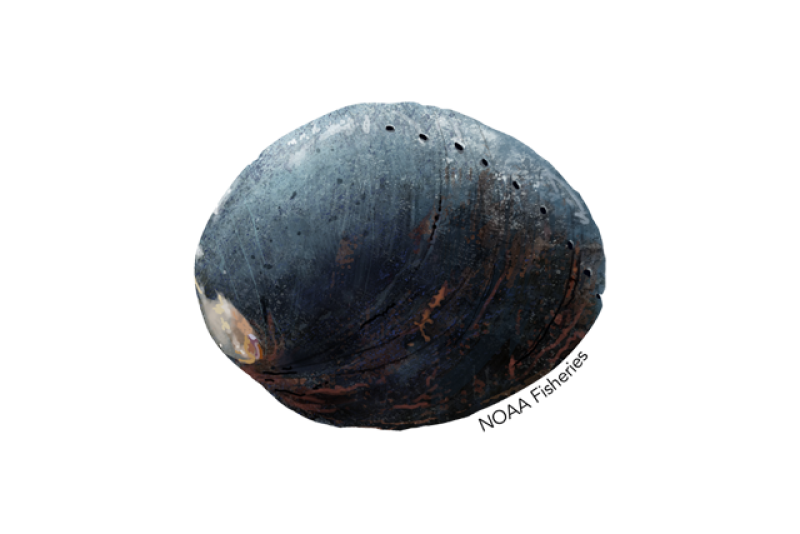

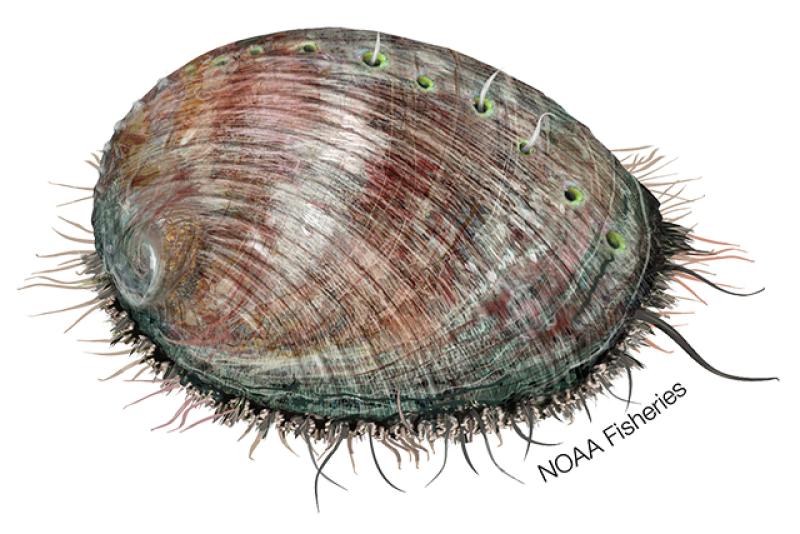

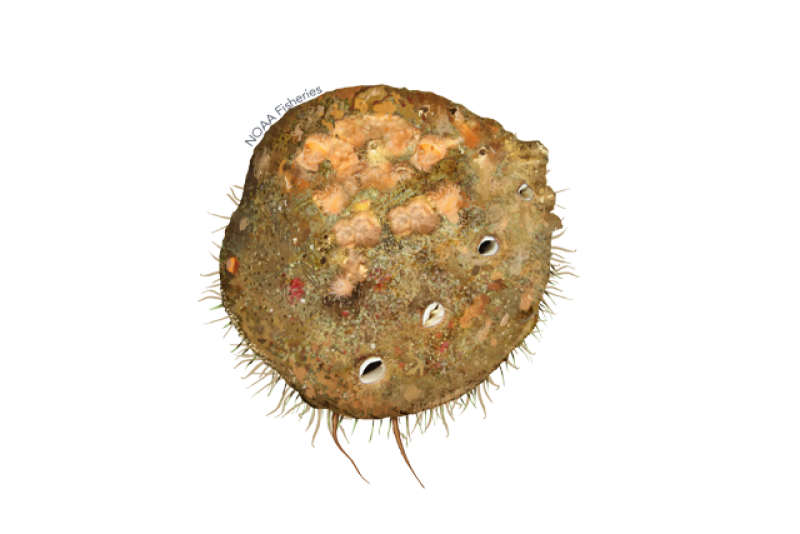

White abalone. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

White abalone. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

White abalone. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

White abalone. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

White abalone. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

White abalone. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

White abalone belong to a group of algae-eating marine snails that were once common in California. They once numbered in the millions off the California coast, but now they are endangered.

Before the time of commercial fisheries, native people along California’s coast ate abalone for thousands of years. Large groups of abalone shells indicating human settlement, or “middens,” date back 7,400 years. Abalone shells were also traded along routes starting in southern California and reaching east of the Mississippi River.

White abalone continue to live in the coastal waters of southern California and Mexico. They are “broadcast spawners,” releasing eggs and sperm into the water by the millions when environmental conditions are right. Their strong, muscular “foot” allows them to hold tightly to rocks and other hard surfaces while their oval-shaped shells protect them from predators. Although fishing for white abalone has been illegal in California since 1997, the high price of abalone meat makes them a target of poachers.

White abalone were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 2001, and were the first marine invertebrate to be listed. White abalone are one of NOAA Fisheries' Species in the Spotlight—an initiative that includes animals considered most at risk for extinction and prioritizes their recovery efforts. The black abalone is also listed as endangered under the ESA.

NOAA Fisheries is dedicated to conserving and restoring white abalone. Our scientists use innovative techniques to study, protect, and restore their population. We also work with our partners to ensure that regulations and management plans are in place to reduce poaching and increase the wild abalone population.

Population Status

Commercial fishing has severely reduced white abalone numbers from historical levels. Surveys in southern California show a 99 percent decrease in the number of white abalone since the 1970s. While there were once millions, the current population is likely less than one percent of historical numbers. One well-studied population of white abalone in southern California decreased by about 78 percent between 2002 and 2010 (from about 15,000 individuals to just 3,000).

California’s closure of the white abalone fishery in 1997 may have slowed the species’ decline, but likely not by enough to recover the population. The species now faces threats from low breeding rates and disease. For example, if that well-studied population in southern California is left alone, it will likely continue to decrease by about 10 percent per year.

But, while white abalone are close to extinction, efforts to breed them in captivity and reintroduce them to the wild could help the species recover.

Appearance

White abalone have a thin, oval-shaped shell. The shell has a row of respiratory pores (holes) used to breathe, remove waste, and release gametes. The bottom of its foot—the muscle it uses to move and adhere to rocks—is orange in adult animals. It also has a mottled tan-orange epipodium, an extension of the foot with tentacles used to sense the surrounding environment.

Behavior and Diet

Abalone are slow-moving bottom dwellers. They adhere to rocks and other hard surfaces using their muscular foot and when disturbed they become difficult or impossible to remove. An abalone can also use its foot to move across surfaces.

Adults eat different types of algae. They can catch kelp drifting along the seabed or eat kelp still attached to rocks. The reddish-brown color of their shells shows that white abalone eat some types of red algae throughout their lives.

Where They Live

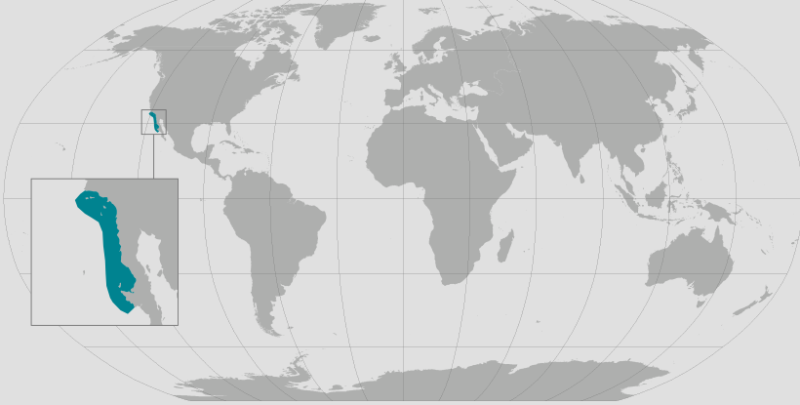

White abalone live on low-relief rocky substrates, typically alongside sand channels, which tend to accumulate the algae they eat. They are usually found at depths of 50 to 180 feet, making them the deepest living abalone species. Historically, white abalone were found in the Pacific Ocean from Point Conception, California, to Punta Abreojos, Baja California, in Mexico. In California, they were most abundant at offshore islands (especially San Clemente and Santa Catalina Islands) and submerged banks (primarily Tanner and Cortes Banks). At the southern end of the range in Baja California, white abalone were often reported along the mainland coast, but were also found at many islands, including Isla Cedros, Isla Natividad, and Isla Guadalupe. Today, researchers have found extremely low numbers of white abalone along the mainland coast of southern California, and at a few of the offshore islands and banks. The status of the species in Mexico remains largely unknown. While there is little or no recent information from Baja California, commercial fishery data suggest that the population there is also depleted.

World map providing approximate representation of the white abalone's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the white abalone's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

White abalone live about 35 to 40 years. Adults become sexually mature in the wild when they are four to six years old.

Abalone reproduce by broadcast spawning—releasing their eggs and sperm into the water. This means fertilization succeeds more often when groups of adult male and female abalone are close to each other when they spawn. Fertilized eggs hatch into swimming larvae, which settle to benthic habitats after ~7 days where theygrow into juveniles and adults.

Threats

Overfishing

Due to their need to be near others to successfully reproduce, white abalone can be depleted by intense fishing that targets groups of animals.

Commercial and recreational harvest of white abalone in California peaked in the 1970s, decreased in the late 1970s to early 1980s, and closed in 1997. The fishery used size limits and seasons to reduce the number of abalone caught. Even with these protections, the fishery greatly decreased the abalone populations and has had long-term effects on their recovery.

Low Reproduction Rates

The most significant threat to white abalone recovery is low reproduction rates.

One adult female abalone can release over 10 million eggs at a time—but unless the eggs come in contact with sperm from spawning males, they cannot be fertilized. With their low population numbers, abalone are often found alone, without potential mates nearby. This makes spawning in the wild unlikely or impossible.

Wild abalone have produced few offspring since the late 1960s/early 1970s. Studies have found that abalone mortality exceeds reproduction in the wild. In a review of the status of white abalone in 2000, scientists estimated that the remaining wild white abalone would disappear without help from humans.

Disease

Abalone are also threatened by disease. Withering syndrome, one common type of infection, is a fatal disease that affects the digestive organs of abalone. The pathogen that causes it is currently present in the coastal oceans of southern California. No wild white abalone have been found to have the fatal symptoms of withering syndrome, but captive abalone have died from the disease and wild white abalone are known to carry the pathogen that causes it. Although disease was not a threat to abalone in the past, withering syndrome now threatens the recovery of this species.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | Phylum | Mollusca | Class | Gastropoda | Order | Archaeogastropoda | Family | Haliotidae | Genus | Haliotis | Species | sorenseni |

|---|

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/11/2025

What We Do

Conservation & Management

We are committed to protecting and rebuilding the white abalone population through conservation and recovery measures, taken in close partnership with several other organizations. Our work includes:

- A captive breeding and outplanting program to reintroduce abalone into the wild

- Monitoring the small wild population of white abalone using SCUBA and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs)

- Monitoring and characterizing the habitats that remnant wild populations of white abalone use

Science

We study the biology, behavior, and ecology of the white abalone. The results of our research inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this critically endangered species. Our work includes:

- Surveying potential white abalone habitats

- Developing new captive breeding techniques

- Outplanting juvenile captive-bred white abalone to establish and enhance wild populations

How You Can Help

Know the Law

It is illegal to fish for, catch, or keep any species of abalone in California except recreational take of red abalone north of San Francisco during designated periods.

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

Red abalone grown at The Cultured Abalone Farm in Santa Barbara, California. Credit: The Cultured Abalone Farm

Red abalone grown at The Cultured Abalone Farm in Santa Barbara, California. Credit: The Cultured Abalone Farm

Veteran Colton Long monitors salmon and steelhead habitat in California’s Klamath River basin. Credit: NOAA Fisheries.

Veteran Colton Long monitors salmon and steelhead habitat in California’s Klamath River basin. Credit: NOAA Fisheries.

Southern Resident killer whale swimming with calf. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Southern Resident killer whale swimming with calf. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Recommended 2024 Species Recovery Grants Projects

The small red shell is a juvenile white abalone on the inside edge of an adult abalone shell. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

The small red shell is a juvenile white abalone on the inside edge of an adult abalone shell. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Rare Juvenile White Abalone Spotted Off California Raises Hope for Endangered Shellfish

In the Spotlight

White Abalone

White abalone are plant-eating marine gastropods (similar to snails and slugs) that live on rocky parts of the sea floor. Of the seven species of abalone that occur off the West Coast of North America, white abalone are the closest to extinction.

White abalone were once plentiful along the coasts of southern California and Baja California, Mexico, but the population has declined rapidly. This decline was largely due to the operation of a brief, but intense commercial fishery in southern California prior to the 1980s. All abalone fisheries have been closed since 1997, but unfortunately the white abalone populations have not recovered as expected.

NOAA Fisheries listed white abalone as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 2001. The rapid decline and dire status of the white abalone population makes it a priority for focusing efforts within NOAA Fisheries and with our partners to stabilize and prevent the extinction of this unique species.

Species Recovery

To aid the recovery of white abalone, NOAA Fisheries formed a team of scientists and stakeholders to assist with developing a white abalone recovery plan which was finalized in October 2008. Development of the plan relied upon scientific studies and other sources of information to establish specific criteria that would indicate the recovery of these animals.

Species in the Spotlight Priority Actions

We developed a Species in the Spotlight 2021–2025 Priority Action Plan for white abalone that builds on the recovery plan and the 2016–2020 Priority Action Plan. The plan lists key actions NOAA Fisheries and its partners can take to help recover the species. These actions include:

- Improve reproductive output and maximize survival of captive-bred animals.

- Expand conservation aquaculture capacity to reach production goal of 10,000 to 25,000 juveniles for outplanting per year through 2025.

- Expand outplanting and monitoring programs in the wild.

- Develop a shared database for recovery partners.

- Develop a comprehensive, multi-institution outreach approach.

In our first five years of the Species in the Spotlight initiative, we have:

- Expanded partnerships to support the captive breeding program.

- Increased captive production by several orders of magnitude—from thousands to millions over the last two years.

- Implemented the first experimental outplant of juvenile white abalone to the wild—release of approximately 4,200 juveniles.

- Developed a plan to continue outplanting approximately 9,600 abalone per year through 2024, for a total of more than 51,000.

- Expanded research and outreach partnerships with Mexico.

- Refined and expanded habitat monitoring to identify future outplanting sites.

These actions will help NOAA Fisheries, other federal and state resource agencies, environmental organizations, and other partners to stop the decline of white abalone and promote their recovery.

Watch scientists outplanting captive-bred white abalone in their native waters of Southern California:

2017 Species in the Spotlight Hero Award

Dr. Kristin Aquilino has played an instrumental role in shaping the captive breeding program for white abalone. Kristin managed the program—charged with rebuilding the declining populations of wild abalone—at the University of California, Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory.

Learn more about Kristin's work

2019 Partner in the Spotlight Award

Amanda Bird, founder of the Paua Marine Research Group, has played an instrumental role in advancing field-based methods to restore white abalone populations in the wild throughout the Southern California Bight. In 2013, as part of her Master's program at California State University, Fullerton, Amanda focused on assessing the population status of Southern California pinto abalone. Pinto abalone are closely related to white abalone. During her thesis research, Amanda worked closely with NOAA Fisheries on white abalone recovery efforts.

Learn more about Amanda's work

2021 Partner in the Spotlight Award

Jim Moore, Laura Rogers-Bennett, and Ian Taniguchi (California Department of Fish and Wildlife) have each devoted their long and illustrious careers advancing our understanding of abalone health, ecology, and conservation. Dr. Jim Moore developed several disease treatment and health maintenance protocols that improve the likelihood that our captive abalone will be healthy when they return to the ocean. Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett was instrumental in establishing the state-of-the-art captive breeding program at the University of California, Davis - Bodega Marine Laboratory. Mr. Ian Taniguchi has played a key role in collecting broodstock for our captive breeding program, monitoring outplanted white abalone, and designing and deploying abalone outplanting modules that keep abalone safe while they acclimate to their natural environment.

Learn more about Jim, Laura, and Ian’s work

2023 Partner in the Spotlight Award

The Bay Foundation (TBF), led by Chief Executive Officer Tom Ford, has been partnering with NOAA on kelp and abalone restoration for nearly two decades in the Southern California Bight. TBF has made major contributions to the white abalone recovery program from 2021-2022. During the pandemic, they were able to establish safe protocols for continued field and laboratory operations in a timely manner. TBF staff transported, cared for, tagged, fed, and prepared thousands of white abalone in a well-maintained laboratory environment during the months preceding outplanting to native habitats. Their dive teams have proven indispensable for monitoring abalone habitat and populations. For all of these reasons and more, TBF is the recipient of the Partner in the Spotlight award in 2023.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/11/2025

Management Overview

White abalone are protected under the Endangered Species Act. NOAA Fisheries has dedicated significant resources to monitoring and rebuilding their populations. We have developed a captive breeding program and routinely monitor the status and habitats of wild abalone in California.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Action

The ESA requires NOAA Fisheries to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. Our plan for white abalone seeks to help them thrive, allowing them to be reclassified from “endangered” to “threatened” and ultimately removed from the list of protected species.

The plan recommends five major actions:

- Monitor populations and their habitat in the wild

- Protect populations and their habitat in the wild

- Use a captive breeding program to enhance wild populations

- Develop an enforcement, public outreach, and education plan

- Get financial support for white abalone recovery

Read the recovery plan for white abalone

Implementation

Together with our partners, we undertake many activities to support the goals of the white abalone plan. The goal is to increase the wild white abalone populations in California and Mexico to self-sustaining levels.

Efforts to conserve white abalone include:

- A captive breeding program

- Pilot outplanting to establish and enhance wild populations

- Monitoring the wild population and its habitat use

- Public outreach and education

Conservation Efforts

Captive Breeding Program

NOAA Fisheries and its partners have developed a captive breeding program to produce young abalone that can be reintroduced into the wild, in hopes to protect white abalone from extinction. Our West Coast Region coordinates the captive breeding program in close partnership with the University of California at Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory and in partnership with several other facilities throughout California.

Once the captive-bred abalone are old enough, researchers will release them into the wild. These captive-bred abalone will grow and become a part of the remaining wild population, where they will hopefully improve the spawning success and be incorporated into healthy, self-sustaining populations.

The Bodega Marine Laboratory oversees the captive breeding program. The program’s first successful spawning attempt in more than a decade occurred in 2012 at the Aquarium of the Pacific and at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The program has successfully raised white abalone and increased the number of individuals raised in captivity each year since 2012.

Captive breeding efforts by current and future partners are expected to produce hundreds of thousands of animals that are ready to be reintroduced to the wild over the next 5 to 15 years. NOAA Fisheries is working closely with its partners to reduce disease risks for captive-bred abalone and to develop tools for increasing the survival of captive-bred abalone once reintroduced to the wild.

Learn more about stock enhancement and captive breeding programs

Outplanting Program

NOAA Fisheries and its partners have begun experimental outplanting of white abalone to the wild. In November 2019, captive-bred juvenile white abalone were released for the first time into coastal waters off southern California. Since then, additional juveniles have been outplanted and monitored to assess their survival, movements, and growth over time. The lessons learned from these experimental outplantings will guide future, large-scale efforts to restore white abalone and bring this species back from the brink of extinction.

Learn more about experimental outplanting efforts

Monitoring the Wild Population

We work with our partners to monitor wild white abalone habitats and track population trends over time in southern California. These surveys help us assess the recovery of wild white abalone populations and will help us determine whether our captive breeding program is working.

We monitor the distribution, abundance, and behavior of white abalone using remotely-operated vehicles (ROVs), SCUBA, acoustic telemetry, and time lapse cameras. We steadily improve our methods for surveying populations and studying their movements, and are developing genetic techniques to track individual animals. We are also helping abalone health specialists monitor for the pathogen that causes withering syndrome in southern California waters and study the risks that healthy abalone face when they come in contact with the pathogen.

Continuing and expanding our monitoring program will help the species by:

- Providing data needed to measure long-term population trends.

- Finding signs of disease so that we can avoid mortality in the captive breeding program.

- Developing tools to identify white abalone in the wild and determine whether they are captive-bred or wild-bred.

- Understanding factors that affect white abalone survival, growth, and reproduction.

- Synthesize available information to improve abalone conservation efforts.

Learn more about our population monitoring work

Public Outreach and Education

NOAA provided funding and guidance to create an interactive exhibit about white abalone at the Aquarium of the Pacific. We also supported "Get Inspired," a local non-profit organization, in creating a classroom abalone program and curriculum. Many high school classrooms in Orange County, California currently culture abalone through this program.

Regulatory History

Commercial fisheries severely reduced white abalone numbers from historical levels. The state of California closed the white abalone fishery in 1996, then closed all abalone fisheries in central and southern California in 1997. The same year, we designated the white abalone as a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act from central California to Baja California, Mexico. After completing a comprehensive status review of the species, we listed white abalone as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act in 2001. We assessed but did not designate critical habitat to protect the location of remaining wild white abalone populations.

NOAA Fisheries published the White Abalone Recovery Plan in 2008 to identify actions that would protect the species. In addition, we have taken steps to rebuild the population including:

- Development of a captive breeding program to reintroduce white abalone into the wild

- Release of captive-bred white abalone into the wild to establish and enhance populations

- Monitoring wild abalone populations and their habitat use

In 2016, NOAA Fisheries developed a five-year action plan to build on the existing recovery plan. NOAA Fisheries developed an updated five-year action plan for 2021–2025.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/11/2025

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the white abalone. The results are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this species.

Along with NOAA Fisheries, many groups—both in the United States and in other countries—are working to help save the white abalone. Among them are Channel Islands National Park, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and El Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE; Baja California, Mexico).

White Abalone Restoration Consortium

The White Abalone Restoration Consortium is made up of many groups, all working towards expanding scientific knowledge of white abalone and increasing public awareness. Scientists, fishermen, conservation organizations, universities, federal and state agencies, and private organizations are working together to:

- Locate white abalone in the wild by surveying their natural habitat.

- Collect abalone from the wild to support a captive breeding program.

- Breed and raise new generations of young abalone.

- Enhance populations of white abalone that can reproduce on their own in the wild.

Habitat Surveys

Our scientists are working to learn more about which habitats are best suited to white abalone. We use remotely operated vehicles, SCUBA, seabed-mapping sonars, and computer models to study abalone habitats in great detail. Those details let us narrow down the wide variety of habitat features important to white abalone. We also collect information on general habitat features like depth and algal types, which could help predict the presence of white abalone in unexplored areas. These surveys help ensure that conservation efforts focus on areas most likely to support healthy white abalone populations.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/11/2025

Documents

Recovering Threatened and Endangered Species Report to Congress (FY 2021-2022)

This Report to Congress summarizes efforts to recover all transnational and domestic species under…

Species in the Spotlight: Priority Actions 2021–2025, White Abalone

The Species in the Spotlight initiative is a concerted agency-wide effort to spotlight and save…

Endangered Species Act 5-year Status Review of White Abalone (Haliotis sorenseni)

The summary and evaluation of progress to date on recovery implementation of White abalone

Species in the Spotlight: Priority Actions 2016–2020, White Abalone

In 2015, NOAA Fisheries announced a new program to focus and redouble our efforts to protect eight…

Data & Maps

Recovery Action Database

Tracks the implementation of recovery actions from Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans.

Research

Abalone Research in the Southwest

This research focuses on our local abalone species to develop methods to support and expand commercial aquaculture in the region as well as aid in restoration programs for federally endangered black and white abalone.

Experimental Aquarium at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center

The aquarium at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center facilitates research across many species, including the endangered black and white abalone.

Genetics, Physiology and Aquaculture in the Pacific

We conduct research across multiple focal areas and species through genetic and physiological tools to provide improved data products for managers and industry.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 09/11/2025